Find Your Exact Genre, Find Your Lifelong Book Ambassadors by Shayla Raquel

This blog post was written by a human.Hi readers and writerly friends!

If you’re a returning reader, welcome back and if you’re new here, thanks for stopping by! For this post, fellow Oklahoma Freelance Editor Shayla Raquel is taking over the blog to tell you all about how to not only grow your audience but how to transform readers into lifelong ambassadors of your book! This post shows you exactly how to gain a clear understanding of your genre and target audience to grow an enduring, loyal readership! Be sure to leave her a comment and check out her website and other socials!

A best-selling author and public speaker, Shayla Raquel teaches people the ins and outs of writing, publishing, and marketing their books. Her in-person and online classes focus on author branding, self-publishing, book marketing, and the craft of writing.

She is the author of the Pre-Publishing Checklist, “The Rotting” (in Shivers in the Night), The Suicide Tree, The 10 Commandments of Author Branding, All the Things I Should’ve Told You, and “Savage Indulgence.”

In her not-so-free time, she studies all things true crime and obsesses over squirrels. She lives in Oklahoma with her husband and three fur babies.

More recently, Shayla has served as the founder of an incredible non-profit organization based in McLoud, Oklahoma, called Crime & Compassion Inc., through which she helps incarcerated women find their voices and share their stories with the world through their writing.

Shayla Raquel, best-selling author, public speaker, and book editor.

Why Do I Need To Know My Target Audience?

Investing time and money into social media, email newsletters, Amazon ads, podcast interviews, and blog posts will net you very little ROI if you do not know your precise genre.

Because if you don’t know exactly what book you wrote, then, my friend, you don’t know your audience.

And if you don’t know your audience, what good is all that time and money you’ve put toward marketing your book?

My goal today is to teach you how to determine your exact genre as a novelist so you can pinpoint your target audience. Once you do that, you can have lifelong book ambassadors: people who fangirl over your book and tell the world about it.

Amazon Kindle Categories. Photo by Shayla Raquel.

So, What Is Your Genre?

If I ask an author, “What book is your genre?” and they reply “Fantasy,” I get a little worried.

Go to Amazon.com and toggle the search bar from All Departments to Kindle Store. On the left-hand side of your screen, select Kindle eBooks. (We don’t need the newsstand or singles or anything like that.)

Next, select Categories. It’s easy to miss sometimes because Amazon doesn’t make it prominent, but it’s usually under the search bar or off to the left-hand side.

Next, for this purpose, select Science Fiction & Fantasy. Narrow it down once more by selecting Fantasy. There are over 50,000 e-books in the Fantasy category alone. That’s a lot of competition.

Now you have to determine where your novel fits in the world of fantasy. Before I explain, I have a very important note: I desperately wish authors would do this exercise before writing their novels. If they did, then they’d ensure their story fit within the expected storylines of, let’s say, Gaslamp Fantasy or Arthurian Fantasy.

Next, select Fantasy. Photo by Shayla Raquel.

My point: Your novel will be difficult to sell if you wrote it without knowing its genre. You can figure it out, but it’s a little bit tougher because there’s a chance there are several genres packed into one story. (I did this with my first novel, so don’t be like Shayla!)

Okay, now that you have a warning to heed, let’s move on to subgenres.

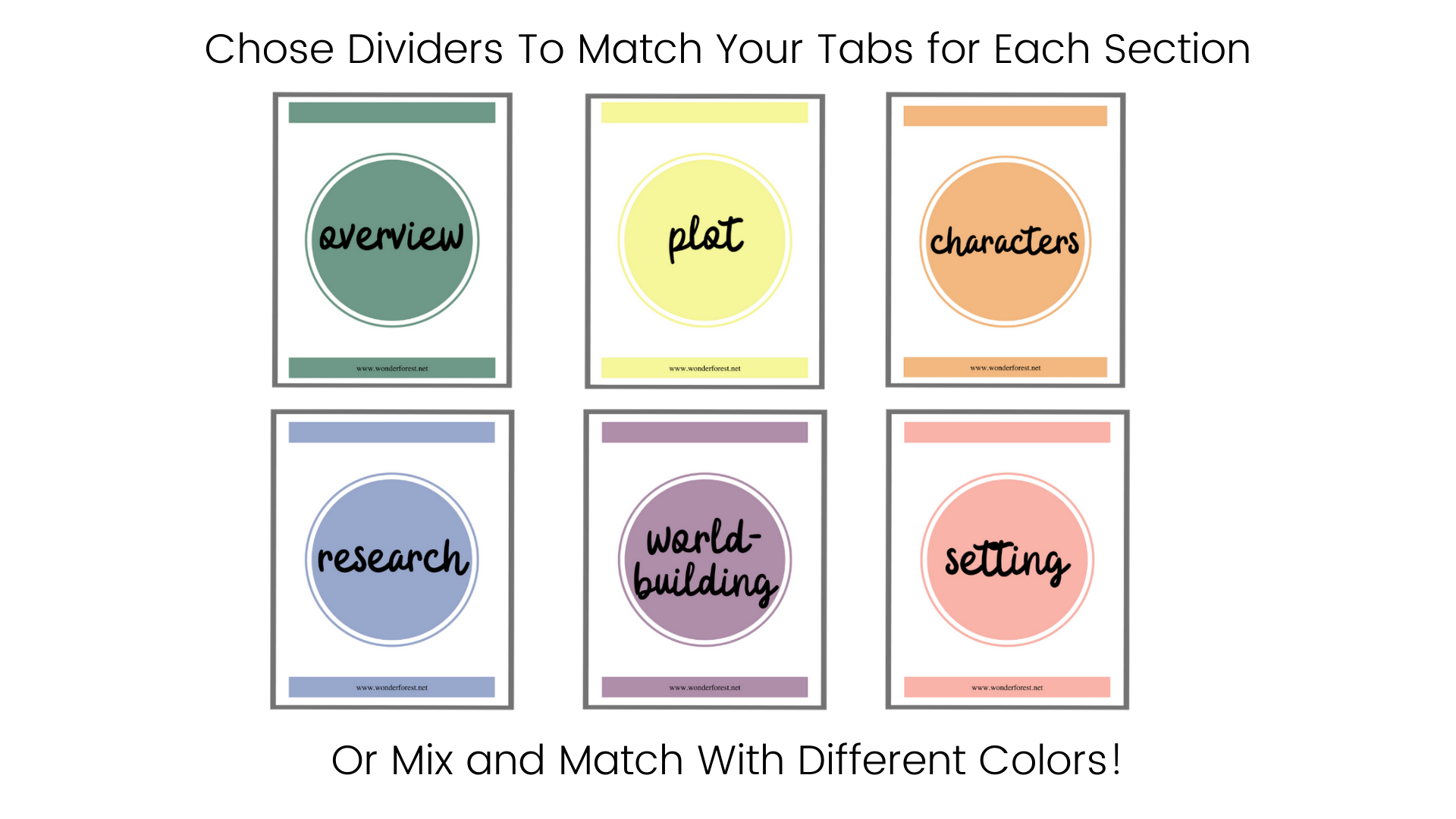

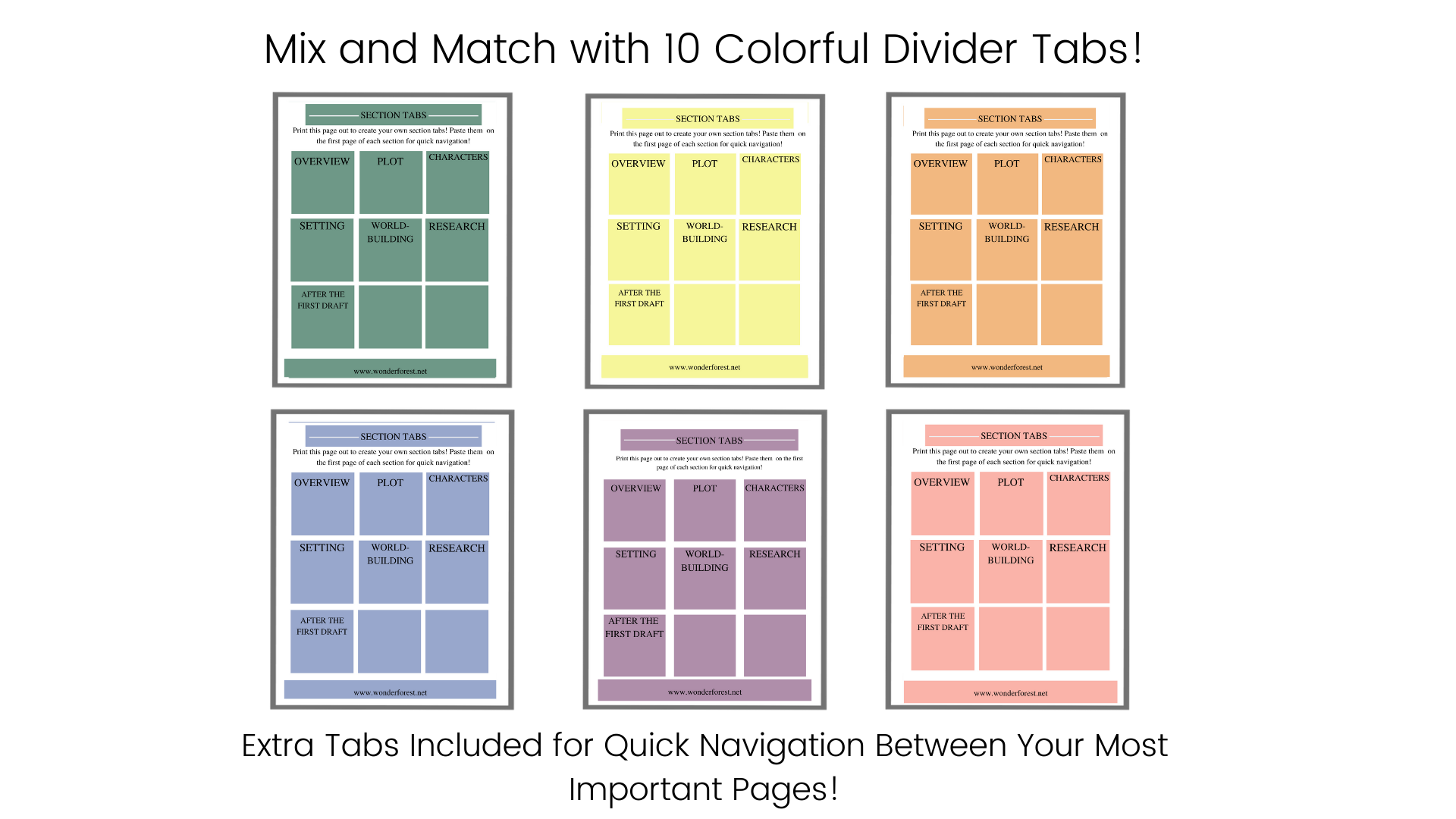

So here you are in the Fantasy genre for Kindle e-books with all this competition. Where does your book fit? If your subgenre is Action & Adventure, that’s more specific than just saying Fantasy, but could you niche it down even more by mentioning the types of characters? (Amazon gives us a handy checklist for various genres.) If you have Elves or Fae, that officially means you’re only competing with 1,000 e-books now!

