Info-Dumping in Science Fiction & Fantasy Novels by Breyonna Jordan

Info-dumping occurs when writers provide excessive background information in a single section, potentially overwhelming readers and disrupting the narrative flow. This issue is prevalent in science fiction and fantasy genres due to their complex world-building requirements. Indicators of info-dumping include lengthy paragraphs, minimal action or conflict, and the author's voice overshadowing the characters'. To avoid this, authors should focus on essential details, integrating additional information gradually as the story progresses. This approach keeps readers engaged without inundating them with information, maintaining a robust and immersive setting.

Hi readers and writerly friends!

If you’re new to the blog, thanks for stopping by, and if you’re a returning reader, it’s nice to see you again! For this post, Breyonna Jordan is taking over the blog to tell you all about info-dumping in science-fiction and fantasy novels! Leave her a comment and check out her website and other socials!

Breyonna Jordan loves exploring new frontiers—underground cities, mythical kingdoms, and expansive space stations, to be exact. As a developmental editor, she relishes every opportunity to help world-builders improve their works and learn more about the wonderful world of writing. She enjoys novels that are fresh, far-reaching, and fun and she can’t wait to see your next book on her TBR list.

Breyonna Jordan is a developmental editor who specializes in science-fiction and fantasy.

What is Info-Dumping?

When writing sci-fi or fantasy, there’s a steep curve on how much the audience needs to know—a world of a curve in fact.

You may have pages and pages of elaborate world histories that readers must be filled in on—the current and past ruling monarchs, failed (or successful) uprisings, how natural resources became so scarce in this particular region, or why a military state exists in this country, but not in the surrounding lands.

Alternatively, you may feel the need to include pages of small details concerning the settings and characters your readers are exploring. While it’s important to include specific details in your writing—the reader can’t possibly know that the night sky features four moons unless you convey these details—oftentimes, the excess exposition can be overwhelming to readers.

This info-dumping can be a pervasive problem in fiction, maybe even the problem that stops you from finding an awesome agent or from obtaining a following on Amazon.

So, below I’ve offered some tips for spotting info-dumping, reasons for and the potential consequences of info-dumping, as well as several tips for avoiding the info-dump.

How Do You Identify Info-Dumping In Your Manuscript?

A section of your work may contain info-dumping if you find:

you are skipping lines while reading (Brotzel 2020),

the paragraphs are very long,

there is little action and conflict occurring,

your voice (and not your characters) has slipped in,

that it looks like it was copied directly from your outline

To help you get a better idea of what excessive exposition can look like, here are two examples of info-dumping from the first chapter of a sci-fantasy manuscript I worked on:

“Hawk was guarding the entrance to the cave while Beetle went for the treasure. These were not their real names of course but code-names given to them by their commander (now deceased) to hide their true identities from commoners who may begin asking questions. Very few people in the world knew their true names and survived to speak it. Hawk and Beetle knew each other’s true names but had sworn to secrecy. They were the youngest people on their team. Beetle was seventeen with silver hair and had a talent for tracking. Hawk was twenty-one with brown hair which he usually wore under a white bandana. He was well-mannered and apart from his occupation in burglary was an honest rule-follower. Beetle and Hawk had known each other since they were children and were as close as brothers.”

“It is one of the greatest treasures in the entire world of Forest #7. This was thought only to have existed in legend and theological transcripts. This Staff was powered by the Life Twig, a mystic and ancient amulet said to contain the soul of Wind Witch, a witch of light with limitless powers.”

Why Do Writers Info-Dump and What Impacts Does It Have On Their Manuscripts?

As a developmental editor who works primarily with sci-fi and fantasy writers, I’ve seen that info-dumping can be especially difficult for these authors to avoid because their stories often require a lot of background knowledge and world-building to make sense.

In space operas, for example, there may be multiple species and planetary empires with complex histories to keep track of. In expansive epic fantasies, multiple POV characters may share the stage, each with their own unique backstory, tone, and voice.

