Info-Dumping in Science Fiction & Fantasy Novels by Breyonna Jordan

Info-dumping occurs when writers provide excessive background information in a single section, potentially overwhelming readers and disrupting the narrative flow. This issue is prevalent in science fiction and fantasy genres due to their complex world-building requirements. Indicators of info-dumping include lengthy paragraphs, minimal action or conflict, and the author's voice overshadowing the characters'. To avoid this, authors should focus on essential details, integrating additional information gradually as the story progresses. This approach keeps readers engaged without inundating them with information, maintaining a robust and immersive setting.

This blog post was written by a human.Hi readers and writerly friends!

If you’re new to the blog, thanks for stopping by, and if you’re a returning reader, it’s nice to see you again! For this post, Breyonna Jordan is taking over the blog to tell you all about info-dumping in science-fiction and fantasy novels! Leave her a comment and check out her website and other socials!

Breyonna Jordan loves exploring new frontiers—underground cities, mythical kingdoms, and expansive space stations, to be exact. As a developmental editor, she relishes every opportunity to help world-builders improve their works and learn more about the wonderful world of writing. She enjoys novels that are fresh, far-reaching, and fun and she can’t wait to see your next book on her TBR list.

Breyonna Jordan is a developmental editor who specializes in science-fiction and fantasy.

What is Info-Dumping?

When writing sci-fi or fantasy, there’s a steep curve on how much the audience needs to know—a world of a curve in fact.

You may have pages and pages of elaborate world histories that readers must be filled in on—the current and past ruling monarchs, failed (or successful) uprisings, how natural resources became so scarce in this particular region, or why a military state exists in this country, but not in the surrounding lands.

Alternatively, you may feel the need to include pages of small details concerning the settings and characters your readers are exploring. While it’s important to include specific details in your writing—the reader can’t possibly know that the night sky features four moons unless you convey these details—oftentimes, the excess exposition can be overwhelming to readers.

This info-dumping can be a pervasive problem in fiction, maybe even the problem that stops you from finding an awesome agent or from obtaining a following on Amazon.

So, below I’ve offered some tips for spotting info-dumping, reasons for and the potential consequences of info-dumping, as well as several tips for avoiding the info-dump.

How Do You Identify Info-Dumping In Your Manuscript?

A section of your work may contain info-dumping if you find:

you are skipping lines while reading (Brotzel 2020),

the paragraphs are very long,

there is little action and conflict occurring,

your voice (and not your characters) has slipped in,

that it looks like it was copied directly from your outline

To help you get a better idea of what excessive exposition can look like, here are two examples of info-dumping from the first chapter of a sci-fantasy manuscript I worked on:

“Hawk was guarding the entrance to the cave while Beetle went for the treasure. These were not their real names of course but code-names given to them by their commander (now deceased) to hide their true identities from commoners who may begin asking questions. Very few people in the world knew their true names and survived to speak it. Hawk and Beetle knew each other’s true names but had sworn to secrecy. They were the youngest people on their team. Beetle was seventeen with silver hair and had a talent for tracking. Hawk was twenty-one with brown hair which he usually wore under a white bandana. He was well-mannered and apart from his occupation in burglary was an honest rule-follower. Beetle and Hawk had known each other since they were children and were as close as brothers.”

“It is one of the greatest treasures in the entire world of Forest #7. This was thought only to have existed in legend and theological transcripts. This Staff was powered by the Life Twig, a mystic and ancient amulet said to contain the soul of Wind Witch, a witch of light with limitless powers.”

Why Do Writers Info-Dump and What Impacts Does It Have On Their Manuscripts?

As a developmental editor who works primarily with sci-fi and fantasy writers, I’ve seen that info-dumping can be especially difficult for these authors to avoid because their stories often require a lot of background knowledge and world-building to make sense.

In space operas, for example, there may be multiple species and planetary empires with complex histories to keep track of. In expansive epic fantasies, multiple POV characters may share the stage, each with their own unique backstory, tone, and voice.

Here are some other reasons why world-builders info-dump:

they have too many characters, preventing them from successfully integrating various traits,

they want to emphasize character backstories as a driver of motivation,

their piece lacks conflict or plot, using exposition to fill up pages instead,

they are unsure of the readers ability to understand character goals, motivations, or actions without further explanation,

they want to share information that they’ve researched (Brotzel 2020),

they want readers to be able to visualize their worlds the way they see them

A Hobbit house with wood stacked out front. Photo by Jeff Finley.

Though these are important considerations, info-dumping often does more harm than good. Most readers don’t want to learn about characters and settings via pages of exposition and backstory. Likewise, lengthy descriptions:

distract readers from story and theme,

encourage the use of irrelevant details,

make your writing more confusing by hiding key details,

decrease dramatic tension by boring the reader,

slow the pacing and immediacy of writing,

prevent you from learning to masterfully handle characterization and description

Think back to the examples listed above. Can you see how info-dumping can slow the pace from a sprint to a crawl? Can you spot all the irrelevant details that detract from the reader's experience? Do you see the impact of info-dumping on the author’s ability to effectively characterize and immerse the reader in the scene?

Info-dumping is a significant issue in many manuscripts. Often, it’s what divides the first drafts from fifth drafts, a larger audience from a smaller one, a published piece from the slush pile.

What Techniques Can Be Used to Mitigate Info-Dumping?

That said, below are three practical tips to help you avoid and resolve info-dumping in your science-fiction and fantasy works:

Keep focus on the most important details. You can incorporate further information as the story develops. This will allow readers to remain engrossed in your world without overwhelming them. It will also help you maintain a robust setting in which there’s something new for readers to explore each time the character visits.