Elves. Photo by Shayla Raquel.

Your genre would be, let’s say, Fae Action & Adventure Fantasy.

Let’s shift to Mystery, Thriller & Suspense. If you’re going to find your niche, I suggest looking into Moods & Themes (another handy checklist). If I write Crime Fiction (50,000 e-books in this genre), I have several subgenres within that too:

Heist

Kidnapping

Murder

Noir

Organized Crime

Serial Killers

Vigilante Justice

Crime Fiction. Photo by Shayla Raquel.

But I have the opportunity to get super specific by selecting a mood or theme, such as Action-Packed. Therefore, it would be: Action-Packed Heist Crime Fiction.

Action Packed. Photo by Shayla Raquel.

It gets better! I can also look into Settings (beaches, islands, mountains, etc.) and Characters (amateur sleuths, British detectives, gay protagonists, etc.) on the Amazon checklist.

Setting. Photo by Shayla Raquel.

Characters. Photo by Shayla Raquel.

If your story has some love in it, you would go to the Romance category and narrow it down to, maybe, Time Travel. On the left-hand side, take a look at Romantic Heroes and Romantic Themes (originally called Tropes). By narrowing the genre down to Viking Time Travel Romance, I have certainly found a very specific group of readers!

Vikings. Photo by Shayla Raquel.

Now What?

Now that you know some tricks for finding your exact genre, you have a foundation for marketing your book to the right audience. And marketing it well.

But how do you get book ambassadors to see your book?

It depends on the platform, of course. If you label your categories and keywords properly through Amazon KDP and Amazon Author Central, you’ve just made your life way easier. (To learn how to request 8 additional categories and how to find keywords, read 5 Freakishly Helpful Amazon Tricks Every Author Should Use.)

Outside of Amazon, your blurb (back cover copy and Amazon product description) must reflect your genre. In addition to a steller book cover, a blurb helps sell your book. It’s your big flashy billboard: it’s meant to suck the reader right in.

When writing a blurb, follow these steps:

Drop the Hook — A hook is meant to entice the reader to bite. I love this hook from The Martian by Andy Weir: “Six days ago, astronaut Mark Watney became one of the first people to walk on Mars. Now, he’s sure he’ll be the first person to die there.”

Dangle the Characters — Reel them in with intriguing characters.

Dive into Conflict — Show them what this book is all about. What’s the plot? Why should the reader buy this book?

Determine the Consequences — What hangs in the balance for your characters? Formula: Conflict (“Character must do this”) + Stakes (“Or this will happen”) = Consequences.

Dine on the Big Question — End your blurb on an intriguing question or a point of tension—something that will convince the reader to take a chance on buying your book.

For the complete how-to, read Writing Compelling Book Blurbs.

If you’ve got these things down (genre, Amazon, and blurb), you need to spend quality time putting your book in front of people on various platforms to determine where you get the most bites (from readers who want to chow down on your genre). It could be through any one of these avenues:

Social media (especially TikTok)

Email newsletter (your own)

Podcasts (interviews specifically)

Book promotion newsletters (Book Gorilla, Many Books, Book Rebel, etc.)

Amazon ads

Social media ads

Book reviewers (YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok are full of reviewers)

Blogs

Some platforms work better than others for a variety of reasons, but you won’t know until you try and stay committed long enough to determine if it’s worth the ROI. If you write sexy stories, there is a community with 4.2 billion views on TikTok called SmutTok just waiting for you. If you want your book to be reviewed, there are loads of BookTubers on YouTube ready and willing to geek out over your book.

If you will do the hard work of determining exactly what you write, it will be smoother sailing when it’s time to find your readers.

Best of luck!

Thanks for reading Shayla’s guest blog post! I hope you enjoyed it and found her advice useful and actionable! If you liked this post, please leave us a comment below and don’t forget to check out the other posts on the blog!

Bibliography

Raquel, Shayla. “Find Your Exact Genre, Find Your Lifelong Book Ambassadors.” Blog Post article and photos, February 3, 2023.furkanfdemir. “Classic wooden shelves with assorted books in store” (Thumbnail photo). Pexels photo, December 28, 2020.

Further Reading

“Writing Compelling Blurbs: Book Descriptions to Entice Your Reader.” by Shayla Raquel, June 28, 2022.“How Not to Launch a Self-Published Book: 7 Easy Steps for Indie Authors.” by Shayla Raquel, October 18, 2022.“Bad Book Marketing: Three Things Authors Need to Stop Doing Immediately.” by Shayla Raquel, March 20, 2022.“5 Freakishly Helpful Amazon Tricks Every Author Should Use (2022).” by Shayla Raquel, January 17, 2022.Or you can just check out all of Shayla’s blog posts about book marketing here!Crime & Compassion Inc.—Literature written by those who were written off—a 501(c)(3) registered nonprofit in Oklahoma.

More Like This

8 Reasons Why Having A Creative Community MattersThe Importance of Befriending Your Competition20 Tips and Tricks for a Successful Email NewsletterBook Marketing 101: Everything Writers Need To Know About Literary Agents and QueryingSee all Marketing blog posts.

Related Topics

8 Ways To Level Up Your Workspace And Elevate Your ProductivityYoga For Writers: A 30-Minute Routine To Do Between Writing SessionsHow To Overcome Writer’s BlockWriting Every Day: What Writing As A Journalist Taught Me About Deadlines & DisciplineWhy Fanfiction is Great Writing Practice and How It Can Teach Writers to Write WellCheck out my other Writing Advice blog posts!