Here are some other reasons why world-builders info-dump:

they have too many characters, preventing them from successfully integrating various traits,

they want to emphasize character backstories as a driver of motivation,

their piece lacks conflict or plot, using exposition to fill up pages instead,

they are unsure of the readers ability to understand character goals, motivations, or actions without further explanation,

they want to share information that they’ve researched (Brotzel 2020),

they want readers to be able to visualize their worlds the way they see them

A Hobbit house with wood stacked out front. Photo by Jeff Finley.

Though these are important considerations, info-dumping often does more harm than good. Most readers don’t want to learn about characters and settings via pages of exposition and backstory. Likewise, lengthy descriptions:

distract readers from story and theme,

encourage the use of irrelevant details,

make your writing more confusing by hiding key details,

decrease dramatic tension by boring the reader,

slow the pacing and immediacy of writing,

prevent you from learning to masterfully handle characterization and description

Think back to the examples listed above. Can you see how info-dumping can slow the pace from a sprint to a crawl? Can you spot all the irrelevant details that detract from the reader's experience? Do you see the impact of info-dumping on the author’s ability to effectively characterize and immerse the reader in the scene?

Info-dumping is a significant issue in many manuscripts. Often, it’s what divides the first drafts from fifth drafts, a larger audience from a smaller one, a published piece from the slush pile.

What Techniques Can Be Used to Mitigate Info-Dumping?

That said, below are three practical tips to help you avoid and resolve info-dumping in your science-fiction and fantasy works:

Keep focus on the most important details. You can incorporate further information as the story develops. This will allow readers to remain engrossed in your world without overwhelming them. It will also help you maintain a robust setting in which there’s something new for readers to explore each time the character visits.

Weave details between conflict, action, and dialogue (Miller 2014). This will allow the reader to absorb knowledge about your world without losing interest or becoming confused. An expansive galactic battle presents the perfect opportunity to deftly note the tensions between races via character dialogue and behavior. A sword fighting lesson can easily showcase new technology (Dune anyone?). A conversation about floral arrangements for a wedding can subtlysubtely convey exposition. Just make sure to keep the dialogue conversational and realistic.

Allow the reader to be confused sometimes. Most sci-fi and fantasy readers expect to be a bit perplexed by new worlds in the earliest chapters. They understand that they don’t know anything, and thus expect not to learn everything at once. Try not to worry too much about scaring them off with new vocabulary and settings. They can pick up on context clues and make inferences as the story progresses. handle it. If you’re still concerned about the amount of invented terminology and definitions, consider adding a glossary to the back matter of the book instead.

Of course, this all raises the question…

Is It Ever Okay to Info-Dump?

You might think to yourself, “I want to stop info-dumping, but it’s so difficult to write my novel without having to backtrack constantly to introduce why this policy exists, or why this seemingly obvious solution won’t end the Faerie-Werewolf War.”

If you’re a discovery writer, it might be downright impossible to keep track of all these details without directly conveying them in text which is why I encourage you to do exactly that.

Dump all of your histories into the novel without restraint. Pause a climactic scene to spend pages exploring why starving miners can’t eat forest fruit or how this life-saving magical ritual was lost due to debauchery in the forbidden library halls.

Write it all down…

Foggy woods illuminated by a soft, warm light. Photo by Johannes Plenio.

But be prepared to edit it down in the second, third, or even fourth drafts.

Important information may belong in your manuscript, but info-dumps should be weeded out of your final draft as much as possible.

Additionally, as I mention often, I am a firm disbeliever in the power and existence of writing rules. There are novels I love that use info-dumping liberally and even intentionally (re: Hitchhiker’s Guide to The Galaxy by Douglas Adams). Most classics use exposition heavily as well and they remain beloved by fans old and new.

However, what works for one author may not work for everyone and modern trends in reader/ publisher-preference regard info-dumping as problematic. Heavy reliance on exposition is also connected to other developmental problems, such as low dramatic tension and poor characterization.

If you are intentional about incorporating large swaths of exposition and it presents a meaningful contribution to your work, then info-dumping might be a risk worth taking. If the decision comes down to an inability to deal with description and backstory in other ways then consider reaching out to an editor or writing group instead.

What are some techniques you’ve used to avoid info-dumping in your story? Let us know in the comments!

Bibliography

Finley, Jeff. “Hobbit House.” Unsplash photo, February 28, 2018.