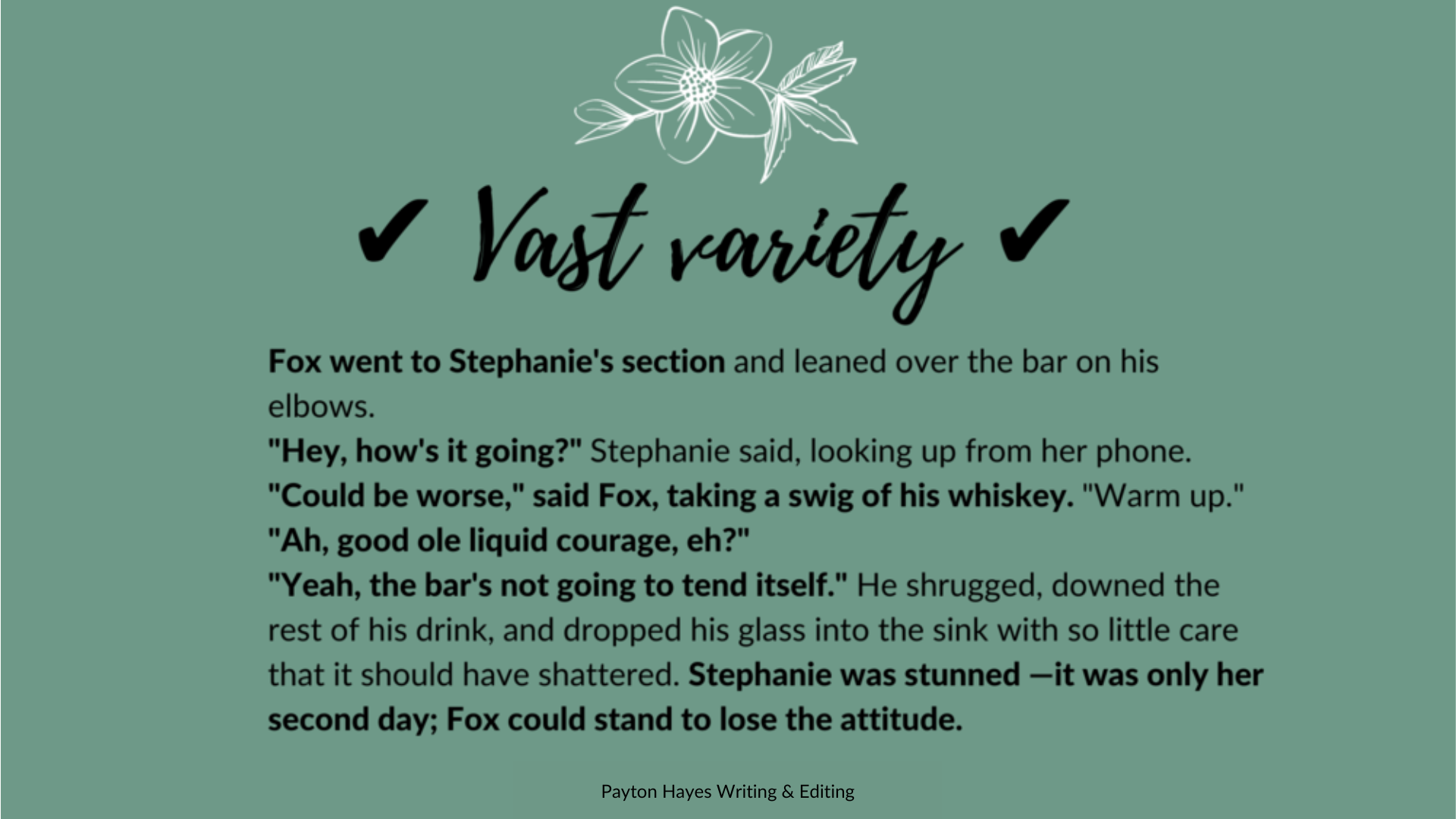

Weave details between conflict, action, and dialogue (Miller 2014). This will allow the reader to absorb knowledge about your world without losing interest or becoming confused. An expansive galactic battle presents the perfect opportunity to deftly note the tensions between races via character dialogue and behavior. A sword fighting lesson can easily showcase new technology (Dune anyone?). A conversation about floral arrangements for a wedding can subtlysubtely convey exposition. Just make sure to keep the dialogue conversational and realistic.

Allow the reader to be confused sometimes. Most sci-fi and fantasy readers expect to be a bit perplexed by new worlds in the earliest chapters. They understand that they don’t know anything, and thus expect not to learn everything at once. Try not to worry too much about scaring them off with new vocabulary and settings. They can pick up on context clues and make inferences as the story progresses. handle it. If you’re still concerned about the amount of invented terminology and definitions, consider adding a glossary to the back matter of the book instead.

Of course, this all raises the question…

Is It Ever Okay to Info-Dump?

You might think to yourself, “I want to stop info-dumping, but it’s so difficult to write my novel without having to backtrack constantly to introduce why this policy exists, or why this seemingly obvious solution won’t end the Faerie-Werewolf War.”

If you’re a discovery writer, it might be downright impossible to keep track of all these details without directly conveying them in text which is why I encourage you to do exactly that.

Dump all of your histories into the novel without restraint. Pause a climactic scene to spend pages exploring why starving miners can’t eat forest fruit or how this life-saving magical ritual was lost due to debauchery in the forbidden library halls.

Write it all down…

Foggy woods illuminated by a soft, warm light. Photo by Johannes Plenio.

But be prepared to edit it down in the second, third, or even fourth drafts.

Important information may belong in your manuscript, but info-dumps should be weeded out of your final draft as much as possible.

Additionally, as I mention often, I am a firm disbeliever in the power and existence of writing rules. There are novels I love that use info-dumping liberally and even intentionally (re: Hitchhiker’s Guide to The Galaxy by Douglas Adams). Most classics use exposition heavily as well and they remain beloved by fans old and new.

However, what works for one author may not work for everyone and modern trends in reader/ publisher-preference regard info-dumping as problematic. Heavy reliance on exposition is also connected to other developmental problems, such as low dramatic tension and poor characterization.

If you are intentional about incorporating large swaths of exposition and it presents a meaningful contribution to your work, then info-dumping might be a risk worth taking. If the decision comes down to an inability to deal with description and backstory in other ways then consider reaching out to an editor or writing group instead.

What are some techniques you’ve used to avoid info-dumping in your story? Let us know in the comments!

Bibliography

Brotzel, Dan. “Get On With It! How To Avoid Info Dumps in Your Fiction.” Medium article, February 12, 2020.Finley, Jeff. “Hobbit House.” Unsplash photo, February 28, 2018.Gililand, Stein Egil. “Beautiful Green Northern Lights in the Sky.” Pexels photo, January 7, 2014 (Thumnail photo).Miller, Kevin.“How to Avoid the Dreaded Infodump.” Book Editing Associates article, April 14, 2014.Plenio, Johannes. “Forest Light.” Unsplash photo, February 13, 2018.

Related Topics

Book Writing 101: How To Come Up With Great Book Ideas And What To Do With ThemBook Writing 101: How To Write A Book (The Basics)Book Writing 101: Starting Your Book In The Right PlaceBook Writing 101: How To Choose The Right POV For Your NovelBook Writing 101: How To Achieve Good Story PacingBook Writing 101: How To Name Your Book CharactersBook Writing 101: How to Develop and Write Compelling, Consistent CharactersBook Writing 101: Everything You Need To Know About DialogueHow To Write Romance: Effective & Believable Love TrianglesHow To Write Romance: Enemies-To-Lovers Romance (That’s Satisfying and Realistic)How To Write Romance: 10 Heart-Warming and Heart-Wrenching Scenes for Your Romantic ThrillerHow To Write Romance: Believable Best Friends-To-LoversHow To Write Romance: The Perfect Meet CuteCheck out my other Book Writing 101 and How To Write Romance posts.Book Marketing 101: Everything Writers Need To Know About Literary Agents and QueryingHow To Submit Your Writing To—And Get It Published In—Literary Journals

Recent Blog Posts

Book Writing 101: Everything You Need To Know About Dialogue

No matter what genre you write in, learning how to write dialogue effective is an essential part of any writer’s toolkit. Poorly-written dialogue can be distracting or worse —it could cause your readers to close the book in disgust. However, dialogue that is done well can transform your characters into truly believable people and you readers into satisfied, lifelong fans. Of course, the best kind of dialogue isn’t just believable conversation between characters. Good dialogue provide exposition, involves distinct language true to the voice of the speaker, and most importantly, helps move the story along. Dialogue is directly tied to pacing, plot, and tension, and can make or break your story just as much as lame characters or a sagging plot.

This guide is separated into three parts for your convenience — Dialogue Basics, Punctuating Dialogue, and Dialogue Tags —and is filled with cheat sheets, quick-reference-guides, examples, and more to help you with your writing!

This blog post was written by a human.Hi Readers and writerly friends!

This week in Freelancing, we’re discussing dialogue tags and how to properly format them. Consider this as your new intensive, all-encompassing guide for doing fictional dialogue well.

No matter what genre you write in, learning how to write dialogue effective is an essential part of any writer’s toolkit. Poorly-written dialogue can be distracting or worse —it could cause your readers to close the book in disgust. However, dialogue that is done well can transform your characters into truly believable people and you readers into satisfied, lifelong fans. Of course, the best kind of dialogue isn’t just believable conversation between characters. Good dialogue provide exposition, involves distinct language true to the voice of the speaker, and most importantly, helps move the story along. Dialogue is directly tied to pacing, plot, and tension, and can make or break your story just as much as lame characters or a sagging plot.

This guide is separated into three parts for your convenience: 1) Dialogue Basics, 2) Punctuating Dialogue, and 3) Dialogue Tags—and is filled with cheat sheets, quick-reference-guides, examples, and more to help you with your writing! (This post took me a long time to write, so if you found it helpful, please consider leaving a comment and sharing this with your writerly friends!)

Of course, this is just my own experience as well as examples of other writers who have done dialogue well, but this is by no means a rulebook for dialogue. I’m simply a proponent of the idea that if you know the rules of the writing world well, you can effectively break them well.

Dialogue Basics

Enter late, leave early.

If you’ve been around the writing world for a moment, you might have heard this phrase tossed about when discussing scenes, pacing, and dialogue. It’s a helpful saying for remembering to start a scene at just the right time instead of too early or too late.

Alfred Hitchcock once said that “drama is life with all the boring bits cut out.” Hinging on that, you could say that good dialogue is like a real conversation without all the fluff, and one of the best/easiest ways to cut out that boring fluff is to enter the conversation as late as possible.