Before You Go

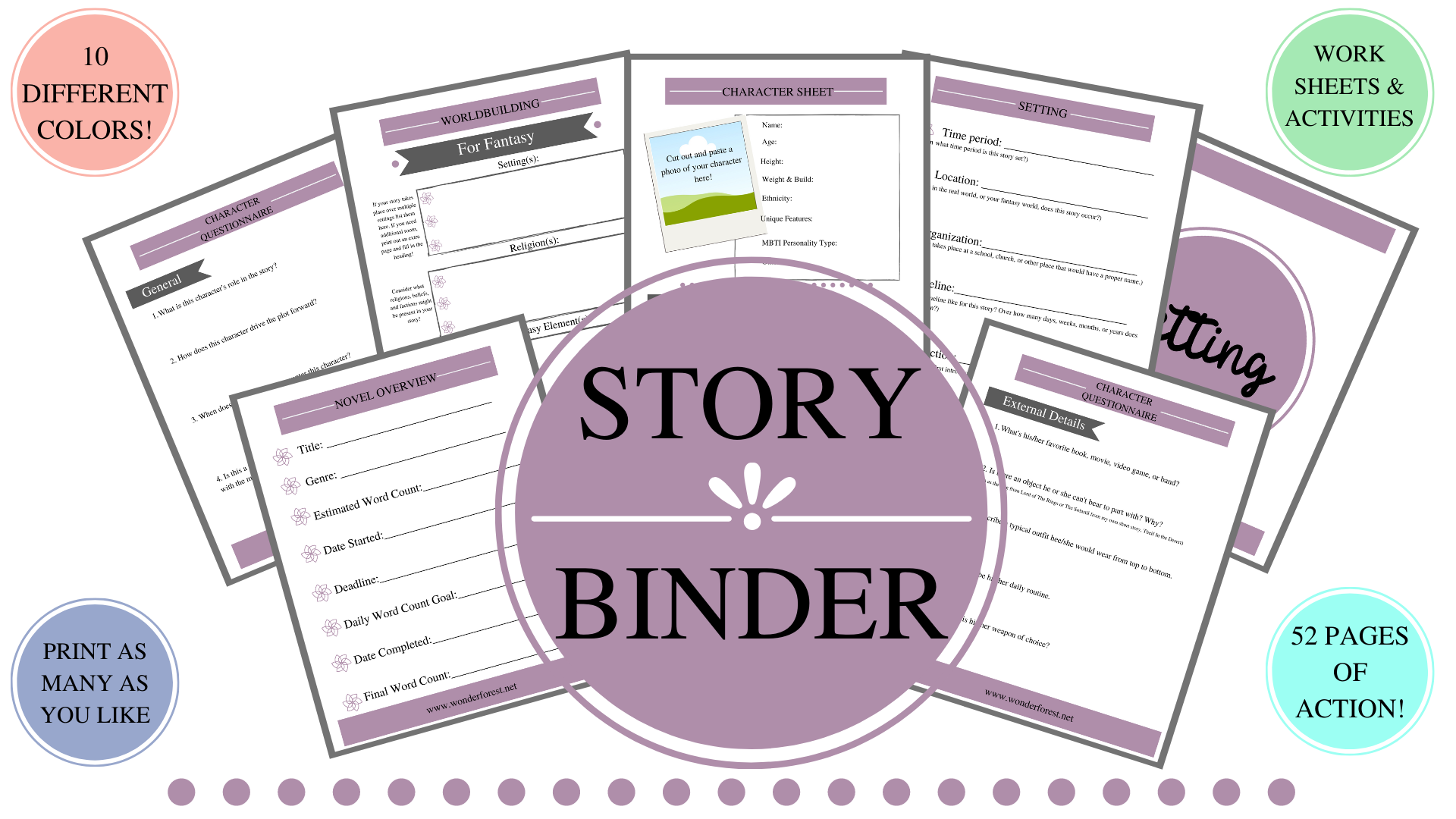

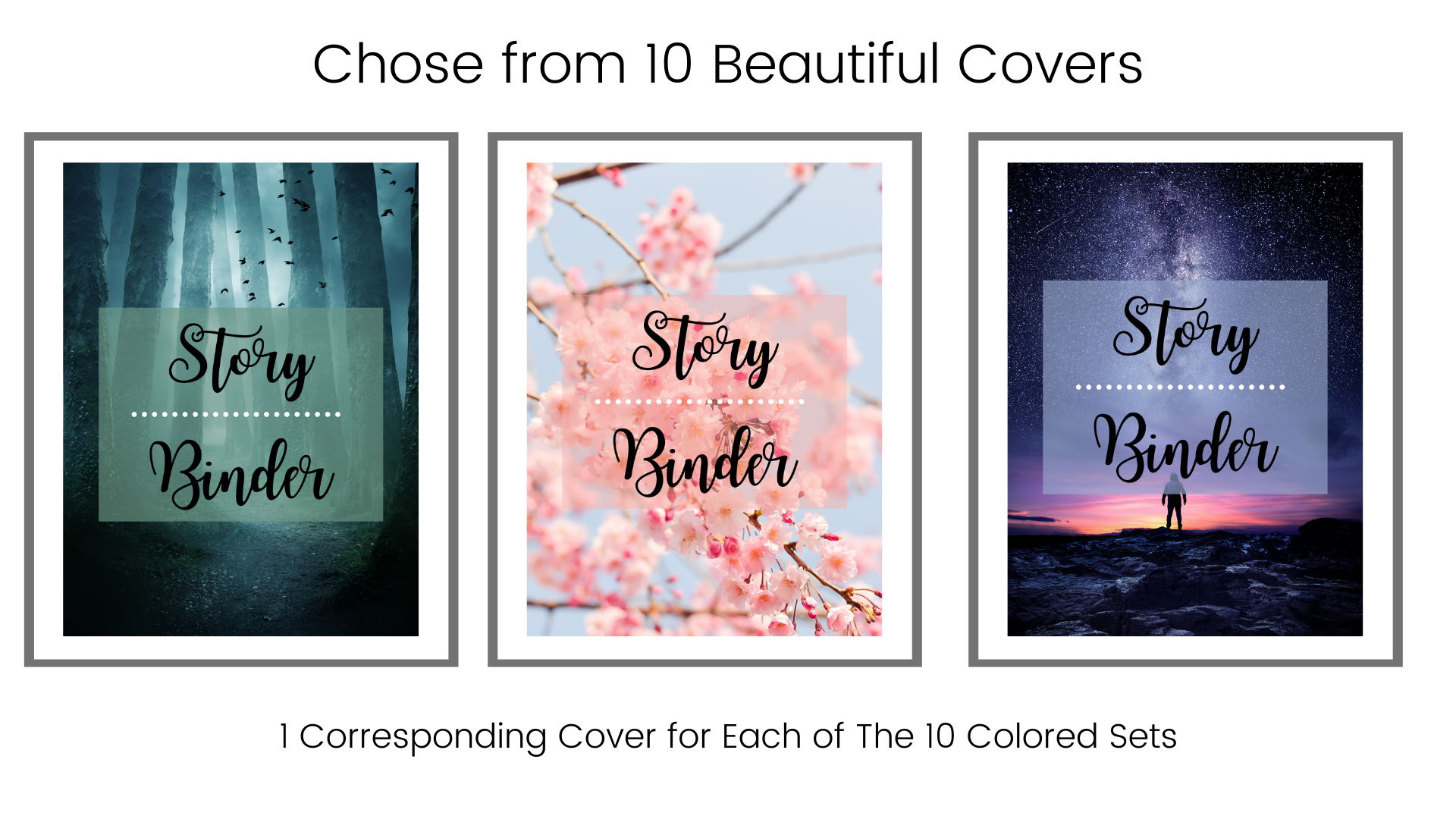

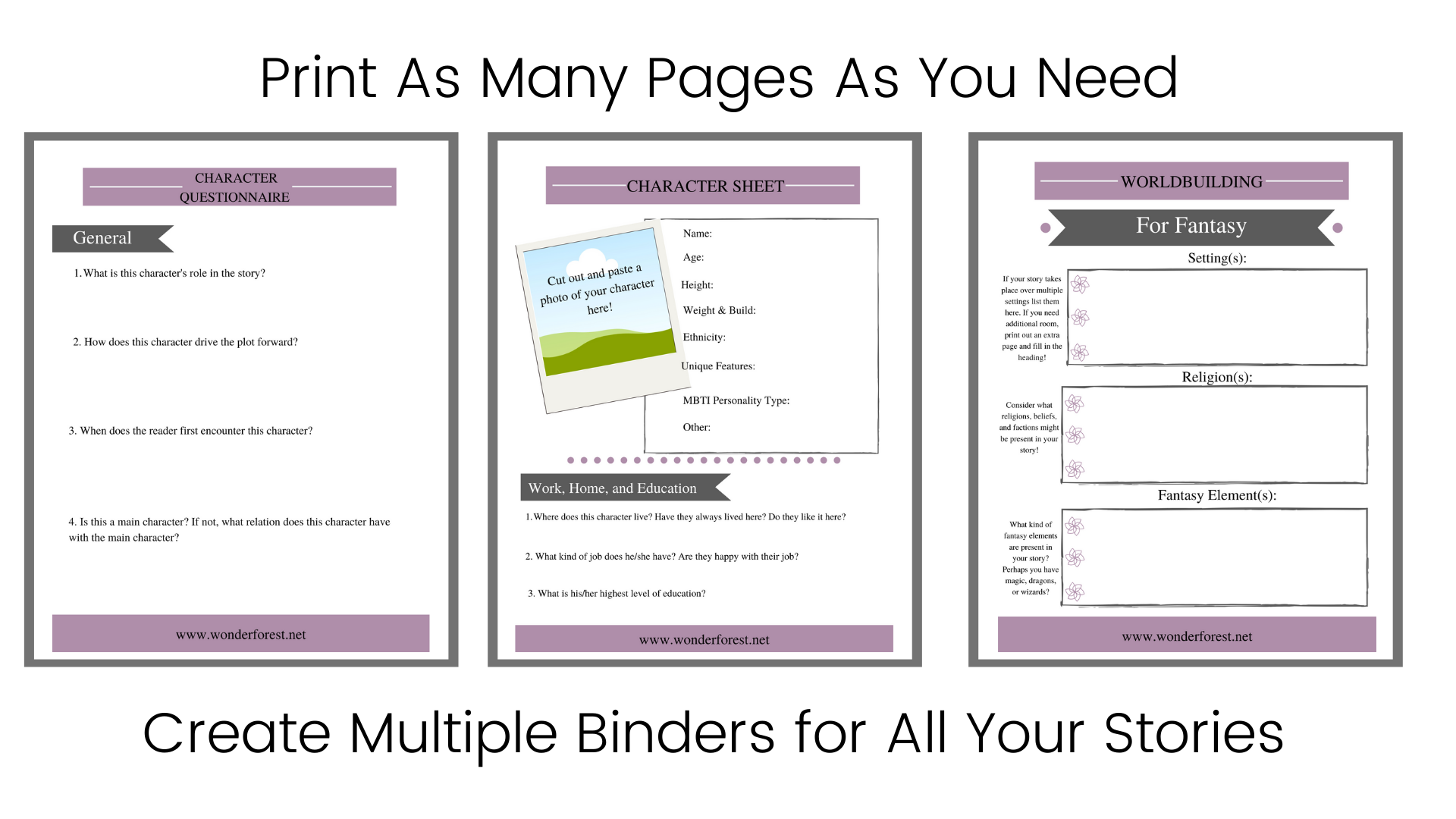

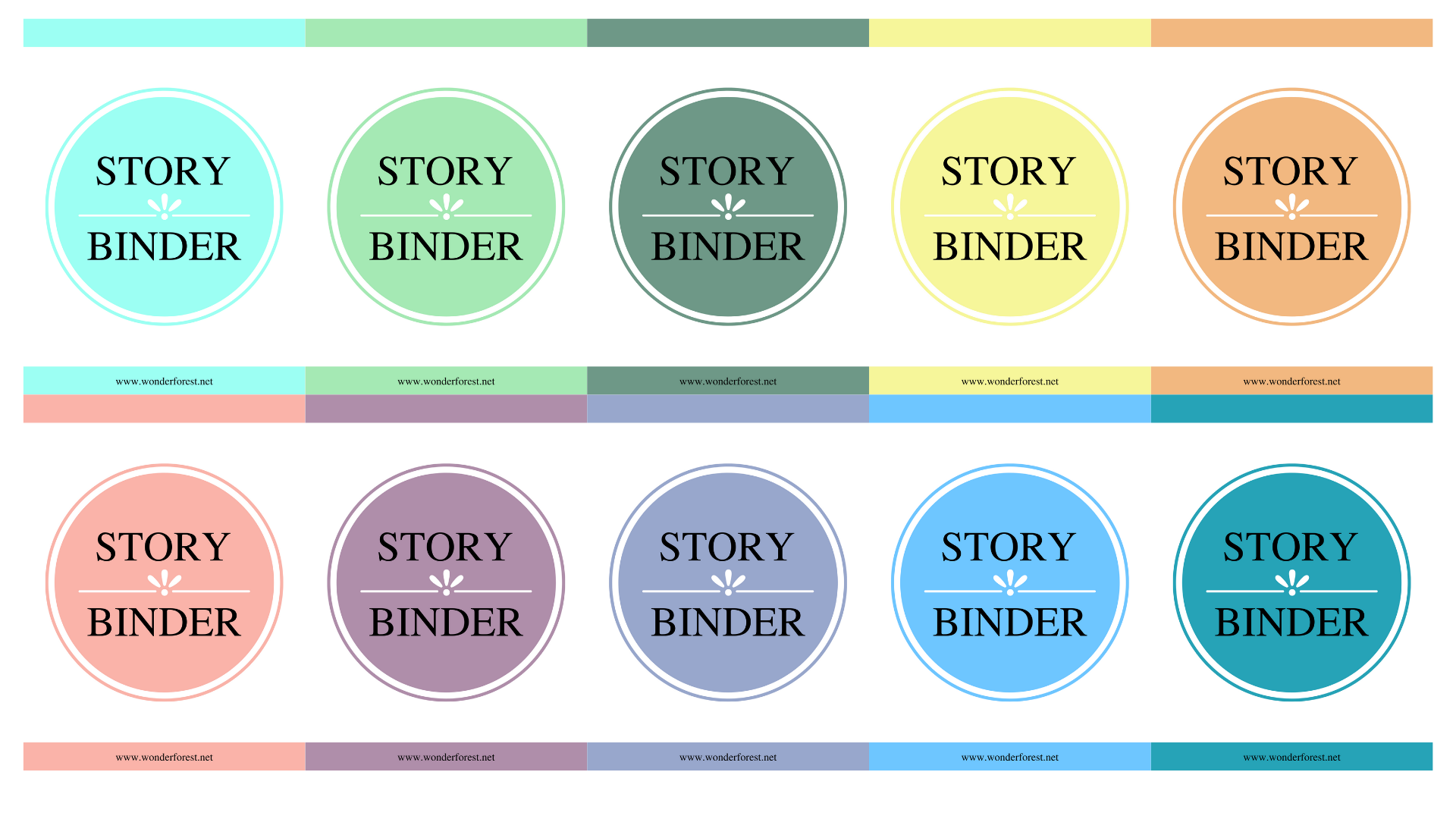

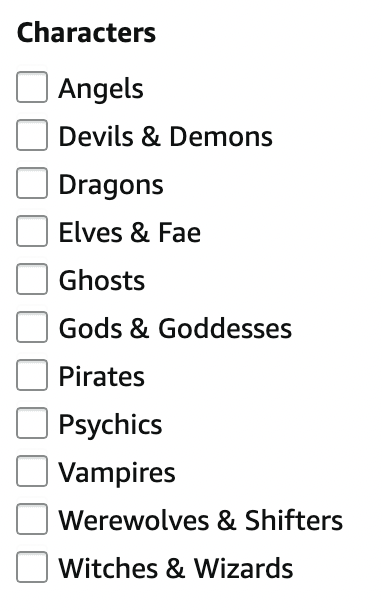

Looking for your next read? I've got you covered. See my Reading Recommendations and Reading Challenges for ideas about what to read next!Oh, and don't forget to Get Your FREE Story Binder Printables e-Book!