Miller, Kevin.“How to Avoid the Dreaded Infodump.” Book Editing Associates article, April 14, 2014.

Plenio, Johannes. “Forest Light.” Unsplash photo, February 13, 2018.

Related Topics

Book Writing 101: Coming Up With Book Ideas And What To Do With Them

Book Writing 101: How to Develop and Write Compelling, Consistent Characters

25 Strangely Useful Websites To Use For Research and Novel Ideas

Recent Blog Posts

Written by Guest Blogger, Breyonna Jordan. | Last Updated: March 14, 2025.Writing Exercises from Jeff Tweedy's Book, How To Write One Song

Jeff Tweedy's book "How to Write One Song" offers innovative exercises to unlock creativity in songwriting and poetry. One such exercise is the "Word Ladder," which involves selecting a specific profession (e.g., physician) and listing ten associated verbs, followed by ten nouns from your immediate surroundings. By pairing these verbs and nouns in unexpected ways, writers can craft unique phrases that serve as the foundation for poems or lyrics. This method encourages the use of simple, everyday language to create fresh and compelling imagery. Tweedy emphasizes that this exercise is less about producing polished lyrics and more about rediscovering the joy and playfulness inherent in language, helping writers break free from conventional patterns and explore new creative avenues.

Hello, readers and fellow writers! Welcome back to the blog, and if you're new here, thank you for visiting! We’ll be discussing how to write a poem or song from a bunch of common words. By tapping into our subconscious and embracing unpredictability and imperfection, we can craft unique and compelling lyrics.

Why words? Because I believe all words have their own music and along with that music, I believe words contain worlds of words and meanings that are more often than not, locked beneath the surface. Poetry is what happens when words are opened up and those worlds within are made visible, and the music behind the words is heard. (Tweedy 2020, 65)

I first encountered this concept through Logan from vib3.machine on TikTok, who explained Jeff Tweedy’s Word Ladder Method from his book How To Write One Song. It’s called the Word Ladder Method because of the way you write out the words and physically link them together on paper.

Keep The Words Simple

I’m not talking about expanding your vocabulary. I mean, that’s always a nice thing to do in the name of self-improvement, but fancy, multisyllabic words aren’t going to make a lyric better.They’re very often the thing that breaks the spell being cast by the melody being cast when I listen to music….In fact, I would say that most of my favorite songwriters consciously stick to common, simple, and precise language, but they don’t use it in a common and simple way within a song or melody. (Tweedy 2020, 68-9)

He gives John Prine as an example of someone who uses concise, simple, language effectively, that he “didn’t use a log of big words or flowery language and when he did, he always stayed true to the song and what needed to be said over any desire to make himself sound smart or poetic.” (Tweedy 2020, 69)