Think about it: How many times have you heard someone in real life or in media say, “I hate small talk.” It is the same for your readers. They don’t want to be there for every single “Hi, how are you doing today?” or “I’m doing great, how are you? Thanks for asking. The weather is lovely, isn’t it?” This is a fine and good, but its not interesting dialogue, and it’s highly unlikely that this would move any story’s plot along in a meaningful way. The same goes for other kinds of small talk that usually occurs at the beginning and end of a scene. In order to avoid this kind of slow-paced dialogue, simply enter late and leave early.

Keep dialogue tags simple.

Dialogue tags are the phrases in writing that indicate who is speaking at any given time. “I want to write a book” Layla said. In this case, “I want to write a book” is the dialogue and “Layla said” is the tag. Of course, there are plenty of other dialogue tags you could use besides “said,” such as “stated,” “exclaimed,” or “declared” and so on. When writing dialogue, you generally should keep these elaborate tags to a minimum. Think of it this way, to the reader “said” is boring and simple, but its virtually invisible. Readers expect you to use “said” and because of this, it isn’t distracting to the reader.

Remember the KISS method —Keep It Simple, Sweetie? Remember that for dialogue tags. It’s always better to air on the side of caution than risk potentially distracting your reader with overly complicated, elaborate or convoluted dialogue tags.

As American novelist and screenwriter Elmore Leonard put it:

“Never use a verb other than ‘said’ to carry dialogue. The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in. But ‘said’ is far less intrusive than ‘grumbled,’ ‘gasped,’ ‘cautioned,’ ‘lied’” (Leonard 2021).

“Intrusive” is the operative word here. You want to bring readers into your scene and make them feel like firsthand observers, like one of the characters in the background, without drawing attention to the fact that they’re reading a book. Wordy dialogue tags are a surefire way to yank your readers out of the immersion of a story and snap them back to reality. When you raid your thesaurus for fancy dialogue tags, you risk taking readers out of the scene for a fleeting display of your verbal virtuosity. This is true for any writing where you use convoluted language where you would be better served using simple language instead. If it serves a purpose to use uncommon or elaborate verbiage, then by all means, do so, but if its just for the sake of using big words, the practice of using “wordy” language is best avoided.

Additionally, in some instances, dialogue tags can be removed altogether. If there are only two or three people present in a conversation, dialogue tags aren’t always necessary to keep track of the speaker, especially if their voices are distinct convey a character’s personality to the reader.

Descriptive action beats are your friend.

Action beats are descriptions of the expressions, movements, or even internal thoughts that accompany the speaker’s words, and are included in the same paragraph as the dialogue to indicate that the person acting is the same person who is speaking. Action beats help illustrate what’s going on in a scene, and can even replace dialogue tags, avoiding the need for a long list of lines ending in “he said,” or “she said.”

Check out the fourth part of this guide for an example of how to use action beats to strengthen and vary your dialogue structure.

Character voices should be distinct.

Another key aspect of writing realistic and engaging dialogue is make each character sound distinctly like “themselves.” This employs the use of a number of different linguistic elements, such as syntax and diction, levels of energy and formality, humor, confidence, and any speech-related quirks (such as stuttering, lisping, or ending every sentence like it’s a question). Some of these elements may change depending on the circumstances of the conversation, and especially when it comes to whom each person is speaking, but no matter what, there should always be an underlying current of personality that helps the reader identify each speaker.

Example: Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice

In the very first piece of dialogue in Pride and Prejudice, readers encounter Mrs and Mr. Bennet, the former of whom is attempting to draw her husband, the latter, into a conversation of neighborhood gossip.

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?”

Mr. Bennet replied that he had not.

“But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.”

Mr. Bennet made no answer.

“Do you not want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife impatiently.

“You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.”

This was invitation enough.

“Why, my dear, you must know, Mrs. Long says that Netherfield is taken by a young man of large fortune from the north of England; that he came down on Monday in a chaise and four to see the place, and was so much delighted with it, that he agreed with Mr. Morris immediately; that he is to take possession before Michaelmas, and some of his servants are to be in the house by the end of next week.” (Austen 2002)

Austen’s dialogue is always witty, subtle, and packed with character and is never simple or convoluted. Readers instantly learn everything they need to know about the dynamic between Mr. and Mrs. Bennet from their first interaction: she’s chatty, and he’s the beleaguered listener who has learned to entertain her idle gossip.

Develop character relationships.

Dialogue is an excellent tool to demonstrate and develop character relationships throughout your story. Good dialogue establishes relationships, but great dialogue adds new, engaging layers of complexity to them.

One of the best ways to ensure your character’s dialogue reflects their personalities and relationships is to practice some dialogue writing exercises. It’s likely that you won’t actually end up using the products of these exercises in your writing, but they’re an easy, low-pressure way to practice developing your characters and their relationships to one another.

For this kind of practice, I’ve found that exercises like “What Did You Say?” are particularly helpful.

Pretend three of your characters have won the lottery. How does each character reveal the big news to their closest friend? Write out their dialogue with unique word choice, tone, and body language in mind.

If the lottery isn’t interesting enough, consider changing things up. Maybe three of your characters have a role to play in a murder investigation. Each one knows a different take on what happened. Lottery or murder investigation aside, developing your character’s relationship will teach you more about your characters themselves, their stories and circumstances, and how to write dialogue that best fits within that framework.

Find similar exercises here.

Developing character relationships alongside and through dialogue is an excellent opportunity to work on both simultaneously. In this exercise, there are a number of characteristics that will affect how each character perceives and delivers the news that they’ve won the lottery (or that they’ve been involved in a murder investigation).

These characteristics might include whether a character:

Is confident and outgoing vs. shy and reserved

Takes things in a lighthearted manner rather than being too serious

Has lofty personal aspirations or doesn’t

Couldn’t care less or wants to help others

Thinks they deserve good things or not

Carefully consider each of your characters and which of these categories they fall into. This should help you determine how they all relate and react to each other in the context of such news.

Show, don’t tell.

We’ve all heard this slice of writing advice, probably more times than we can count, but it’s for good reason. Much like the “enter late, leave early” saying, you’ve probably seen or heard this phrase making rounds throughout the writing world. It’s a sliver of advice that creatives like to use as a buzz phrase in writing communities, but there may be a golden nugget of wisdom to be found in it.

Readers enjoy making inferences based on the clues the author provides, so don’t just lay everything out on the table. This doesn’t mean be cryptic —on the contrary. It basically means you should imply information rather than outright stating it.

Take the dialogue below for example. Even if this is the first instance the reader encounters of Jones and Walker, its easy to deduce that they are police officers who used to work together, that they refer to each other by their last names, and that Jones misses Walker — and possibly wants him to come back, despite Walker’s intentions to stay away.

Hey, Jones. Long time no see.”

“Heh, Yeah, Walker, tell me about it. The precinct isn’t the same without you.”

“Well, you know I had good reason for leaving.”

“I do. But I also thought you might change your mind.”

However, cloaking this information in dialogue is a lot more interesting than the narrator simply saying, “Jones and Walker used to work together on the force. Walker left after a grisly murder case, but now Jones needs his help to solve another.”

Of course, sometimes dialogue is a good vehicle for literally telling — for instance, at the beginning or end of a story, it can be used for exposition or to reveal something dramatic, such as a villain’s scheme. But for the most part, dialogue should show rather than tell in order to keep readers intrigued, constantly trying to figure out what it means.

Bounce quickly back and forth.

When writing dialogue, it’s also important to bounce quicky back and forth between speakers, like in a tennis match. Consider the ping-pong pace of this conversation between an unnamed man and a girl named Jig, from Hemingway's short story, "Hills Like White Elephants".

It might seem simple or obvious, but this rule can be an easy one to forget when one speaker is saying something important. The other person in the conversation still needs to respond. Likewise, a way to effectively break this rule is to intentionally omit the other character’s response altogether if the plot warrants it. Sometimes, leaving the other character shocked proves to be just as effective on the reader.

On the other hand, you don’t want lengthy, convoluted monologues unless its specifically intended and needed to drive the plot forward. Take a close look at your dialogue to ensure there aren’t any long, unbroken blocks of text as these typically indicate lengthy monologues and are easily fixed by inserting questions, comments, and other brief interludes from fellow speakers.