Recent Blog Posts

15 Misconceptions About Freelancing

Freelancing is often surrounded by misconceptions that can mislead those considering this career path. One common myth is that freelancers lack job security; however, many freelancers build stable careers by diversifying their client base and continuously marketing their services. Another misconception is that freelancers earn less than traditionally employed individuals; in reality, many freelancers match or exceed their previous salaries, especially as they gain experience and specialize in high-demand niches. Additionally, the belief that freelancers have no bosses is misleading, as they must answer to clients and adhere to project requirements and deadlines. The notion that freelancing is less legitimate than traditional employment is unfounded, as freelancers are recognized as independent contractors and contribute significantly to the economy. Finally, while some assume freelancers are socially isolated, many actively engage in networking, collaborate with clients, and participate in professional communities, maintaining robust social interactions. By understanding these misconceptions, freelancers, their clients, and everyone else can glimpse a clearer picture of what it’s like working independently.

This blog post was written by a human.Hi readers and writerly friends!

If you’re a returning reader, welcome back and if you’re new to the blog, thanks for stopping by! In this post, we’ll discuss fifteen misconceptions about freelancers (writers, editors, artists, entrepreneurs, and content creators). There’s a lot of stigma surrounding freelancing and the instability of working for oneself. Many people who aren’t freelancers or entrepreneurs have misconceptions about freelancing and I’m here to debunk them!

Many of the misconceptions surrounding freelancing are based in ignorance and I can understand how people looking from the outside in may have these ideas about freelance work. While some of these may be true for a portion of the freelancer population, they’re certainly not true for the majority. Every freelancing business is unique and comes with its own set of challenges. What makes some of these misconceptions truths and some of them myths is how freelancers handle those challenges.

This is not a complete list, but some of these misconceptions and myths about freelancing include:

You own your own business

You don’t have a boss

You can work whenever, wherever, (and however) you want

You only have to work on projects you like

Freelance work is always exciting

Freelancers make more money for less work

Freelancers make less money

There’s no job security

As a freelancer, you don’t have employee benefits

Freelancing is more stressful than a full-time job

Freelancers should work for free

Freelancing isn’t 100% legit

Freelancing hurts real businesses

All freelancers want to get a “regular job”

Freelancers are socially awkward

You don’t have to be a boss to be your own boss

While this is true for many freelancers, it’s not necessarily true for all of them. Many freelancers are employed by other entrepreneurs and still have to report to a boss.Even if you’re a freelancer, running your own small business from home, you still have to answer to clients and colleagues whom you work with. As a freelancer, your boss is the client.

You can work whenever, wherever (and however) you want / you only have to work on projects you like/ freelance work is always fun

Freelance workstation in a coffee shop. Photo by Toa Heftiba.

Many successful freelancers have the freedom to pick and choose to some degree, the projects they agree to work on. However, when work gets low, and clients are sparse, the pressure to agree to whatever work comes your way is higher than ever. As someone working for themselves, freelancers typically have to work harder to deliver a quality product. However, it is true, to some degree, that freelancers can work where they please. As long as they’re working for themselves or if they have a lenient boss, they can work from home, a library, a coffee shop, or from the park; they just need a place where they can focus on their work and avoid distractions.

Likewise, freelance work is not always enjoyable or exciting. Freelance work can be tedious and grueling some days and often consists of administrative work and accounting. As mentioned in the next misconceptions below, many freelancers who are just starting out often have to take what they can get, and this means they can’t afford to be picky about jobs. As a result, a lot of novice freelancers end up taking hard or boring jobs to make ends meet and build out their portfolio for hopefully better-paying, more interesting jobs in the future.

Freelancers make less money and/or do less work

Many freelancers charge less than the larger companies they compete with to give themselves an edge. Many other freelancers charge within industry standard and offer sample services to demonstrate their skills and quality of work. Many other freelancers charge above industry standard because their skills and services are worth the expense and they have the credentials and testimonials to back it up. Freelance pay depends on your field and how in-demand your skills/services are. Starting out, you may have to build a reputation and possibly accept lower paying jobs to build a strong work history. Testimonials, reviews, and referrals are excellent ways to boost client confidence in your abilities.

There’s no job security for freelancers

While freelance jobs are known for instability or unpredictability, the idea that there is no job security in freelance work, is just false. It depends on what you consider job security and what level of security you’re looking for.

It can be argued that standard day jobs don’t have job security, because if you’re an employee working for just one company or organization, you could be fired, losing your only source of income. However, if you’re freelancing, and you’ve got a few different clients, losing one at a time, would not cost you your only income. Replacing a single client can be much easier than finding another full-time job. It seems finding clients is somewhat less competitive than applying for a job to which many other people are also applying.

Freelancers get zero company benefits

The more savvy freelancers just might surprise you with this one. A freelancer might not have a traditional 401K but that doesn’t mean they don’t have great health care and long-term savings. Many freelancers also have the privilege to take longer vacations and more often. They often have just as many or more sick days at their disposal than typical employees and they can pick and choose their insurance benefits from a wide array of companies, rather than having to enroll in just what their employer provides.

Freelancers clutching her head in stress. Photo by Elisa Ventur.

Freelancing is more stressful than a typical 9-5

For some freelancers this is true. As mentioned above, freelancers who are just starting out may have to settle for challenging or boring/tedious jobs in order to cover their bases. And many seasoned freelancers still struggle with stress due to other factors such as family and lack of time management. However, many freelancers have figured out how to manage time, stress, focus, finances, and work-life balance which translates into lower-stress positions with more pros than cons. I think this one specifically is influenced by 1) the field and demand of services/skills and 2) the freelancer’s approach to work.

Freelancers should work for free / freelancing isn’t real work

Yeah, right! Try telling that to the IRS! Freelancers are considered independent contractors and they are generally required complete a 1099-MISC or similar form for taxes. And freelancers often work long hours and produce thoughtful, quality work as a result and should certainly be paid for their services. Freelancers not delivering on their end of the bargain should be confronted and asked to rectify this. One way to avoid this is to provide sample work, testimonials, referrals, and reviews to demonstrate skills and services.

Freelancing hurts real businesses

You might be surprised to hear that the opposite is true, actually. Often, small companies that cannot afford to hire full time employees may rely on contracted work to keep their business running. They may sometimes collaborate with other freelancers to meet their needs on a budget too. Freelancing does not hurt businesses; it stimulates the economy and allows more consumers to participate in the free market. Freelancers also give the market alternative options to large corporations with a large price tag.

Freelancers have multiple jobs or have to supplement their income

While many people do freelance work to supplement their income, there are also many freelancers whose first picks would be freelancing because of the benefits and freedom it provides. Freelancing is especially appealing to the millennial generation, who are less productivity-focused and more meaningful-work -focused, non-traditional families, and entrepreneurs.

Freelancers meeting at a coffee shop. Photo by Brooke Cagle.

Freelancers are socially awkward

Another common misconception about freelancers is that they are socially awkward, are hermits, antisocial, or loners. While many freelancers prefer solitary work (for many different reasons including creative control, time management, and freedom,) many work alone simply due to the nature of freelance work. Some freelancers collaborate with other freelancers which helps them network and build connections with others in their field and related fields. Others don’t mind working alone and find they are able to focus better when not working as part of a team.

Freelancing isn’t for everyone and it's certainly not always easy or high paying. Learning the ropes, practicing and honing skills, building a portfolio and client base, networking, and working from the ground up is arguably more challenging, more daunting, and more physically, emotionally, and mentally taxing than just showing up to a 9-5. However, freelance work can be incredibly rewarding and fulfilling and it gives entrepreneurs the ability to make an impact on the world, and to enjoy what they’re doing.

That’s it for my list of 15 Misconceptions About Freelancing! Have you heard any of these misconceptions? Do you think they’re true? Why or why not? What are the misconceptions you have heard that aren’t on this list? Let me know in the comments! Thanks for reading!

Bibliography

Cagle, Brooke. “Freelancers meeting at a coffee shop.” Unsplash photo, November 26, 2018.Harris, Mikey. “Working from home.” Unsplash photo, June 5, 2020. (Thumbnail photo).Heftiba, Toa . “Working Space.” Unsplash photo, August 16, 2018.Venture, Elisa. “A business woman who is stressed and frustrated,” Unsplash photo, May 17, 2021.

Related Topics

Get Your FREE Story Binder Printables e-Book!Freelancing Basics15 Misconceptions About FreelancingEditing Misconceptions: Book Editors Aren’t Monsters20 Tips and Tricks for a Successful Email NewsletterHow To Submit Your Writing To—And Get It Published In—Literary Journals8 Reasons Why Having A Creative Community MattersThe Importance of Befriending Your Competition4 Of The Most Useful FREE Apps For Writers (2022)Payton's Picks: The Best Books On Writing BooksCheck out my other Freelancing posts!

Recent Blog Posts

For Content Creators and CEOs with ADHD: Strategies to Succeed Despite Overwhelm and Distractions

Learn how CEOs and content creators with ADHD can thrive amid overwhelm and distraction. Discover practical ADHD-friendly systems—like daily planning tools, the Pomodoro Technique, and chunking strategies—from author Payton Hayes. Boost focus, eliminate burnout, and build sustainable routines that enhance leadership and productivity.

This blog post was written by a human. Hi readers and writerly friends!

As someone with severe adult ADHD, I personally know how this neurotype can affect one’s personal and professional life. ADHD is a neurodivergence, not a disorder, and worth looking into whether or not you have been diagnosed with it. Readers and writers, I’ve created a list of tips and tricks (ADHD friendly) that can help you in your business whether neurotypical or neurodivergent, like myself. If you’re in a rush, check out the headers and sections in bold to get the most out of skimming this post.