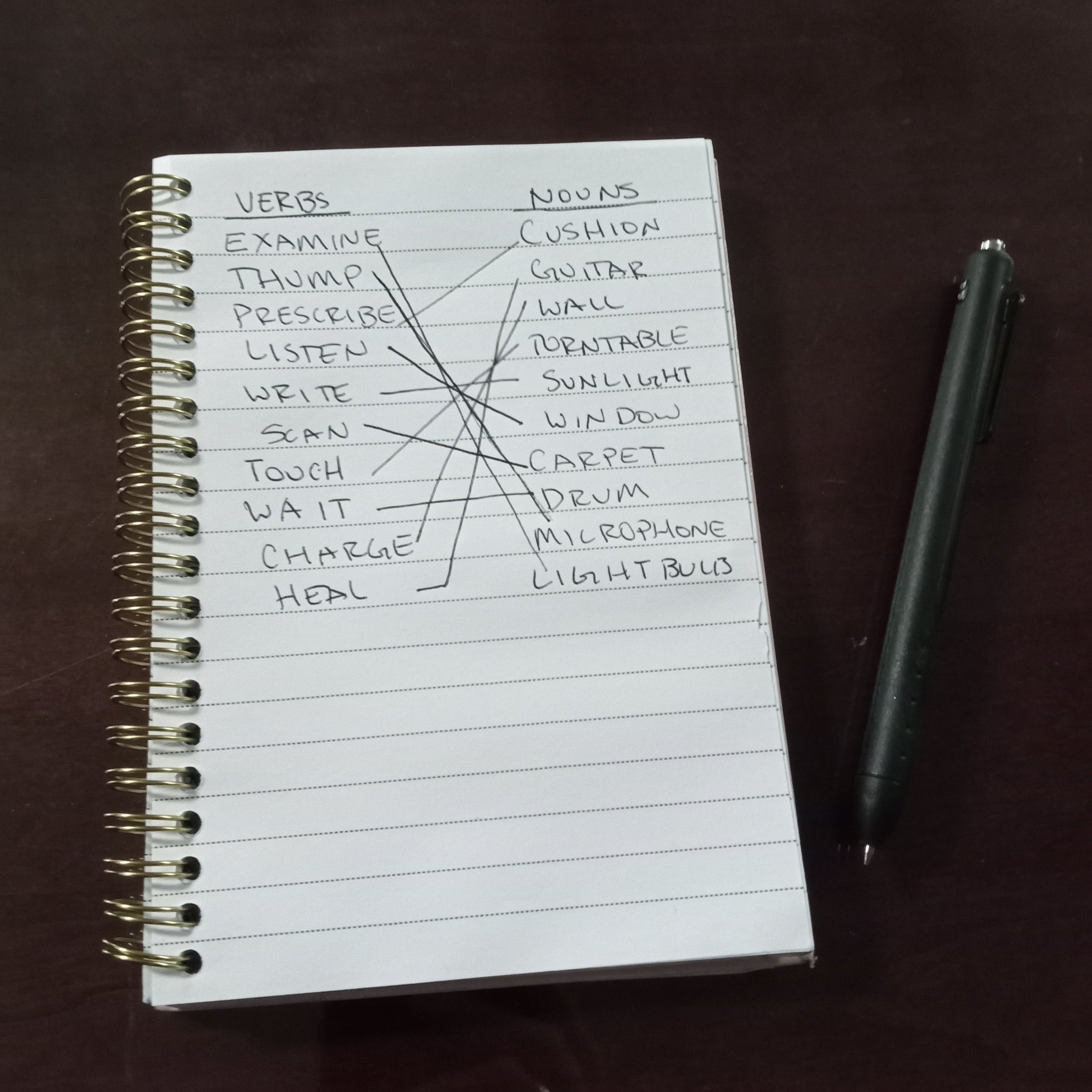

Word Ladder: Verbs and Nouns

The 6 Steps For Songwriting Using The Word Ladder

Step 1: Come up with a label or word for a specific job

Step 2: List out 10 Verbs to describe the label or job

Step 3: List out 10 nouns you currently see in the space around you

Step 4: Connect the two sets of words in a way is unexpected

Step 5: Write a poem with these connections

Step 6: Rearrange and edit the lines to your liking

Jeff Tweedy’s Word Ladder

Step 1: Come up with a label or word for a specific job.

Tweedy selected 'physician' for his example, listing ten verbs associated with a physician and ten nouns from objects within his line of vision.

Step 2: List out 10 Verbs to describe the label or job

Examine

Thump

Prescribe

Listen

Write

Scan

Touch

Wait

Charge

Heal

Step 3: List out 10 nouns you currently see in the space around you

Cushion

Guitar

Wall

Turntable

Sunlight

Window

Carpet

Drum

Microphone

Lightbulb

Step 4: Connect the two sets of words in a way is unexpected.

Examine→ Lightbulb

Thump→ Microphone

Prescribe→ Cushion

Listen→ Window

Write→ Sunlight

Scan→ Carpet

Touch→ Turntable

Wait→ Drum

Charge→ Wall

Heal→ Guitar

Step 5: Write a poem with these connections.

“Now take a pencil and draw lines to connect nouns and verbs that don’t normally work together. I like to use this exercise, not so much to generate a set of lyrics but to remind myself of how much fun I can have with words when I’m not concerning myself with meaning or judging my poetic abilities.” (Tweedy 2020, 73)

Jeff Tweedy’s first draft:

the drum is waiting

by the window listening

where the sunlight writes

on the cushions

prescribed

thump the microphone

the guitar is healing

how the turntable is touched

charging in the wall

while one lightbulb examines

and scans the carpet (Tweedy 2020, 73-4)

I find it almost always works when I’m finding a need to break out of my normal, well-worn paths of language. (Tweedy 2020, 74)

Below is Tweedy’s revision of the poem. He says, you don’t have to use every one of the verbs and nouns or put any restrictions on your writing at this point. The goal of this exercise is to warm up your creative muscles.