Alternately, you can always break it up using small bits of action and description, or with standard paragraph breaks, if there’s a scene wherein you feel a lengthy monologue is warranted.

Try reading your dialogue out loud.

It can be tricky to spot weak dialogue when reading it on the page or a computer screen, but by reading out loud, we can get a better idea of the quality of our dialogue. Is it sonically true to the characters’ distinct voices? Is it complex and interesting, conveying quirks and personality beyond plot? Does it help drive the plot in a meaningful way or is dialogue being used to fill space? If it is the latter, it should be removed, but more on that next.

For instance, is your dialogue clunky or awkward? Does it make you cringe to hear it read aloud? Do your jokes not quite land? Does one of your characters speak for an unusually long amount of time that you hadn’t noticed before, or does their distinct "voice" sound inconsistent in one scene? All of these problems and more can be addressed by simply reading your dialogue out loud.

Don’t take my word for it, take John Steinbeck’s! He once recommended this very strategy in a letter to actor Robert Wallston: “If you are using dialogue, say it aloud as you write it. Only then will it have the sound of speech.”

Remove unnecessary dialogue.

Dialogue is just one tool in the writer’s toolbox and while it’s a useful and essential storytelling element, you don’t have to keep all of the dialogue you write in your first or second drafts. Pick and choose which techniques best tell your story and present the interior life of your characters. This could mean using a great deal of dialogue in your writing, or it might not. Carefully consider your story and the characters and whether or not it makes sense for them to have dialogue between one another in any given scene. Just because dialogue can be brilliant, doesn’t mean it’s always integral to a scene, so feel free to cut it as needed.

Format and punctuate your dialogue properly.

Proper formatting and punctuation of your dialogue makes your story clear and understandable. Nothing is more distracting or disorienting within a story than poorly formatted or improperly punctuated dialogue —well, except for an excess of wordy dialogue tags instead of “said,” but I digress! Likewise, knowing when to use quotation marks, where to put commas, full stops, question marks, hyphens, and dashes will make your text look polished and professional to agents and publishers.

How to format dialogue:

Indent each new line of dialogue.

Put quotation marks around the speech itself.

Punctuation that affects the speech’s tone goes inside the quotation marks.

If you quote within a quote, use single rather than double quotation marks.

If you break up a line of dialogue with a tag (e.g. “she said”), put a comma after the tag. However, if you put a tag in between two complete sentences, use a period.

Speaking of tags, you don’t always need them, as long as the speaker is implied.

If you start with a tag, capitalize the first word of dialogue.

Avoid these major dialogue mistakes.

Tighten up your pacing and strengthen your dialogue by avoiding these common dialogue issues. Although the differences in some of these examples are subtle word choice, usage frequency, and arrangement play a big part in dialogue delivery. Consider how these small changes can make a big difference in your writing.

Too many dialogue tags

As you might have guessed, the most contradictory advice you can receive and most egregious errors you can make when writing dialogue have to do with dialogue tags. Do use them. Don’t use them. Don’t use “said.” Do use “said.” Do use interesting tags. Don’t use too elaborate tags. How does the lowly writer win?

Consider this: good storytelling is a delicate balance between showing and telling: action and narrative. So, how does one do dialogue well? Craft and maintain a sustainable balance between action and narrative within your story. I can’t tell you when and when not to use elaborate dialogue tags or when to cut tags out altogether, but I can suggest that when you examine your dialogue, keep this idea in mind and consider it when you sense the balance of action and narrative has skewed slightly (or dramatically) to one side or the other.

Constantly repeating “he said,” “she said,” and so on, is boring and repetitive for your readers, as you can see here:

So, keep in mind that you can often omit dialogue tags if you’ve already established the speakers, like so:

One can tell from the action beats, as well as the fact that it’s a two-person back-and-forth conversation, which lines belong to which speaker. Dialogue tags can just distract from the conversation — although if you did want to use them, “said” would still be better than fancy tags like “declared” or “effused.”

Lack of structural variety

Much like the “too many tags” issue is the lack of structural variety that can sometimes arise in dialogue. It’s an issue that most commonly presents itself in narrative but can occur in dialogue as well. Not sure what I’m talking about? Take a look at these sections again:

Now, action beats are great, but here they’re used repeatedly in exactly the same way — first the dialogue, then the beat — which looks odd and unnatural on the page. Indeed, any recurrent structure like this (which also includes putting dialogue tags in the same place every time) should be avoided.

Luckily, it’s easy to rework repetitive structure into something much more lively and organic, just by shifting around some of the action beats and tags:

Another common dialogue mistake is restating the obvious — i.e. information that either the characters themselves or the reader already knows.

For example, say you want to introduce two brothers, so you write the following exchange:

This exchange is clearly awkward and a bit ridiculous, since the characters obviously know how old they are. What’s worse, it insults the reader’s intelligence — even if they didn’t already know that Sherri and Kerri were thirty-five-year-old, twin sisters, they wouldn’t appreciate being spoon-fed like this.

If you wanted to convey the same information in a subtler way, you might write it like:

This makes the dialogue more about Indiana Jones than the brothers’ age, sneaking in the info so readers can figure it out for themselves.

Unrealistic smooth-talking and clichés

In your quests to craft smooth-sounding dialogue, don’t make it flow so smoothly that it sounds fake. Unfortunately, this is a weak point of sounding your dialogue out aloud because even though it may sound good, it may not sound believable. Consider reading dialogue with a friend or critique partner to see if it sounds believable coming from someone else. If it doesn’t sound any better read by your friend, it might be an indicator that your dialogue needs some work. It can also be helpful to record dialogue (with the participants’ permission, of course) and study it for natural speech patterns and phrases. (Feel free to leave out any excess “um”s and “er”s that typically accompany authentic dialogue.) Authentic-sounding written dialogue reflects real life speech.

Likewise, you should steer clear of clichés in your dialogue as much as in the rest of your writing. While it’s certainly true that people sometimes speak in clichés (though this is often tongue-in-cheek), if you find yourself writing the phrase “Are you thinking what I’m thinking?” or “Shut up and kiss me,” you may need a reality check.

For a full roster of dialogue clichés, check out this super-helpful list from Scott Myers.

Disregarding dialogue completely

Finally, the worst mistake you can make when writing dialogue is… well, not writing it in the first place! Circling back to one of the first points made in this guide, dialogue is an integral part of storytelling. It’s an important element in any story, no matter the genre because it provides exposition, indicates, personality, and character relationships, and can even be used to reveal a major plot twist during the climax.

So, what do you think of this guide? I will be adding to it periodically, so make sure to bookmark it and join my newsletter to get notifications when updates go live! Let me know your thoughts in the comments below!

Bibliography

Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice. London: Penguin Books, 2002. Amazon.Du Preez, Priscilla. “sihouette of three people sitting on cliff under foggy weather photo.” Unsplash photo (Thumbnail photo), March 5, 2019.Leonard, Elmore. “Elmore Leonard: 10 Rules Of Writing.” Fs blog post, accessed June 27, 2021.Myers, Scott. “The Definitive List of Cliché Dialogue.” Medium article, March 8, 2012.Reedsy. “A Dialogue Writing Exercise.” Reedsy blog post, accessed June 27, 2021.

Related Topics

Get Your FREE Story Binder Printables e-Book!Book Writing 101: How To Come Up With Great Book Ideas And What To Do With ThemBook Writing 101: How To Write A Book (The Basics)Book Writing 101: Starting Your Book In The Right PlaceBook Writing 101: How To Choose The Right POV For Your NovelBook Writing 101: How To Achieve Good Story PacingBook Writing 101: How To Name Your Book CharactersBook Writing 101: How to Develop and Write Compelling, Consistent CharactersInfo-Dumping in Science Fiction & Fantasy Novels by Breyonna JordanHow To Write Romance: Effective & Believable Love TrianglesHow To Write Romance: Enemies-To-Lovers Romance (That’s Satisfying and Realistic)How To Write Romance: 10 Heart-Warming and Heart-Wrenching Scenes for Your Romantic ThrillerHow To Write Romance: Believable Best Friends-To-LoversHow To Write Romance: The Perfect Meet CuteCheck out my other Book Writing 101 and How To Write Romance blog posts!Check out more of my Author Advice and Writing Advice blog posts!