Note: Some of the advice in this blog post is from my own personal experience, tips and tricks from other people I know who have ADHD, and the book, Mastering Your Adult ADHD: A Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment Program, Second Ed. Client Workbook by Steven A. Safren. Any quotes from the workbook are cited in-text and at the end of this post (Safren 2017)

Rearrangeable Corkboard Calendar. Photo by Monica Sauro.

Calendars, Planners, and Daily Task Lists

As per the workbook and my own experience, having a toolkit of simple, practical, sustainable, and daily organization and planning tools is key to combatting prioritization-confusion, time-blindness, and forgetfulness in general. This is true for people with and without ADHD. Having a 3-step planning system ensures consistency and employs repetition —a useful tactic for remembering important tasks day-to-day, week-by-week, and month-to-month. I’ve been using this system for three months now, and it has changed how much I can get accomplished in a single day. I’m not advising you go overboard with adding tasks to your plate and burn yourself out. But you’ll be amazed at the productivity and action you can achieve by employing a simple planning routine that can be scaled up or down and modified in many ways to fit many different lifestyles and stages of life.

How to execute this planning strategy:

Use a Calendar for a monthly view. This can be paper or dry-erase calendar, but make sure its simple and big enough to write 1-3 important tasks, appointments, or events in each day’s space.

Use a Planner or weekly agenda for keeping up with tasks throughout the week. Realistically plan your days so that you can get your professional and personal work done in a timely manner without overworking yourself. Unless you can consistently produce quality results, stick to no more than 3-5 tasks a day until this becomes a habit. Pick out a planner that you like and avoid choosing frills over functionality. The more space the better. I prefer just a plain planner with a calendar view for each month and a few lines for each day of the month in an agenda format. Ensure the planners size can accommodate your handwriting as well as portability, because this will be your middle-man between your home calendar and task list as well as your point of reference when away from home.

Use a Daily Task List for daily task planning and organization. Again, limit your responsibilities to reflect your true capability and slowly add more tasks onto your plate when you feel comfortable doing so.

Pro Tip: Use the same color-coding system in your planner and task list as you do on your monthly calendar. Get colored pens that match your expo markers so that you can peek at either tool and read it at-a-glance, ensuring ease of understanding and consistency. Only use a color-coding system if it will benefit you, though. If you’re worried it will become too complicated, take too much time to set up, or you’ll get hung up on perfectionism, opt for 3 colors max, or skip this step altogether.

For Digital Planners: I would love to be more eco-conscious and go paperless, but the repetition of writing plans down 1-3 times helps me remember when and what I’ll be doing each day. This process also helps me to catch any discrepancies between one of my planning tools and I can catch mistakes (such as an event written on the wrong day of the month) much easier and usually before the event. However, if you’re really not one for writing things down and would prefer to go the digital route, there’s a few tools you can use to achieve the same 3-step planning system mentioned above.

Tablet displaying a virtual weekly planner. Photo by Jess Bailey.

Pick a good virtual calendar such as Google Calendar. Color-code events as needed and try to keep colors consistent across all apps and devices.

Use a good digital planner as well —below, I mention Notion as a great resource for note-taking but it can also serve as a fully-customizable virtual planner/agenda as well. If you’re overwhelmed by the customization, there’s a ton of other free and paid virtual planning/productivity apps out there!

Use a simple virtual notes app or list app such as Google Keep Notes or Google Tasks. Notes has more formatting options but Tasks has a satisfying check-off function for when you’ve completed tasks.

If you’re going the virtual route, use digital alarms to help you stay on track! The Pomodoro Technique is a great strategy for getting both quality work and breaks done in a timely manner. If you’re not going digital, keep hand-held timers around your house or at your desk in the office to use to help with time management.

The workbook provides some rules for effective use of the calendar and task list:

Rules for the Calendar and Task List

The calendar and task list system replaces ALL pieces of paper

Pieces of paper just get lost.

Instead of keeping an appointment slip, a business card, or anything like this, copy the information onto the task list or enter it directly on your calendar.

Phone messages from voice mail or other places go on the task list.

Log every phone message (from voice mail and so forth) on the task list as a to-do item.

If you date when you have completed the task, you will then have a record of having done it in case anyone asks you about it in the future.

All appointments go on the calendar.

No appointment slips that can easily get lost!

All tasks must go on the task list.

Task list items should be looked at EVERY DAY, and revised accordingly.

Do not obsess about trying to get a perfect system.

Many individuals want to have the perfect calendar and task list systems. Do not fall into this trap! This will just result in not having any systems.

If you cannot decide on the “best” system, then just use a simple calendar and task list system.

Remember it’s important to give your system a fair shot! This means keeping one system for at least three months, long enough to get used to it.

Use a system that is within your comfort zone.

There are many options for calendar and task list systems—including paper systems, applications on smartphones or tablets, and multiple computerized applications. Many of our clients ask us which is the “best” system, and this is not really a question that we can easily answer. The question for you to ask yourself is this: “What’s the best system for me?”

— (Mastering Your Adult ADHD, 29-30)

Manageable chunks

Downsize overwhelming parts into manageable chunks. Make step-by-step processes for tasks that seem daunting and go one step at a time. This will help you manage overwhelm, anxiety, and, unnecessary busy work. Make a list of items and order them according to due date or priority, and try to get them done as soon as possible. Do not wait until the last minute, no matter how tempting that next episode of Orange Is The New Black may be. Make a reasonable, executable game plan for your goals or project, and proceed one step at at time. Don’t get hung up on the details or perfectionism, just start.

“A good plan executed right now is better than a perfect plan executed next week.” —George S. Patton.

Woman looking through her weekly planner. Photo by Covene.

Task Prioritization with the A,B,C’s

Now that you know of an effective and sustainable planning strategy and you know to break overwhelming tasks up into more manageable steps, it’s time to prioritize. As mentioned earlier, without prioritizing tasks, its easy to get caught up in busy work. Getting a lot of tasks completed and crossed off your to-do list feels good, but is it really getting you closer to your goals? By being overly productive with mundane tasks, are you actually getting any important work done?

That’s where the A,B,C’s come in. I learned this strategy in the workbook as well:

List all of your tasks. Then assign an “A,” “B,” or “C” rating to each task:

“A” Tasks: These are the tasks of highest importance. They must be completed in the short term (like today or tomorrow).

“B” Tasks: These are lower-importance, longer-term tasks. Some portions should be completed in the short term, but other portions may take longer.

“C” Tasks: These are the tasks of lowest importance. They may be more attractive and easier to do, but they are not as important.

Be very careful not to rate too many items as “A”!

Practice doing all of the “A” tasks before the “B” tasks and all of the “B” tasks before the “C” tasks.

— (Mastering Your Adult ADHD, 34-36)

When first going over this concept, my therapist put it this way: “A” tasks must be done on the day they’ve been assigned to. “B” tasks can be moved to other days but not move more than a week away from their original date. “C” tasks can be infinitely moved and do not require a defined date/time. An “A” task might be going to a doctor’s appointment. A “B” task might be getting your car’s oil changed. A “C” task might be finishing a book you’re reading for pleasure. This prioritization strategy will look different for everyone, especially at different stages of life.

Just remember the priority: “A”= Highest importance, “B”=Medium importance, and “C”=Lowest importance. Avoid overwhelm and burnout by strategically spacing “A” tasks throughout the week if possible. Try to limit “A” tasks to no more than 1-3 things a day until you feel comfortable with this system.

Color-coding tasks instead: If you’d rather use a color-coding system for prioritization, traffic light colors Red, Yellow, and Green make a great color-combination for action! Red= Stop what you’re doing and do the most important tasks first. Yellow=Be cautious of time and complete the lesser-important tasks next. Green= Go! on tasks of lowest importance once you’ve completed Red and Yellow tasks first!

Just “Eat the Frog” or “Start”

Have you ever heard of someone eating the frog when it comes to content creation, their personal to-do list, or professional positions? This means to start with the hardest item or most difficult item on the to-do list. This item is typically something that requires research, planning, and time to execute. It is a task that requires more energy and time to complete. Often these tasks are called ”frogs” because they’re hard to swallow, or hard to get done and often include a lot of planning and/or procrastination. By getting them done early, one can look forward to the “downhill” slope throughout the day/list. Get the hardest task out of the way and it will be easier as the day goes on.

If you’re more of a “work your way up” to the hardest task from the easiest tasks, that’s okay too! Not everyone feels comfortable starting with the “frog".” Just make sure you’re not doing busywork or deluding yourself with a false sense of productivity. Ensure your actions and “warm-up” tasks are actually moving the needle, and getting you closer to your goals.

Make use of versatile apps and devices

I’m saving for an iPad and Apple Pencil so I can do digital artwork, digitize my existing physical artwork, and start creating unique animations for my YouTube channel. I’ve seen some pointillism artists doing dotwork with tattoo guns on paper, saving their hands the trouble and repetitive stress. Utilize the technology we have today to save time tomorrow.

Clickup’s Blog has tons of great resources for productivity and combatting ADHD. Greg Swan’s post “10 Best Mind Mapping Software (Pros, Cons, Pricing)” explains how mind-mapping can be a useful tool for productivity and breaking tasks down into actionable steps:

Mind map software lets you create a diagram or flowchart of your ideas. This helps you easily illustrate the relationships and hierarchy between concepts.

Most mind mapping tools come in different sizes to suit various needs, offering other functionality. Generally, your average mind map maker falls under one (or more) of these categories:

Diagramming: a technical diagram such as engineering flowcharts, architectural designs, network diagrams, etc.

Brainstorming: problem-solving sessions to organize and present an idea visually

Business intelligence: visualize data as charts by importing it from business applications

Software development: prepare site map diagrams, software wireframes, etc.

— (Swan, paragraphs 5-8)

Checkbox to-do list on paper. Photo by Thomas Bormans.

Take notes

When it comes to conventions, panels, educational videos, courses, classes and other avenues for creative information, remember to take notes —and not just cover vocabulary. Let’s get honest for a second, aesthetically pleasing notes make studying that much easier, for sure, but it’s not a necessary effort. As long as your notes are legible and cover important topics that will likely come up later (or for students, will be in the exam) then you are good to go. Feel free to digitize or edit your notes later. First, focus on jotting down as much information as possible.

Pro Tip: If you don’t feel confident in your ability to type as fast as the professor or speaker talks, then feel free to record the panel or discussion. Make sure you get permission/clearance before recording someone else. When you have time, type up and refine the notes into easily-digestible, succinct, effective, and at-a-glance notes. Put them on the wall, your vision board, or bathroom mirror to see them frequently until their concepts and advice is cemented solidly in your brain. Then, file your notes away in an organized fashion and make sure to refer back to them regularly.