Tweedy’s revised poem:

The drum is waiting by the windowsill

Where the sunlight writes its will on the rug

My guitar is healed by the amp charging the wall

And that's not all, I’m always in love (Tweedy 2020, 74)

That’s still a little awkward, but it's enough to jumpstart my brain to where words and language have my full attention again. (Tweedy 2020, 75)

Logan’s (Vib3.machine) Word Ladder

Step 1: Come up with a label or word for a specific job.

The word Logan picked for his example was “astronaut.” He listed out ten verbs to describe an astronaut and then ten nouns from objects in his room.

Step 2: List out 10 Verbs to describe the label or job.

Explore

Discover

Float

Wait

Voyage

Travel

Learn

Fly

Land

Journey

Step 3: List out 10 nouns you currently see in the space around you.

Basket

Letters

Books

Art

Kitchen

Camera

Floor

Watch

Fan

Bike

Step 4: Connect the two sets of words in a way is unexpected. In his captions, Logan said, “Having your subconscious constantly finding creative unique phrases while you aren’t actively TRYING is super powerful. It’s a habit [I’]m [trying] to develop.” (00:45-1:00)

Logan’s word ladder. Photo by Payton Hayes.

Logan connected his verbs and nouns like this:

Explore → Basket

Discover→ Kitchen

Float→ Floor

Wait→ Fan

Voyage→ Books

Travel→ Letters

Learn→ Bike

Fly→ Watch

Land→ Art

Journey→ Camera

Step 5: Write a poem with these connections. Don’t worry if it still doesn’t make sense. Right now, we’re just writing; we’ll edit it soon!

Logan says in regard to lyric writing, to make it as conversational as possible because it’s more relatable. (Logan 2022, 1:30-1:45)

Here was the poem he came up with from those connections:

I explored your basket

And discovered us in the kitchen

We floated on the floor

And waited next to the fan

You voyaged through this book

And traveled every letter

So I can learn to bike

And fly through this watch

You landed in my art

And the camera we journeyed (Logan 2022, 2:36-2:50)

He said, “I know this sounds like nonsense, but we just wrote something without thinking about it.” (Logan 2022, 2:30-2:35)

Step 6: Rearrange and edit the lines to your liking. For full-length songs and longer poems, continue the process with each stanza. Consider sticking with a common theme, for your first 10 words each time you start the process within one poem or song, but change the words you use for this process with each stanza. Try to avoid unintentional repetition. For poems, see if you can create a rhyme scheme with the words and themes present and make use of the elements of poetry.

I Wrote A Poem Using The Word Ladder Exercise

I was substituting for a high school drama teacher when I tried this exercise so, you might notice a theme.

Step 1: Come up with a label or word for a specific job

I picked “Actress”

Step 2: List out 10 Verbs to describe the label or job

Perform

Practice

Dance

Project

Articulate

Memorize

Act

Pantomime

Smile

Transform

Step 3: List out 10 nouns you currently see in the space around you

Podium

Mirror

Pen

Curtain

Piano

Spotlights

Screen

Tape

Carpet

Garbage

My word ladder. Photo by Payton Hayes.

Step 4: Connect the two sets of words in a way is unexpected

Perform→ Spotlights

Practice→ Tape

Dance→ Carpet

Project→ Podium

Articulate→ Piano

Memorize→ Spotlights

Act→ Garbage

Pantomime→ Mirror

Smile→ Curtain

Transform→ Screen

Step 5: Write a poem with these connections

The performance begins with the spotlights

The practice tape is peeling up as I

Dance across the carpet

My teacher projects from the podium and

The piano’s keys articulate a melody

I’ve memorized my position beneath the spotlights

Inside, I hope my acting isn’t total garbage

My classmate pantomimes in the mirror

I plaster on a smile as the curtain opens

We transform from stage to screen

Step 6: Rearrange and edit the lines to your liking

The performance begins with the spotlights

The practice tape is peeling up from the stage

Dancing on the painted wood is nothing like the carpet in our classroom.