Recent Blog Posts

Book Writing 101: How To Choose The Right POV For Your Novel

The point of view is the lens through which your readers connect with your characters and having the right POV can make your story while having the wrong point of view can certainly break it. There’s no real wrong or right here, but sometimes certain viewpoints just make sense for certain stories. We’re going to look at the definition of POV, the importance of POV, the four different POV’s, what POV’s are popular in what genres, how to know when the POV you’re using is right/wrong for your novel, the top POV mistakes new writers make, and how to execute POV well so that it acts as the perfect vehicle through which you tell your story.

A stack of books with different points of view. Photo by Payton Hayes.

This blog post was written by a human.Hi readers and writerly friends!

This week in the Freelancing category, we’re discussing how to choose the right Point of View (POV) for your book. This refers to not only the way your story is told but also who is telling your story. The point of view is the lens through which your readers connect with your characters and having the right POV can make your story while having the wrong point of view can certainly break it. There’s no real wrong or right here, but sometimes certain viewpoints just make sense for certain stories. We’re going to look at the definition of POV, the importance of POV, the four different POV’s, what POV’s are popular in what genres, how to know when the POV you’re using is right/wrong for your novel, the top POV mistakes new writers make, and how to execute POV well so that it acts as the perfect vehicle through which you tell your story.

What Is a Point of View or POV?

Point of view is (in fictional writing) the narrator's position in relation to a story being told, or position from which something or someone is observed.

The point of view, or POV, in a story is the narrator’s position in the description of events, and comes from the Latin phrase, “punctum visus,” which literally means point sight. The point of view is where a writer points the sight of the reader.

Note that point of view also has a second definition.

In a discussion, an argument, or nonfiction writing, a point of view is a particular attitude or way of considering a matter. This is not the type of point of view we’re going to focus on in this blog post, (although it is helpful for nonfiction writers, and for more information, I recommend checking out Wikipedia’s neutral point of view policy).

I also enjoy the German word for POV, which is Gesichtpunkt, which can be translated as “face point,” or where your face is pointed. How’s that for a great visual for point of view?

Also, point of view is sometimes called “narrative mode.”

Why is Point of View or POV so important?

So, why does point of view matter so much? Point of view filters everything in your story. Every detail, event, piece of dialogue, person, and setting is observed through some point of view. If you get the point of view wrong, your whole story will suffer for it.

One writing mistake I see often in my editing work is when writers use the wrong point of view for their stories. As the writer, it can sometimes be hard to tell when your story is written in the wrong point of view, but for readers it sticks out like a sore thumb. These mistakes are easily avoidable if you’re aware of them and I’ll go over just how to do that later on in this blog post.

There’s four main POV’s in novel writing

First person point of view. First person is when “I” am telling the story. The character is in the story, relating his or her experiences directly.

Second person point of view. The story is told to “you.” This POV is not common in fiction, but it’s still good to know (this POV is common in nonfiction, such as blog posts like this one).

Third person point of view, limited. The story is about “he” or “she.” This is the most common point of view in commercial fiction. The narrator is outside of the story and relating the experiences of a character.

Third person point of view, omniscient. The story is still about “he” or “she,” but the narrator has full access to the thoughts and experiences of all characters in the story.

First Person POV

In first person point of view, the narrator is in the story and is the one who is telling the events he or she personally experiencing. The easiest way to remember first person, is that the narrative will use first-person pronouns such as My, Me, Myself, and I. First person point of view is one of the most common POVs in fiction writing. What makes this point of view so interesting and challenging, is that all of the events in the story are experienced through the narrator and explained in his or her own unique voice. This means first person narrative is both biased and incomplete, and it should be.

Some things to note about first person point of view:

First Person POV is most common to writing. While it does appear in film and theater, first person point of view is typically used in writing rather than other art mediums. Voiceovers and mockumentary interviews like the ones in The Office, Parks and Recreation, Lizzie McGuire, and Modern Family provide a level of first-person narrative in third person film and television.

First Person POV is limited to one narrator. First person narrators observe the story from a single character’s perspective at a time. They cannot be everywhere at once and thus cannot get all sides of the story. Instead, they are telling their story, not necessarily the story.

First Person POV is inherently biased. In first person novels, the reader almost always sympathizes with a first-person narrator, even if the narrator turns out to be the villain or is an anti-hero with major flaws. Naturally, this is why readers love first person narrative, because it’s imbued with the character’s personality, their unique perspective on the world. If I were recounting a story from my life, my own personal worldview would certainly color that story, whether I was conscious of it or not. First-person narrators should exhibit the same behaviors when telling their stories.

Some novelists use the limitations of first-person narrative to surprise the reader, a technique called unreliable narrator. You’ll notice this kind of narrator being used when you, as the reader or audience, discover that you can’t trust the narrator.

For example, Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl pits two unreliable narrators against one another. Each relates their conflicting version of events, one through typical narration and the other through journal entries. Another example is Rosie Walsh’s Ghosted, where the main narrator conveniently leaves out some key information about herself and her missing lover which could change reader opinion of her, had it been presented earlier in the story. Once it finally is presented, readers can’t help but feel they were deceived by the narrator and wonder who they should trust at the end of the story.

Other Unique Uses of First-Person Narrative:

Harper Lee's novel To Kill a Mockingbird is told from Scout's point of view. However, while Scout in the novel is a child, the story is told from her perspective as an older woman reflecting on her childhood.

The classic novel Heart of Darkness, by Joseph Conrad, is actually a first-person narrative within a first-person narrative. The narrator recounts verbatim the story Charles Marlow tells about his trip up the Congo river while they sit at port in England.

Many first-person novels feature the most important character as the storyteller. However, in novels such as F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby, the narrator is not Jay Gatsby himself but Nick Carroway, a newcomer to West Egg, New York.

"I lived at West Egg, the — well, the less fashionable of the two, though this is a most superficial tag to express the bizarre and not a little sinister contrast between them. My house was at the very tip of the egg, only fifty yards from the Sound, and squeezed between two huge places that rented for twelve or fifteen thousand a season. The one on my right was a colossal affair by any standard — it was a factual imitation of some Hotel de Ville in Normandy, with a tower on one side, spanking new under a thin beard of raw ivy, and a marble swimming pool and more than forty acres of lawn and garden. It was Gatsby's mansion. Or rather, as I didn't know Mr. Gatsby it was a mansion inhabited by a gentleman of that name. My own house was an eye-sore, but it was a small eye-sore and it had been overlooked, so I had a view of the water, a partial view of my neighbor's lawn and the consoling proximity of millionaires — all for eighty dollars a month." (2004, 1)

The 2 major mistakes I often see with First Person POV:

The narrator isn’t likable. Your protagonist doesn’t have to be perfect, and in fact, that’s generally frowned upon because people want to connect with characters and no real human is perfect. They don’t have to be a cliché hero nor do they even have to be good. However, your main protagonist must be interesting. Your audience won’t stick around for even a hundred pages if they have to listen to a character they just don’t enjoy. This is one reason anti-heroes make fantastic first person narrators —they may not be perfect, but they’re almost always interesting.

The narrator tells but does not show. We’ve heard this phrase “show, don’t tell” thrown around a lot in the writing community, and while it’s often used as a buzz phrase, and requires some elaboration to make sense, it’s especially true with first person narration. Don’t spend too much time in your character’s head, explaining what he or she is thinking and how they feel about the situation. The reader’s trust relies on what your narrator does, not what they think about doing. It’s all about action. To build on that, first person is the absolute closest a narrator can get to a reader’s personal experience—by that, I mean readers will make the most connection and feel the most represented by first person narration, as long as it is done correctly. Everything the narrator sees, feels, tastes, touches, smells, hears, and thinks should be as imaginable as possible for your reader. It needs to be the difference between looking at a photo of a field of wildflowers and actually standing in the field (mentally.)