Notion and other note-taking apps

I genuinely enjoy this app and the features it provides users. Notion has an almost overwhelming number of features and useful elements. I personally use the application to create lists, blog post rough drafts, flesh out poems, and to tack down other ideas, but this barely scratches the surface of Notion’s versatility. This post is not sponsored by Notion, nor am I affiliated with them.

Celebrate milestones, big and small

Don’t forget to celebrate hard work and milestones. Go out every once and a while to celebrate and acknowledge the hard work you’ve done. If the work is online, it can be especially hard to quantify successes or measure productivity, so go out every now and again and celebrate the small and big wins! Don’t. Skip. On. This. Even if you don’t drink, are veggie, or have a tight curfew, make sure you allow time for you to, celebrate both the small and big wins and really soak it in. When your supervisor gives you a compliment, treat yourself to a nice coffee, or when you meet a work or personal creative deadline early, grab that chocolate-chip muffin as treat (as long as your not on a diet, lol —look into other rewards systems if you’re alcohol-cruelty-gluten-free, etc.!”

FAQ pages

For entrepreneurs and creatives with websites, this page can save you a lot of time and trouble. Although it’s pretty self-explanatory, a Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ’s) page serves as a buffer between you and your reader’s repetitive, previously answered/address queries. Link the FAQ page in the footer or contact section of your website and put 5-20 of the most frequently asked questions there, to help avoid repetition and wasted time re-addressing the same questions over and over again.

Lead magnets

Sometimes called freebies, lead magnets are the little juicy bits of content that readers subscribe to your content in order to access. For cooking blogs, it may be a 20-page mini cookbook. For writing blogs, it may be a short guide for combatting writer’s block or a writing checklist. Just about any website can have a lead magnet and it’s the easiest, most automatic way to obtain an email address from a visitor to your site. Lead magnets are powerful, effective, enticing marketing tools and they’re very easy to create. Design a unique, actionable, useful piece of downloadable/printable content with an editor such as Canva and upload it as a downloadable file into your newsletter block on your website. Once the reader enters his or her email into the box and hits the subscribe button, they’ll be prompted to download the content they signed up for. Now you’ve unlocked another potential customer who you can market to, straight to their inbox, and they just gave you that access!

Minibatch and time-batch tasks

Similar to prioritization and chunking tasks into more manageable steps, minibatching tasks can serve as a useful strategy for planning, organization, optimization, and execution. To do this, break your larger tasks down into smaller, doable steps, then put those smaller tasks onto your calendar or planner, according to the type of activity required to complete the task. For example, if your car needs several maintenance tasks done, schedule a time to look at and order car parts, make appointments to the alignment shop and oil-change shop, and plan a day to get all the car work done. Another example, if you need to record videos, take photos, or hop on webcam, schedule these tasks all on the same day if possible. You’ll save yourself the time and trouble of getting ready for each individual appointment and get the most wear out of your outfit/makeup/hair-styling too!

Have frequent co-working sessions

Schedule in regular co-working sessions with friends, partners, and colleagues. These sessions are for working collaboratively on projects and brainstorming and are an amazing resource for creatives and office-workers alike. Friends can help you pick paint samples and the interior design of your living room, while colleagues can help you come up with new strategies for success in the workplace. Who says you can’t have coffee in the morning with a client in the morning and meet up with your bestie for lunch in the afternoon?

Schedule “people days”

Much like the time-batching tasks, schedule all of your face-to-face appointments, coffee-shop meet-ups, conferences, phone calls, and co-working sessions in the same day, when possible. This will save you time getting read for each appointment and once you’ve made it through the first meeting, you’ll be ready to tackle the next meeting as your confidence and productivity high snowballs you throughout the day.

ADHD management and CBT therapy

Regardless of if you’ve been diagnosed with ADHD or not, these tips can be useful for anyone who gives them an honest try because they’re practical, scalable, sustainable, effective, and simple. However, these tips may not be enough if your life is a hot mess like mine was in 2020-21. After having done my own ADHD management program and CBT program for PTSD, I can truly say it has changed my life for the better. I would recommend anyone struggling with ADHD symptoms to reach out to your primary healthcare provider and discuss options for treatment with them. Depending on the severity, you may require therapy, management, medication, or lifestyle changes in order to manage any debilitating or annoying symptoms you may have. I’m not a doctor —I just know this process helped me understand and embrace myself and gave me the patience and grace to work through my challenges without shame, fear, or judgement. Please do not diagnose yourself. If you feel you may be struggling with ADHD, contact your doctor or counsellor and have a formal assessment and diagnosis done.

Thank you so much for reading this blog post! If you liked this post, let me know what you thought of it in the comments below, and please check out my other posts! If you have any other actionable tips for productivity as a creative with ADHD, drop a comment below!

If you’d like to see more of my blog posts, consider subscribing below to get updates as soon as a new blog post is published! You’ll also gain exclusive subscriber-only access to the new and improved Story Binder Printables e-Book! Feel free to check out the recent blog posts linked at the end of this post as well!

Bibliography

Bormans, Thomas. “Free Pen Image.” Unsplash photo, August 30, 2020.Covene. “woman in white long sleeve shirt, holding pen, while writing on paper.” Unsplash photo, May 21, 2021.Fernandes, Nuberlson. “Man in white crew neck shirt wearing black framed eyeglasses.” Unsplash photo, February 27, 2021 (Thumbnail).Notion Labs Inc. “Notion - notes, docs, tasks.” Google Play Store, accessed 11, 2022.Safren, Steven A. Mastering Your Adult ADHD: A Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment Program, Second Ed. Client Workbook. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.Sauro, Monica. “Brown calendar photo.” Unsplash photo, May 16, 2019.Swan, Greg. “10 Best Mind Mapping Software (Pros, Cons, Pricing)” ClickUp Blog. October 13, 2022.

Related Topics

Get Your FREE Story Binder Printables e-Book!8 Ways To Level Up Your Workspace And Elevate Your ProductivityGet Things Done With The Pomodoro TechniqueHow To Organize Your Digital Life: 5 Tips For Staying Organized as a Writer or Freelancer5 MORE Ways To Stay Organized As A Writer Or Freelancer20 Tips and Tricks for a Successful Email NewsletterSelf-Care Tips for Bookworms5 Healthy Habits For Every WriterWriting Every Day: What Writing As A Journalist Taught Me About Deadlines & DisciplineYoga For Writers: A 30-Minute Routine To Do Between Writing SessionsCheck out my other Productivity & Organization Writing Advice, Freelancing, and Content Creation blog posts!

Recent blog posts

Book Marketing 101: Everything Writers Need To Know About Literary Agents and Querying

Literary agents play a pivotal role in an author's journey toward traditional publishing, especially with major New York publishing houses. They act as intermediaries between authors and publishers, leveraging their industry expertise to secure favorable book deals, negotiate fair contracts, protect writers' rights, and ensure accurate compensation. While securing an agent is often essential for mainstream fiction and popular nonfiction targeting large audiences, it may not be necessary for niche markets or academic works. Understanding the commercial viability of one's manuscript is crucial; not all books are suited for major publishers, and many find success with mid-size or independent presses. Aspiring authors should research market trends and maintain realistic expectations about their work's potential reach.

This blog post was written by a human.Hi readers and writerly friends!

If you’re a returning reader, welcome back and if you’re new to the blog, thanks for stopping by! In this blog post we’ll be covering everything from querying basics to how to find a literary agent and land a book deal in the 2020’s, when more than 75% of books published by the big five New York presses get sold by literary agents. Literary agents are experts in the publishing industry and can be career-long mentors and managers and there’s plenty of reasons why writers both new and experienced alike could benefit from hiring an agent.

Agents are market experts and can secure the best possible book deal for their clients as well as negotiating fair contracts, protecting the writer’s rights, ensuring clients are paid accurately and fairly as per industry standards, and ultimately serve as the middleman between the author and publisher.

In 2021, more than 75% of books published by the big five New York presses get sold by literary agents. Literary agents are experts in the publishing industry and can be career-long mentors and managers.

Do I Need An Agent?

Honestly, it depends on the commercial viability of your book. If you want to be published by one of the five major New York publishing houses, (i.e., Penguin Random House, Simon & Schuster, HarperCollins, Macmillan, and Hachette) then you’ll need an agent to be sure. However, if you’re instead writing for a niche market (i.e., time period fashion) or wrote an academic or literary piece, then perhaps you don’t need an agent. Agents take on clients based on the size of the advance they think they can for the project. If your book doesn’t command a decent advance, then the project may not be with the agent’s time and you’ll have to sell it yourself. Unfortunately, most writers have a difficult time being honest with themselves about their work’s potential. We all want to see our names on the New York Times Bestseller’s list, but that’s just not a realistic expectation. It comes down to this: not every book is cut out to be published by a New York house, or even represented by an agent.

There are different levels of commercial viability in the publishing industry. Some books are “big” and are suited for Big Five traditional publishing houses, while others are “quiet:” books and are suitable for mid-size and small presses. If you’re realizing your work might not be a good fit for one of the major publishers, don’t despair. There are many mid-size houses, independent publishers, small presses, university presses, regional presses, digital-only publishers who might be thrilled to have you work —you just need to find them.

These types of books typically are suitable for a major traditional publisher:

Genre or mainstream fiction, including romance, erotica, mystery/crime, thriller, science fiction, fantasy, young adult, new adult

Popular nonfiction you’d see stocked in Barnes & Nobel —contingent upon a strong premise and existing author platform.

Major New York publishers usually won’t sign a nonfiction book unless it realistically anticipates selling 10,000 to 20,000 copies minimum.

To better understand what sells, consider picking up a month-long subscription to PublishersMarketplace.com and study the deals that get announced. It’s a quick and inexpensive education in commercial publishing. I’d also suggest taking a peek at the agent database at Literaryagencies.com

When To Query

Naturally, the easy answer is once the book has been completed. Truthfully, there is no one size fits all approach to figuring out when you should query your novel, but the query questionnaire below might help you determine based on the state of your manuscript, feedback you’ve received, and your experience with the writing process, whether or not you’re ready to query.

What Stage Is Your Manuscript Currently In?

Incomplete/Rough Draft. Graphic by Payton Hayes.

Critique Groups & Beta Readers. Graphic by Payton Hayes.

Revising/Editing Process. Graphic by Payton Hayes.

Querying To No Avail. Graphic by Payton Hayes.

If you are still in the preparation phases of the writing process, consider checking out my Manuscript Basics guide for some quick tips for formatting your manuscript for editing or submission.

How To Find An Agent

When it comes to actually selecting agents to query, you definitely should do your own research. Look into as much as you can find on current releases, popular titles, publisher names, top/mid-tier agents, authors, and trends in your genre. Finding a literary agent for your book is like finding a spouse —it’s a learning process and period of research best conducted by you and there is not one-size-fits-all approach to securing an agent.