For a breath, I think back to rehearsal —the director projecting ques from the podium

The pianos keys articulate the melody of the opening coda

I’ve memorized my lines a million times beneath these spotlights

And still, I hope that my acting isn’t total garbage

The other actors pantomime one another like reflections in mirrors

I plaster on a smile as the curtain opens

We transform from students on a stage to actors on a screen

Here is my final poem:

ACTRESS

The performance begins with the spotlights

The practice tape is peeling up from the stage

Dancing on the painted wood is nothing like the carpet in our classroom.

For a breath, I think back to rehearsal —the director projecting cues from the podium

The pianos keys articulate the melody of the opening coda

I’ve memorized my lines a million times beneath these spotlights

And still, I hope that my acting isn’t total garbage

The other actors pantomime one another like reflections in mirrors

I plaster on a smile as the curtain opens

We transform from drama students in a classroom to actors on a stage

As you can see this process is easy, effective, and creatively freeing. It takes the pressure of your shoulders to create something perfect, especially with the first draft. Having this skill is a great resource for writers both new and seasoned because it gets the words out of our heads and onto the paper and it gives us something to work with. You can edit a bad page but you can’t edit a blank page.

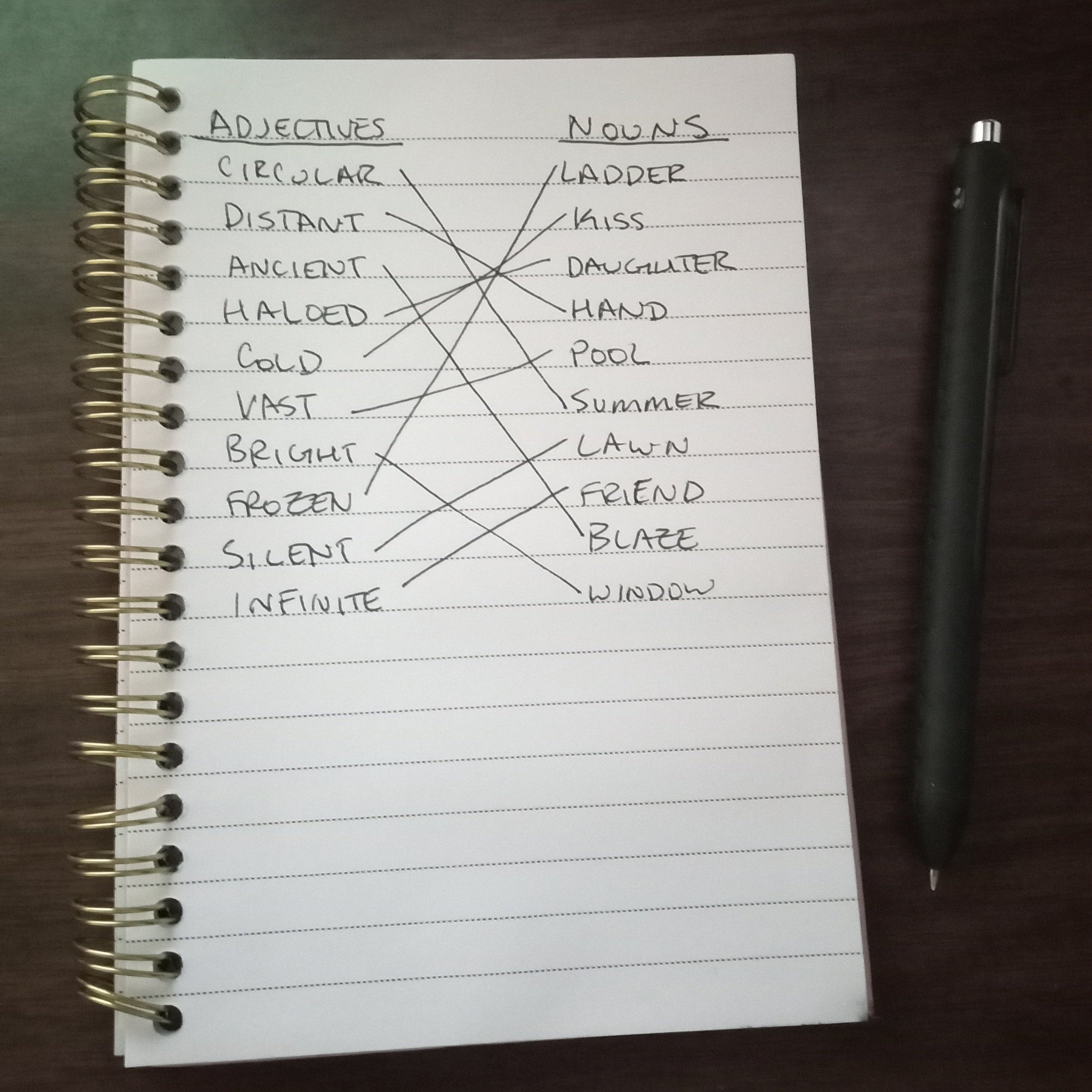

Exercise 4: Word Ladder Variation (Using Adjectives)

Don’t let adjectives make you think you’re being poetic. An “impatient red fiery orb loomed in the whiskey-blurred, cottony-blue sky is rarely going to hit me anywhere near as hard as “I was drunk in the day.”...Of course, it’s strange how adding words to paint a clearer, more specific image often muddies the image you’re trying to expose. The problem is when they are used to spice up a vague verb or noun instead of replacing that with precise language….”I was extremely frightened by the very large man behind the counter” versus “I was petrified by the colossus working the register. (Tweedy 2020, 86)

Step 1: Come up with a location

Step 2: List out 10 adjectives to describe that location

Step 3: List out 10 nouns in your line of vision or that pop into your head (and aren’t related to the location you picked)

Step 4: Connect the two sets of words in a way is unexpected