Second Person POV

While not often used in fiction —it is used regularly in nonfiction, web-based content, song lyrics, and even video games — second person POV is good to understand. In this point of view, the narrator relates the experiences using second person pronouns such as “you” and “your.” Thus, you become the protagonist, you carry the plot, and your fate determines the story.

Here are a few great reasons to use second person point of view:

It pulls the reader into the action of the story

It makes the story more personal to the reader

It surprises the reader because second person is not as commonly used in fiction

It improves your skills as a writer

Some novels that use Second Person POV are:

Remember the Choose Your Own Adventure series? If you’ve ever read one of these novels where you get to decide the fate of the character, you’ve read second person narrative.

Similar to the Choose Your Own Adventure series, there was a really interesting and unique interactive game based on Josephine Angelini’s Starcrossed Trilogy that could be played from the Figment website. It was based in Angelini’s modern-day world and surrounded the main character Helen Hamilton, who is gradually revealed to be a modern-day Helen of Troy. The game was a playable maze that took place in Hamilton’s dreams —she would wake up each night after having the same nightmare of being trapped in an endless labyrinth.

The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern takes place primarily in third person but every few chapters, it shifts to second person which pulls the reader right into the story.

The opening of The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern:

ANTICIPATION

The circus arrives without warning.

No announcements precede it, no paper notices on downtown posts and billboards, no mentioned or advertisements in local newspapers. It is simply there, when yesterday it wasn’t.

The towering tents are striped in white and black, no golds and crimsons to be seen. No color at all, save for the neighboring tree and the grass of the surrounding fields. Black-and-white striped and sizes, with and elaborate wrought-iron fence encasing them in a colorless world. Even what little ground is visible from outside is black or white, painted or powdered, or treated with some other circus trick.

But it is not open for business. Not just yet.

Within hours everyone in town has heard about it. By afternoon, the news has spread several towns over. Word of mouth is a more effective method of advertisement than typeset words and exclamation points on paper pamphlets or posters. It is impressive and unusual news, the sudden appearance of a mysterious circus. People marvel at the staggering height of the tallest tents. They stare at the clock that sits just inside the gates that no one can properly describe.

And the black sigh painted in white letters that hangs upon the gates, the one that reads:

Opens at nightfall

Closes at dawn

“What kind of circus is only open at night?” people ask. No one has a proper answer, yet as dusk approaches there is a substantial crowd of spectators gathering outside the gates.

You are amongst them, of course. Your curiosity got the better of you, as curiosity is wont to do. You stand in the fading light, the scarf around your neck pulled up against the chilly evening breeze, waiting to see for yourself exactly what kind of circus only opens once the sun sets.

The ticket booth clearly visible behind the gates is closed and barred. The tents are still, save for when they ripple ever so slightly in the wind. The only movement within the circus is the clock that ticks by the passing minutes, if such a wonder of sculpture can even be called a clock.

The circus looks abandoned and empty. But you think perhaps you can smell caramel wafting through the evening breeze, beneath the crisp scent of the autumn leaves. A subtle sweetness at the edges of the cold.

The sun disappears completely beyond the horizon, and the remaining luminosity shifts from dusk to twilight. The people around you are growing restless from waiting, a sea of shuffling feet, murmuring about abandoning the endeavor in search of someplace warmer to pass the evening. You yourself are debating departing when it happens.

First there is a popping sound. It is barely audible over the wind and conversation. A soft noise like a kettle about to boil for tea. Then comes the light.

All over the tents, small lights begin to flicker, as though the entirety of the circus is covered in particularly bright fireflies, the waiting crowd quiets as it watches this display of illumination. Someone near you gasps. A small child claps his hands with glee at the sight.

When the tents are all aglow, sparkling against the night sky, the sign appears.

Stretched across the top of the gates, hidden in curls of iron, more firefly-like lights flicker to life. The pop as they brighten, some accompanies by a shower of glowing white sparks and a bit of smoke. The people nearest to the gates take a few steps back.

At first, it is only a random pattern of light. But as more of them ignite, it becomes clear that they are aligned in scripted letters. First a C is distinguishable, followed by more letters. A q, oddly, and several e’s. When the final bulb pops alight, and the smoke and sparks dissipate, it is finally legible, this elaborate incandescent sign. Leaning to your left to gain a better view, you see that it reads:

Le Cirque des Rêves

Some in the crowd smile knowingly, while others frown and look questioningly at their neighbors. A child near you tugs on her mother’s sleeve, begging to know what it says.

“The Circus of Dreams,” comes the reply. The girl smiles delightedly.

Then the iron gates shudder and unlock, seemingly by their own volition. They swing outward, inviting the crowd inside.

Now the circus is open.

Now you may enter.

(2012, 3)

There are also many short stories that use second person, and writers such as William Faulkner, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Albert Camus that played with this point of view.

The 2 major mistakes I see when authors write in Second Person POV:

Breaking the fourth wall completely. Some writers, such as Shakespeare often broke the first wall within their writing. However, this must be done correctly, otherwise, it yanks the reader straight out of the story and leaves them feeling distracted and often causes them to cringe at the poorly executed technique. In the plays of William Shakespeare, a character will sometimes turn toward the audience and speak directly to them. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Puck says:

“If we shadows have offended, think but this, and all is mended, that you have but slumbered here while these visions did appear.” —William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Breaking the fourth wall is a technique of speaking directly to the audience or reader (the other three walls being the setting of the story/play.) Another way of looking at it is this: it’s a way the writer can briefly use second person point of view in a first or third person narrative.

Unintentionally alternating between first and second person. This only works if it was done intentionally and makes sense within the context of the story. I am interweaving first and second person in my blog post because I, the writer, am sharing my personal experience with you, the reader. This works and is most common in web-based content, social media or non-fiction, and it can be tricky to pull off in fiction writing.

Third Person POV

In third person point of view, the narrator is outside of the story and is relating the experiences of a character. The central character is not the narrator and in face, the narrator is not present in the story at all. The simplest way to understand third person narration is that it uses third-person pronouns, such as he/she, his/her, they/theirs.

There are two subtypes of third person point of view:

Third Person Omniscient – The narrator has full access to all the thoughts and experiences or all the characters in the story. This subtype of third person narration is not limited by a single viewpoint.

Examples of Third Person Omniscient:

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

The Raven Boys by Maggie Stiefvater

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel (Read my Review Here)

Atonement by Ian McIwan

Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

Atonement is a 2001 British metafiction novel written by Ian McEwan. Set in three time periods, 1935 England, Second World War England and France, and present-day England, it covers an upper-class girl's half-innocent mistake that ruins lives, her adulthood in the shadow of that mistake, and a reflection on the nature of writing. McIwan makes clever use of story order, tense, and third person POV to tell a story from multiple points in time, and due to its nature as a metafiction, the story recognizes itself as a work of fiction that likely could not be achieved in any other point of view.

Metafiction is a form of fiction which emphasizes its own constructedness in a way that continually reminds readers to be aware that they are reading or viewing a fictional work.

Third person limited – the narrator has only some, if any, access to the thoughts and experiences of the character in the story, often just to one character. It is not uncommon for dialogue to be the primary mode of storytelling in this point of view because if the narrator has little to no access to the inner thoughts and feelings of the characters, the reader might not get that information from a third person limited narrator.

Some examples of Third Person Limited POV:

Game of Thrones by George R.R. Martin

Ulysses by James Joyce

1984 by George Orwell

Should you use third person omniscient or third person limited?

The distinction between third person limited and omniscient point of view is unclear and somewhat ineffectual.

Complete omniscience in novels is rate—its almost always limited in one way or another—if not because the human mind isn’t comfortable/capable of handling all of the thoughts and emotions of multiple people at once, then it’s because most writers prefer not to delve that deep into each character anyways.

To determine which subtype of third person point of view you should use in your story, consider this:

How omniscient does your narrator need to be? How deep are you going to go into your character’s minds? How important is it to the story’s pacing, plot, and characterization that you reveal everything and anything they feel or thing at anytime? If its not absolutely necessary, consider leaving some parts out in order to build intrigue in your readers.