PublishersMarketplace.com is the best place to research literary agents; not only do many agents have member pages there, but you can search the publishing deals database by genre, category, and/or keyword to pinpoint the best agents for your work. Some other resources to consider include QueryTracker (free and paid versions) and Duotrope.

If you really prefer to hire someone to find appropriate agents for you to submit to, try Copy Write Consultants.

Consider attending writer’s conventions and getting involved in editorial associations to build connections and organically network with industry professionals. Local writing workshops and bookstore/library events (such as indie author signings/readings) are great ways happen upon literary agents in the as opposed to seeking them out from behind the screen!

Assuming you’re ready to query, there’s a few common materials you’ll likely be asked to provide:

Query Letter - a one-page pitch letter that gives a brief description of your work

Novel Synopsis - a brief summary (typically no more than one or two pages) of your story from beginning to end

Nonfiction formal book proposal - complex proposal documents (Roughly thirty pages worth) to sell nonfiction books to publishers

Novel proposal - your query letter, a synopsis, and perhaps the first chapter. There is not an industry-standard definition of what a novel proposal is.

Sample chapters - the first two to five chapters of your manuscript. (Always start from the beginning of the manuscript; don’t select a middle chapter, even if you think it’s your best.)

Keep these questions in mind when researching agents in your genre:

What’s the agent’s sales track record? Examine their client list and the publishers they’ve recently sold to and determine based on your genre/category and your own sense of author identity if they’d be an appropriate fit for you and your project.

Does their communication with you and other writers inspire confidence?

Do they seem genuinely interested and enthusiastic in you and your project?

Additionally, you may want to keep these optional extra steps in mind if you’re waiting to hear back from queries:

Author media kit

Author/Book website

Author newsletter

New authors with an existing reader base are highly desirable to literary agents and publishers. Putting your work out into the world and building a fan base beforehand can easily give you a leg up over competing writers in your genre. (I’ll have a blog post discussing exactly how to do this in a future post so subscribe to know when that comes out!)

Hook, Book, and Cook Query Sandwich Formula

If the idea querying, marketing, selling, and putting yourself out there makes your skin crawl, then think about it this way: it’s much easier to sell to one person than to ten. If you have an agent, they will do all of the gross publishing heavy lifting so you can focus on writing and connecting with your reader base.

The three main ingredients of a great query sandwich are as follows: the hook, the book, and the cook. To start, the hook is the query —or the pitch, as mentioned earlier. Next, the book is the book itself (what key information about the book should you divulge to the agent on first impression). And lastly, the cook is the writer —you. In keeping with the sandwich metaphor — the “hook” and “cook” sections are the slices of bread and the “book” section is the meat of the sandwich — the slices are the least important part of the query and should take up the least amount of reading time in comparison to the meat.

Hook

You can probably guess why the first section of this metaphor is called the “hook,” but as expected, this section is specifically the pitch to the agent and it’s what “hooks” or demands their attention as a reader. Queries serve to sell the agent your story and the hook’s sole purpose is just that. It’s at most, a few lines to grab the agent’s attention and make them invested in your story and you as a potential client. If the agent reads the hook and finds their interest piqued, they might then read the description of the book and become even more interested to read more, (at which point you’ve “hooked” an agent and opened up connections for potential book deals).

Book

Center around character and work in subtle details about the world rather than info-dumping or over-worldbuilding. Your query isn’t the place for overly flowery vocabulary or backstory either. This section of your query should give the agent just enough of a taste to make them interested in being invested in the story, but not enough to give the plot away or disinterest them before they can even read it.

Be sure to keep storytelling elements character, conflict, and stakes at the forefront of your mind. This section of the query is designed to make the agent care, so show them enough character to make them make a connection and then weave in the conflict and stakes so that not only does the agent now know who the characters are, what they want, and what will happen if they don’t get what they want, but they’re also emotionally invested in the story, which is what will drive them to read it for themselves.

Pro tip: Don’t open the “hook” or “book” sections with rhetorical questions as a cheap grab at the agent’s attention. It’s overdone, comes off as try-hard, and doesn’t deliver the effect as intended so it’s better leaving them out altogether. Here’s an example: “Can Clara save the world and still make it to the school dance by 8? Keep reading to find out!”

Cook

Two women talking at a conference table. Photo by Amy Hirschi.

While the “cook” section of your query is technically about you, don’t give the agent your whole life story or try to cultivate any specific perception of you as a person other than being a writer. This section is your time to showcase your knowledge and experience as a writer and make the agent confident in your abilities. Consider any certifications or degrees you have earned, any workshops, courses, or masterclasses you’ve attended, or any writing clubs or critique groups you’re involved with and how you can use these connections to demonstrate that you’re a capable, competent, writer who is serious about sharing their work with the world.

Additional errors to avoid include mentioning side characters or love interests that do not critically pertain to the prevailing plotline, bogging down descriptions with hard-to-pronounce proper nouns and/or stylistic spellings. Likewise, remember the KISS method —keep it simple, sweetie. Simplicity, clarity, and subtlety are the keys to a great query.

Personalize Your Query

Some optional personalization to your query email includes introductions, genre comparisons, and any additional important/useful information about your novel/series as it pertains to the agents and marketing side of publishing.

One example of a great introduction/connection in action is when a friend of mine attended a writing conference where she unknowingly met her agent. She had never given agents much thought beforehand, but after attending a panel where several literary agents spoke about the book marketing process, she realized she needed to reach out. When she finally completed her book, she was able to break the ice in her query email simply by mentioning they’d attended the same conference and how her advice had helped her.

Don’t include that you’re a first-time or new author; your agent will assume unless you include any relevant published works or previous agents, that you are a new author. The “cook” section of the query is an excellent place to mention relevant writing/marketing experience.

You might also consider providing some comparisons for other books in your genre. Genre comparisons demonstrate to agents that you’re well-read in your niche genre and that you’ve done your research and understand the market you’re writing to. Genre comparisons can also provide a lot of marketing information such as where it might sit on the shelf, what demographic the book might appeal to most, what tones, themes, and tropes are to be expected from a book of any given genre. However, make sure you don’t outright put down other authors or genres when providing comparisons. You’d be surprised how many stories I’ve heard about writers who have included “my book is like so and so’s book but better” when the writer simply means they’ve put an interesting new spin on an old storytelling element.

Additionally, it might be wise to mention that your book is standalone or intended as part of a series. While we might know where the story is headed as the author, it’s ideal for a novel to both be able to stand on its own as well as having series potential, so try not to have your plans set in stone.

Check Agent Guidelines Before Submitting

At the end of the day, every agent conducts business differently and their submission guidelines may vary from one agent to the next. Ensure you’re doing everything in your power to result in a successful query by double checking your agent’s submission guidelines prior to submission. When it comes to personalization, some agents enjoy getting to know more about the writers that send in submissions while others prefer you simply leave it out. Checking guidelines before sending your query through will ensure you don’t push potential agents away by making careless mistakes.

Additionally, if it takes some pressure off, remember that if you simply take time to research your genre and potential agents, proofread and put effort into your query, and ensure that it follows agent guidelines, you will be a step ahead of your competition. Just by chatting with other editors and agents, I’ve learned that the general consensus is that most people just send a query off without a second thought and if you put even just a little extra energy into your query, that time and effort will shine through.

Note: Almost no agent accepts full manuscripts on first contact. (This is what “no unsolicited materials” means when you read submission guidelines.) However, almost all agents will accept a one-page query letter unless their guidelines state otherwise. (If they do not accept queries, that means they are a completely closed market.)

Sleep On Your Query Before Sending It

Once you’ve drafted the perfect query email, save it as a draft in your inbox for at least 24-hrs before sending it. When that time is up, sit down and re-read your query for any missed typos. I personally struggle with this and it’s why I always say everyone can benefit from a second set of eyes, even editors. Grammar, usage, and spelling are unfortunate errors that conceal the quality of your work, so thoroughly proofread your query before hitting that send button. Read it out loud or consider having a mentor or critique partner give it a second set of eyes. If you’re your only proofreader, get some distance from your query by literally stepping away from it and coming back with a fresh perspective so that you can catch any errors you might have missed in your previous revisions. That being said, don’t let this waiting period keep you from hitting send after your 24-hour timer is up. Draft your best query, sleep on it, reread it, put on the finishing touches and hit that send button. I find that if I procrastinate too long, I will actually end up forgetting to send it out. Try to aim for sending out that query after 24 hours and before 72 hours.

Do I Need An Editor Before Querying?

It’s completely up to you and how you feel about the state of your manuscript. Whether or not you hire an editor to polish your manuscript, your submission should be 100% complete and in its best version prior to querying.

Sara Megibow of the Nelson Literary Agency said “In general, too many submissions come through our slush pile that aren’t ready. In my opinion, an editor could have helped many of these books get to the next level. However, I acknowledge that hiring that person is expensive. If you are going to get an editor, don’t skimp - hire someone with credentials and client referrals in the genre of work that you are writing” and suggests that writers “read 3-5 books in your genre, published in the past 2-3 years, preferably by debut authors and published by major publishing houses” if they believe they need professional editing but can’t afford to hire an editor. (Megibow 2021) However, I think this advice is excellent for familiarizing oneself with their given genre. Inversely, you could find agents that represented your favorite books and research their work as well.

Keep Your Query Short & Sweet

Consider closing out your query email with a classic “Thank you for your consideration” and a “Sincerely, YOUR NAME.” Sign your email with your legal name (and if writing under a pen name or pseudonym include “YOUR NAME, writing as YOUR PEN NAME HERE” as well). There is no need to bog down the end of your email with statements such as “I look forward to hearing from you soon,” or “Will send manuscript upon request” because these are automatically assumed as part of the agent intake process. After closing your email, include your contact information and relevant social media links (author/public pages.) Omit these social links if you don’t already have a sizable readership. Don’t include photos, logos, or headshots either.

Simultaneous & Personalized Queries

The writer to agent intake process is inherently an individualized experience and should be treated as such. As writers with a vast overwhelming competition, it’s easy to see how mass-emailing could be tempting since getting a book deal seems like such a numbers game, but it’s more delicate than that. Agents are humans who make connections to stories just like our readers do and thus, you want to ensure you’re doing your research and finding an agent who will be a good fit for you. Querying an agent is a lot like cold emailing in business—it’s harder than most other forms of communication because you typically lack any prior relationship with your audience and you lack non-verbal feedback so you can’t modify your approach in real time, but it doesn’t have to be cold, per se. Much like with editors, writers can and should be encouraged to make a real, lasting connection with your agent and truly, your writing, book sales, and reader base will all benefit from having that genuine writer-agent relationship.