Step 5: Write a poem with these connections

Step 6: Rearrange and edit the lines to your liking

Step 1: Come up with a location

Tweedy selected “outer space” for his location.

Step 2: List out 10 adjectives to describe that location

Circular

Distant

Ancient

Haloed

Cold

Vast

Bright

Frozen

Silent

Infinite

Step 3: List out 10 nouns in your line of vision or that pop into your head (and aren’t related to the location you picked)

Ladder

Kiss

Daughter

Hand

Pool

Summer

Lawn

Friend

Blaze

Window

Jeff Tweedy’s word ladder variation. Photo by Payton Hayes.

Step 4: Connect the two sets of words in a way is unexpected

Circular→ Summer

Distant→ Hand

Ancient→ Blaze

Haloed→ Daughter

Cold→ Kiss

Vast→ Pool

Bright→ Window

Frozen→ Ladder

Silent→ Lawn

Infinite→ Friend

Step 5: Write a poem with these connections

Tweedy’s poem came out as:

there is a distant hand

on a frozen ladder

climbing through

a bright window

a vast pool waiting

beside a silent lawn

where a daughter haloed

lives a circular summer

one cold kiss

from an infinite friend

away from an ancient blaze (Tweedy 2020, 87)

It’s not a perfect poem, but it took me only about fifteen minutes to complete, and I really do enjoy some of the imagery that emerged. I actually found a few bits of language that I’ve been looking for to complete a song I’ve been working on. (Tweedy 2020, 87)

Exercise 2: Steal Words From A Book

This is the second writing exercise in Tweedy’s book. It’s a bit more free-form than the first exercise and can be helpful for getting you used to working with lyric fragments. (Tweedy 2020, 77)

Step 1: If you have a melody, keep it at the forefront of your mind as you read

Step 2: Skim over a page and see what words jump out at you

Step 3: Highlight the words that strike you

Step 4: Keep going until you have a collection of words that sound right with your melody

Step 5: Use an anchor word if one strikes you and pair other melodic words you find with it

Tweedy explains that this process helps put his ego securely in the backseat and forces him to surrender to a process that puts language/words in front of his creative path and he feels free to find them as though they’ve come from somewhere else. He feels more free to react with surprise and passion or cold indifference than he is able to when his intellect begins treating his lyrical ideas like precious jewels. (Tweedy 2020, 78)