The 2 major mistakes I see when authors write in Third Person POV:

Blurring the line between omniscient and limited. This happens all the time because writers don’t fully understand the very, very thin line between the two subtypes. While it can become confusing at times, there certainly is a distinction to be made and you should take great care to ensure you use one or the other in your writing, but not both at once.

Giving readers whiplash by alternating between two characters POV’s too quickly. This happens all too often with omniscient narrators that are perhaps a little too eager to divulge all the character inner workings. When the narrator switches from one character’s thoughts to another’s too quickly, it can jar the reader and break the intimacy with the scene’s main character. Drama requires mystery, intrigue. If the reader knows each character’s emotions, there will be no space for drama.

Woman sitting at a table in the foreground with a man smoking in the background. Photo by cottonbro.

Here’s an example of third person omniscient that is poorly executed:

Meredith wants to go out for the night, but Christopher wants to stay home. He’s had a long day of work and just wants to relax, but she resents him for spending last night out with his friends instead of her.

If the narrator is fully omniscient, do you parse both Meredith’s and Christopher’s emotions during each back and forth?

“I don’t know,” Meredith said with a sigh. “I just thought maybe we could go out tonight.” She resented him for spending the previous evening out with his friends when he had to work yesterday as well. Was it such a crime for her to want to spend time with her partner?

“I’m sorry Mere,” Christopher said, growing tired of the nagging. “I had a long, crappy day at work, and I’m just not in the mood.” Why couldn’t she just let it go? Didn’t she realize how draining his work was? He felt annoyed that she couldn’t step outside of her own view for even a moment.

Going back and forth between multiple characters’ inner thoughts and emotions such as with the example above, can give a reader POV whiplash, especially if this pattern continued over several pages and with more than two characters.

The way many editors and writers get around the tricky-to-master third person omniscient point of view is the show the thoughts and emotions of only one character per scene (or per chapter.)

Some examples of Third Person Omnicient POV done well:

In his epic series, A Song of Ice and Fire, George R.R. Martin, employs the use of “point of view characters,” or characters whom he always has full access to understanding. He will write an entire chapter from their perspective before switching to the next point of view character. For the rest of the cast, he stays out of their heads.

Gillian Shields expertly switches between her characters viewpoints by chapter and by book. In her Immortals series, the first book takes place from the first person POV when told by the main character and switches to third person omniscient when told by the supporting characters. The second book is told the same way. The third book instead is told by one of the supporting characters. The fourth book is told by another, different supporting characters.

Leda C. Muir’s series, the Mooncallers is a fantastic example of excellent execution of third person omniscient point of view as well.

How to choose the right POV for your novel

So, now that we’ve discussed the different types of POV, examples of them executed well, and the top 2 mistakes for each type, let’s discuss how to select the best POV for your story.

Firstly, there’s no best or right point of view. All of these POVs are effective in various types of stories and there are always exceptions to these prescriptive rules. However, it is true that some POVs are often used in certain genres and some are just better suited for certain types of stories and character motifs.

First Person POV: Most often used in YA Fiction in all subgenres, but especially in coming-of-age stories and romance. Often used in Adult romance as well. Romance stories typically alternate between main character and love interest, switching every scene or every chapter.

Second Person POV: Most often used in nonfiction including but not limited to: cookbooks, self-help, motivational books, entrepreneurial, business, or financial books, and interactive narratives such as Choose Your Own Adventure.

Third Person Limited POV: Most often used in all fiction subgenres for all reading levels. This is the fiction go-to. The third person limited POV is fantastic for building tension because the narrators viewpoint is limited.

Third Person Omniscient POV: Most often used in high fantasy or heavy science fiction.

Of course, like I said, there’s always exceptions to the rules. If you know the rules well, then you know how to break them well.

If you’re just starting out with writing, I would suggest using either first person or third person limited point of view because they’re easier to master. However, you can always experiment with different points of view and story tenses and by practicing them, you improve your ability as a writer. Good, prolific writers learn to master different points of view because it opens their writing up to a greater audience and allows more people to feel included in their writing. Of course, we haven’t even discussed inclusivity, works by authors from a marginalized community, or sensitivity writing, but that’s topic for another day. (I’ll probably cover that in this series so keep an eye out for that.)

Whatever you chose, stay consistent.

The number one issue common to all of these different points of view is that new writers often mix them up or unintentionally alternate between multiple viewpoints within one story. As mentioned under the section covering major mistakes with third person omniscient, the other points of view can suffer from unplanned interweave of multiple viewpoints. The main takeaway here is that you should pick one and be consistent. If you do choose to alternate, consider only alternating between a handful of characters and use only third person limited or first person with each one. Whatever point of view choices you make, be consistent.

There are writers who effectively and expertly mix narrative modes because they might have multiple characters who the plot revolves around, but these kinds of switches generally don’t take place until a break in the text occurs, perhaps at a scene or chapter break.

And that’s it for my blog post on the points of view and how to identify and use them! What is your favorite POV to write in? What is your favorite POV to read in? What is your least favorite POV for both of these? What POV do you struggle with most? Let me know in the comments below and don’t forget to check out this week’s writing challenge!

Writing challenge: Your mission this week is to write for fifteen minutes while changing narrative modes as many times as possible. Post your writing practice in the comments and take some time to read the work of other writers here.

Recap: Examples of books that utilize various POVs

Examples of First Person POV:

The Choose Your Own Adventure Series

The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern

The Starcrossed Trilogy by Josephine Angelini

A Midsummer Night’s Dream William Shakespeare

As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner

The Blithedale Romance by Nathaniel Hawthorne

The Stranger and The Fall (dramatic monologue in First Person) by Albert Camus

Examples of Second Person POV:

The Office

Parks and Recreation

Lizzie McGuire

Modern Family

Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Examples of Third Person Omniscient POV:

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

The Raven Boys by Maggie Stiefvater

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel (Read my Review Here)

Atonement by Ian McIwan

Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

A Song of Ice and Fire, George R.R. Martin

The Immortals by Gillian Shields

Mooncallers by Leda C. Muir

Examples of Third Person Limited POV:

Game of Thrones by George R.R. Martin

Ulysses by James Joyce

1984 by George Orwell

Alternating POVs:

A Happy Death by Albert Camus

The Scarlet Letter (mostly in Third Person, with a First Person narrator in the intro) by Nathaniel Hawthorne

Bibliography

Hayes, Payton. "A stack of books with different points of view. " January 15, 2021.Hayes, Payton. "Distance in point of view" (PNG, Graphic) January 15, 2021.Hayes, Payton. "Point of View Pronouns" (PNG, Graphic) January 15, 2021.Cottonbro Studio "Woman sitting at a table in the foreground with a man smoking in the background." Unsplash photo, January 15, 2021 (Thumbnail).Fitzgerald, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby. New York: Scribner, 2004.Morgenstern, Erin. The Night Circus. New York: Anchor Books, 2012.Shakespeare, William. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993 (5.1.440–44).

Related Topics

Book Writing 101: How To Write A Book (Basics)Book Writing 101: Coming Up With Book Ideas And What To Do With ThemBook Writing 101: Starting Your Book In The Right PlaceBook Writing 101: How To Chose The Right POV For Your NovelBook Writing 101: How To Name Your Book CharactersBook Writing 101: How To Achieve Good Story PacingBook Writing 101: How to Develop and Write Compelling, Consistent CharactersStory Binder Printables (Includes Character Sheets, Timelines, World-Building Worksheets and More!)25 Strangely Useful Websites To Use For Research and Novel IdeasPayton’s Picks —40+ of my favorite helpful books on writing and editing.Check out my other Book Writing 101, and Freelancing posts.

Recent Blog Posts

Book Writing 101: How To Achieve Good Story Pacing

In literature, pace, or pacing is the speed at which a story is told—not necessarily the speed at which the story takes place. The pace is determined by the length of the scenes, how fast the action moves, and how quickly the reader is provided with information.

Pacing is an element of storytelling that seems to trip up many new writers. It can be hard to pin down. What is a good pacing for a story? Well, to get a better idea of good story pacing, we have to look at bad story pacing first.

Freytag’s Pyramid from Serious Daring by Lisa Roney. Photo by Payton Hayes.

This blog post was written by a human.Hi readers and writerly friends!