Another way to add some warmth and attention back into your cold queries is to always address agents by their name (never “Dear agent,”) and ensure their name is spelled correctly. Additionally, if you decide to use pronouns to regard your agent, ensure in each instance that the correct pronouns are being used. While you should never mass email a whole list of agents, it is okay to query multiple agents if you’re emailing them individually. Simultaneous queries are perfectly fine as long as you personalize each email for each individual agent. If you query several different agents simultaneously keep track of who you’ve queried and when. If you get any acceptance offers be sure to let the other agents know, especially if multiple agents are interested in your work.

Author Email Address and Professional Headshots

This seems like a no-brainer, but don’t put in all that work to come up with the most amazing query email only to have it flop on the transmission level of the process. As an author, you should have a professional email for all your writing business needs, but if you get a lot of traffic in your inbox already, consider creating an account designated solely for query submission. Ensure the email address itself is self-explanatory, easy to read, write, pronounce, and remember. yournamequeries@gmail.com is simple enough. If you have an author website or own your own domain, then hello@firstnamelastname.com is another great option. For your profile photo, consider a professional business-style headshot photo or a company logo if applicable. If you want to show some personality through your profile picture, try to avoid obscene or offensive imagery.

Leave Rejection Letters On Read

Don’t waste your time by sending responses to rejection emails. It might be tempting ask them to elaborate on any feedback they gave you or to thank them for notice of rejection, but it’s just not necessary at the query stage. Agents can provide incredibly useful feedback when appropriate, but in response to a rejection email is not the place to seek out further feedback. Delete the rejection email, move that agent’s message history to your archives, and move on to the next query email.

Smart Query

Smart querying is the perfect combination of querying best practices, batch querying, and cold email marketing tactics that serves as the single most effective strategy for landing literary agents out of thin air.

Put Together Your Agent Pool

Once you’ve done some market research and you feel like you have a decent grasp on publishers and agents that deal in your genre, start building a pool of agents who you can smart query and query again later. To establish a truly effective agent pool, come up with a mixture of middle and top tier agents as well as agents who typically are known for responding slower/faster to query submissions. It’s generally a good idea to have a healthy mix of different kinds of agents for your genre (as opposed to all top-tier or all quick-responding agents) because you may want options. Likewise, agents that work independently or alongside publishers are good to add to the mix. Additionally, consider querying to agents that represent different demographics that your book may appeal to (such as marginalized or underrepresented communities). A wide variety of stable, established agents as well as emerging agents with potential, is essential to successful and smart querying.

Test Batch Queries

One key element of smart querying is “test batch querying” where like the name suggests, you send out query emails in strategic batches. Unlike just mass-emailing, agents test batch querying allows you to essentially test-run your query before putting all your eggs into baskets. To batch query, choose 3-5 agents from your pool who respond quickly to queries (leave your dream agents out of test batches) and send your query to them first. If you get 1-2 interested responses (they’re requesting the full manuscript for review) then your query is working, and you can open it up to the rest of the agents in your pool. If you find that agents are getting to the manuscript and losing interest, your manuscript may need more attention first.

Pro Tip: When building your pool of agents to query, do your due diligence on various social media platforms. Research your prospective agents on and off the page and ensure your values and work ethic align to avoid any creative differences in the marketing process down the line.

Feedback & Follow-Ups

This may seem obvious, but be sure to take any and all writing-related advice and feedback with a grain of salt, of course. Literary agents, like editors and writers, are all just readers and book lovers at the end of the day. They too are looking for the next greatest story to fall in love with. They make real, meaningful connections to characters and events, so the main goal of a query letter isn’t to sell your story to the agent, but rather to make your story matter to an agent.

After you send out queries, you’ll get a mix of responses, including:

No response at all, which means it’s a rejection. Don’t sweat it—this is normal. Read it, sit with it for a moment, appreciate the opportunity, and move on.

A request for a partial manuscript and possibly a synopsis.

A request for the full manuscript.

If you receive no requests for the manuscript or book proposal, then there might be something wrong with your query. If you succeed in getting your material requested, but then get rejected, there may be a weakness in the manuscript or proposal. You might occasionally receive personalized feedback regarding the state of your manuscript but it’s not standard practice.

Keep in mind that a literary agent’s inbox may be swamped with queries from other writers so it may take them some time to get to your query. If the agent has outline specific query guidlines on their website or social media, look out for estimated response times. If the agent has specified that you can expect to hear back as early as thirty days, then set a reminder to follow up within one week of that estimated response date. If the agent has specified that you can expect a response within two weeks, schedule your follow up for three weeks out. This allows the agent extra time to review your manuscript without being pressured to respond too quickly. A good rule of thumb is one month for independent agents or agents working smaller imprints; for agents working with larger publishers, allow at least three months before sending a follow up. Regardless of the notoriety of the agent, if you don’t recieve a responsee after your first query or your follow up, then its most likely a silent rejection. Don’t send another follow up and don’t send another query to that agent for that specific manuscript later on. Consider it a rejection and move on.

And that’s it for my extensive guide on literary agents and querying! Thanks for checking out my blog post! Did you find any of this helpful? Please let me know and don’t forget to share your experience the comments below!

Bibliography

Copy Write Consultants. “Literary Agent & Publisher Research.” webpage, accessed September 11, 2021.DuoTrope. “Homepage.” Duotrope website , accessed September 11, 2021.Hayes, Payton. “Incomplete/Rough Draft.” Graphic created with Canva, September 11, 2021.Hayes, Payton. “Revising/Editing Process.” Graphic created with Canva, September 11, 2021.Hayes, Payton. “Querying To No Avail.” Graphic created with Canva, September 11, 2021.Hayes, Payton. “Critique Groups & Beta Readers.” Graphic created with Canva, September 11, 2021.Hirschi, Amy. “Woman in teal t-shirt sitting beside woman in suit jacket.” Unsplash photo, (Thumbnail photo) March 5, 2019.Megibow, Sara. “Should You Hire an Editor Before Querying? Agents Weigh In!” Adventures in YA Publishing, July 6, 2014.Publishers Marketplace. “Home.” Publishers Marketplace website, accessed September 11, 2021.QueryTracker. “Home.” QueryTracker website, accessed September 11, 2021.The Directory of Literary Agents. “Find USA Book Agents Looking for New Writers | List of Literary Agents 2022-2023.” Literary Agencies Website, accessed September 11, 2021.

Related Topics

Get Your FREE Story Binder Printables e-Book!NaNoWriMo: 25 Tips To Help You Write A Book In 1 Month! + Free NaNoWriMo Printables20 Tips and Tricks for a Successful Email Newsletter8 Reasons Why Having A Creative Community MattersThe Importance of Befriending Your CompetitionBook Writing 101: How To Come Up With Great Book Ideas And What To Do With ThemBook Writing 101: How To Write A Book (The Basics)Book Writing 101: Starting Your Book In The Right PlaceBook Writing 101: How To Choose The Right POV For Your NovelBook Writing 101: How To Achieve Good Story PacingBook Writing 101: How To Name Your Book CharactersBook Writing 101: How to Develop and Write Compelling, Consistent CharactersBook Writing 101: Everything You Need To Know About DialogueInfo-Dumping in Science Fiction & Fantasy Novels by Breyonna JordanHow To Write Romance: Effective & Believable Love TrianglesHow To Write Romance: Enemies-To-Lovers Romance (That’s Satisfying and Realistic)How To Write Romance: 10 Heart-Warming and Heart-Wrenching Scenes for Your Romantic ThrillerHow To Write Romance: Believable Best Friends-To-LoversHow To Write Romance: The Perfect Meet CuteCheck out my other Author Advice, Marketing, Freelancing, Book Writing 101, How To Write Romance, and How To Get Published posts.

Recent Blog Posts

8 Ways To Level Up Your Workspace And Elevate Your Productivity

Not only is my new workspace such a refreshing place to be in now, but it serves as a fabulous backdrop for my video calls and meetings. If that’s not enough for you, a room this beautiful just makes me so excited to show up and get to work.

Hi readers and writerly friends!

With all of the craziness of the pandemic and most people working from home now, it has become more important now than ever to tailor a special, intentional space for you to do your work and to do it well. Whether you work in an office with a team or from the comfort of your own home, your workspace can have a major impact of the quality of the work you produce and how you feel physically and mentally while you work. Since people are working from home more in 2020 it’s absolutely crucial that you set up your home office for success.

Stay tuned to check out these 8 must-haves for your at-home or in-office workspace so you can always accomplish your best work:

Get the right chair

Making sure you get your best work done starts with a comfortable workspace and a comfortable workspace begins with your seat. A comfy desk chair is an absolute must-have when you’re spending a lot of time seated in deep work and its certainly not an investment you want to skip.

Do some research on what features come with the desk chairs available to you. Consider quality, comfort, aesthetic, and pricing. I’d love to recommend my IKEA Kimstad White Millberget Swivel Chair because it is so comfy! And if you’re wanting something a little fancier, the Furmax Ribbed Office Desk Chair is a great alternative. If you’re looking for a few other chair choices, Forbes has an amazing list of office chairs from best quality to budget options.

Bright and airy workspace. Photo by Adrijana Bozic.

Bright and airy workspace. Photo by Adrijana Bozic.

2. Wallpaper or new paint

Friends, it’s time to ditch the drab drywall and add some color to your space. I recently renovated my home office by painting the walls and changing out the curtains. I went from a horrid creamy yellow color and black curtains (yeah, right? What was I thinking?) and opted for medium gray walls with a beautiful teal accent wall and sheer, teal curtains instead and let me tell you, it has made all the difference. Not only is my new workspace such a refreshing place to be in now, but it serves as a fabulous backdrop for my video calls and meetings. If that’s not enough for you, a room this beautiful just makes me so excited to show up and get to work.

As mentioned, you can add an accent wall if wallpapering or painting all four walls is just too daunting at this time. Removable wallpaper is a fantastic option for experimenting with different aesthetics— just stick it on and peel it off when you’re done.

You can find removeable wallpaper just about anywhere, but I recommend supporting fellow artists on Society6. You can find some unique and amazing wallpaper designs for a special, tailor-made workspace.

Pro tip: If you can’t commit to wallpaper or painting, consider checking out wall hangings and tapestries instead. These are a great way to add in a pop of color to your space in a less-invasive, less-permanent way. Society6 sells artist’s work in tapestries and wall hangings as well.

3. Lighting

It’s no secret that lighting is a big deal both in and out of the content creation world. Whether or not you’re working for someone else or yourself while you work from home, the quality of your work will suffer if you’re not working in the right lighting. Don’t strain your eyes. Good lighting is essential for focus and productivity. Science shows that poor lighting can ultimately impact your mindset—this study from the NIMH has found that light directly impacts mood and learning.

My Chesapeake Bay Pearlized Rain Glass Oil Diffuser. Photo by Payton Hayes.