This week in the Freelancing category, we’re continuing the Book Writing 101 series with our third post—how to achieve good story pacing. If you’re looking for the rest of the series, it will be linked at the end of the blog post!

What is pacing?

In literature, pace, or pacing is the speed at which a story is told —not necessarily the speed at which the story takes place. The pace is determined by the length of the scenes, how fast the action moves, and how quickly the reader is provided with information. Story pacing is the momentum of the story and it’s what keeps readers turning pages.

Why does pacing matter in storytelling?

Pacing is an element of storytelling that seems to trip up many new writers. It can be hard to pin down. What is a good pacing for a story? Well, to get a better idea of good story pacing, we have to look at bad story pacing first.

Pacing is also tension. It’s how you build out the rising and falling action of your scenes. When I reference “action” in this blog post, rising and falling action is what I am talking about. This may be literal action scenes, conflict, events, plot points and pinch points, and other peaks and valleys of plot.

If you read my blog post about where to start your novel, then you might remember this next bit. That post (linked at the end of this blog post) is specifically for starting a book, but it serves as a great reminder for starting/ending you scenes and chapters as well.

Pacing is also how you enter and leave scenes and chapters. It’s how you open a scene and keep the momentum all the way through to the “turning point” of that scene or chapter. It’s how you close that scene/chapter and lead into the next one. Think about the “enter late, leave early” rule when trying to achieve goo pacing within your story, and how events in your story drive the plot forward.

What constitutes bad story pacing?

This usually occurs when a story is told at a pace or speed that is either just too fast or too slow for the plot and the events that happen within the story. Story pacing that is just too fast almost gives the reader narrative whiplash in that, everything is being presented so quickly that the reader just can’t seem to keep up and is lost in confusion. Story pacing that is just to slow usually ends up boring the reader and making it hard for him or her to stay motivated to finish the book.

Story pacing really has more to do with the amount of information being presented and the intervals at which it is being presented. Books that have too-fast story pacing often just bombard the reader with information faster than they can process it. For example, a thriller writer may leave things out of the story in an attempt to build intrigue but as the plot progresses, the reader will be come increasingly more confused. In fantasy, too-fast pacing usually arises when the writer drops in a ton of names in rapid succession without really giving the readers time to orient themselves.

However, on the flip side, too-slow pacing can arise in fantasy in much the same way as well. Taking entirely way too long to establish backstory or info-dumping is a great way to slow the story down and bore the reader. And truthfully, this isn’t unique to fantasy; this issue can manifest itself this way in all genres.

Pacing that is too fast: Too much information is presented too often.

Pacing that is too slow: Not enough action is presented often enough.

I know, it looks like I said the same thing twice, only slightly changed—I did.

But in essence, good story pacing is all about balance.

Even seasoned writers struggle to strike the very delicate balance between action and information. What’s worse than a plot twist that comes out of left field? A plot twist that’s more like a straight line than a twist at all. That is to say, the reader could see it coming from a mile away, or due to weak pacing, the world-shattering revelation misses it’s mark and the author’s impact is completely lost on the reader.

Ultimately, to achieve good story pacing is to tell the story in such a way that plot points are reached and key information is revealed at a satisfying and sensible pace.

Identifying pacing issues with word count

This might only be useful if for writers who have critique groups, agents, or editors but essentially, you can identify bad pacing by looking at the word count of a novel. If your editor says “the word count is too low for your genre” then they’re essentially saying, your pacing is too fast, and you’ve not spent enough time building out the story and included too much action. If your editor says “the word count is too high for your genre” then they’re saying your pacing is too slow, and you’ve spent too much time building out the story and not including enough action.

Sentence structure can make or break pacing

Another obvious, concrete clue that your pacing could be off is the way sentences, dialogue, and paragraphs are aesthetically arranged on the page. Think long, drawn-out, convoluted sentences, wordy paragraphs, big, pretentions words, overly-descriptive, adjective-dense, purple pose, a lack of variation in sentence structure, and crowded or skeletal dialogue. These story elements are often easy to overlook, and trying to strike that balance as an afterthought can certainly kill your pacing. Take this paragraph as a meta example. The second sentence commits the very crime that the third sentence calls out.

Think about these things and keep in mind that if it doesn’t add to the writing style, voice, tone or drive the plot, then you don’t need it. Characterization should be dropped in here and there, and not done in page-long descriptions with wordy backstory. Big words and extensive (and often archaic) vocabulary should only be used if it makes sense for the voice, tone, genre, setting, and narrator of the story.

This issue is ubiquitous with academic writing, where some students try to fill their essays with pedantic fluff to reach word count minimums and others just enjoy hearing themselves talk—or reading their own words, rather. Save the filibustering for the Senate.

This doesn’t mean that shorter and more direct sentences are key either. Short, choppy, staccato-like sentences with little variation can undercut tension or mood because they give the reader little time to immerse themselves in description, emotion, or context. Like I said, it’s all about balance. The secret to achieve this balance and good story pacing is varied sentence structure. Look at the Examples below.

Example #1: Short Sentences (~1-8 words)

Use Case: Action and combat scenes, suspenseful transitions, dramatic moments.

Bad: He ran. He stopped. He looked. He panicked. (too choppy, monotone)

Good: He froze, pinned to the spot. Footsteps drew nearer. His pulse quickened. Surely the killer could hear his heart hammering away in his chest. He needed to catch his breath. He also needed to escape. (punchy, dramatic, builds tension)

Effect On Pacing: Speeds up action; creates tension; reads as abrupt or punchy.

This sentence structure is great for scenes that need to move quickly. Naturally, the shorter the sentence, the easier and faster it is for the reader to move through the text. Overuse results in flat, boring, and emotionally-disconnected scenes. This structure is best used when the reader has already made an emotional connection to the characters in the story and the stakes are higher.

Example #2: Medium Sentences (~ 9-20 words)

Use Case: Versatile, used in most narrative passages, dialogue, in between action and revelation (can be used for these situations too).

Bad: N/A. Medium sentences are rarely bad, so long as word choice, word count, punctuation, and clauses are balanced.

Good: The wind groaned through the trees, as she made her way home, a bittersweet feeling settling in her chest.

Effect On Pacing: Smooth, natural rhythm; balanced pacing.

This sentence structure is most common in any published work, and it’s typically comprises the majority of a text. It’s the middle ground for sentence structure, tucked neatly between short, choppy sentences, and long, complex sentences. I like to think of it like the Goldilocks Effect: medium sentences are just right.

Example #3: Long / Complex Sentences (21+ words)

Use Case: Descriptive scenes, internal monologue, world-building.

Bad: Running down the narrow, cobblestoned street that wound unpredictably between the dimly lit shops whose windows reflected shadows of passersby who themselves seemed unsure of which way to go, he tried desperately to remember the route that would lead him safely back to the square. (too convoluted)

Good: Walking down the narrow, cobblestoned street, he remembered the stories his grandmother told about the town, imagining the faces of people long gone.

Effect On Pacing: Slows pacing; allows description, reflection, inner thoughts, (lowers tension back to or below baseline, to rise again later on).

This sentence structure is most common to fantasy and science fiction, where readers expect lore drops frequently but not excessively. These longer sentences can also appear in scenes where there is little or no dialogue.

Story structure can help you with pacing

Much like sentence structure, story structure can be a great way to determine the pacing of your story and where you might be doing really well in terms of tension and pacing and where your story might be sagging a little. The 3-Act Story Structure is just one example.

I think a lot of writers have a hard time with pacing because many of us grew up learning about the 5 elements of plot with a very set-in-stone triangular structure, but I like to think of plot as more of a bell curve. In the graphics below, you’ll see the 5 Elements of Plot (based on Freytag’s Pyramid) versus the Plot Bell Curve (based on the 3 Act-Story Structure) and how pacing looks with each of these story structuring methods.

The issue with the Elements of Plot is that this structure allows entirely too much time to pass between major plot points. This is where many writers’ issues with the “sagging middle” originate from. Look at the bell curve, where tension is kept evenly from plot point to plot point. Instead of a terribly slow and steady incline, the rising action builds tension right from the inciting incident and falling action slows tension from the midpoint to the confrontation.