He recommends using anchor words if any jump out at you and to find words that go well together sonically. He uses “catastrophe” as an anchor word and uses it to create the following lines:

wouldn’t you call it a catastrophe

when you realize you’d rather be

anywhere but where you are

and far from the one you want to see? (Tweedy 2020, 79)

Tweedy advises “overdoing it” in terms of coming up with lyrics you like. “Coming up with more than you need is almost never going to make a song worse. Sometimes every good line doesn’t make it into the song you’re working on. But that doesn’t mean you have to throw those lines away. I go back and look at the pages of lyrics I’ve written with this process…and find things I love, even ones I never used, frequently. It helps for there to be some length of time between when they were written and revisited, especially for it to be long enough for the initial melody to have faded. At this point you’re not committing yourself to anything. You’re just creating building blocks. (Tweedy 2020, 79-80)

Exercise 3: Cut-Up Techniques

Grab something you’ve been working on and write it all down on a legal pad. Or if you have access to a printer, print it out double-spaced… The easiest cutting strategy is line by line, but word by word or phrase by phrase can provide equally interesting results. Once you’ve cut up your text, you can either put the strips in a hat or turn them over and pull each line/word/phrase randomly. Then scan your chosen poem construction for unexpected surprises. (Tweedy 2020, 81)

Tweedy says he almost always finds “at least one newly formed phrase or word relationship” that “moves” him or makes him “smile.” (Tweedy 2020, 81)

“Another way to use your cut-up strips is to forget about trying to make random associations and just use them as moveable modules of language. It’s always fascinating to me how much more alive lines I’ve written become when I’m able to have a simple tactile experience reorganizing the order and syntax of the lines and phrases.” (Tweedy 2020, 81-2)

Tweedy provides a comparison of the initial order and finalized order of a set of lyrics from his song, “An Empty Corner”

Version 1:

In an empty corner of a dream

My sleep could not complete

Left on a copy machine

Eight tiny lines of cocaine (Tweedy 2020, 82)

Version 2:

Eight tiny lines of cocaine

Left on a copy machine

In an empty corner of a dream

My sleep could not complete (Tweedy 2020, 83)

“[The second] version is so much more powerful and better overall that I can’t believe I ever tried to sing these lyrics in any other order…Take the time to play with your words. Allow yourself the joy of getting to know them without being precious about directing everything they are trying to say.” (Tweedy 2020, 83)

Exercise 5: Have A Conversation

In Chapter 12 of Tweedy’s book, he advises trying another liberating writing exercise. He says to record yourself and someone else having a conversation to see what lyrics can emerge from common conversational language. He shows two examples of this exercise in action and it’s actually brilliant. For the sake of brevity, I’m only including the steps for this exercise but I highly recommend you try it.

Step 1: Record a conversation or rewrite it as accurately to life as possible

Step 2: Take the important and surprising snippets from the conversation

Step 3: Arrange those snippets to amplify or give them new meaning

Step 4: Read it aloud

Step 5: Rearrange and edit as necessary

Other Writing Exercises In Tweedy’s Book

Some other exercises Tweedy recommends in his book include playing with rhymes (in an unexpected and new way) and pretending to be someone else and channeling their essence when writing songs or poems, which takes the pressure to be vulnerable and perfect off the writer’s shoulders. He also recommends songwriters collect pieces of music, either in the form of mumbled songs, hummed tunes, instrumentals you play yourself or digitally, or music from other artist’s songs and advises songwriters to learn other people’s songs like the back of your hand, so you can take them apart and create something new with those parts.

Additionally, he advises writers to “steal” elements of songs such as themes, lyric fragments, chord progressions, and melodies from existing songs and make them your own. He strongly advises writers to loosen their judgment and allow the creativity to flow freely.

He explains writer’s block as he sees it and provides four conflicting tips for combatting the “stuck” feeling that comes with being creatively blocked: “1) start in the wrong place, 2) start in the right place, 3) put it away, and 4) don’t put it away.” (Tweedy 2020, 144-49) By all of this, he means rearrange song parts until they sound like a good fit for that part of the song, work on fragments or start from the end if the beginning is stumping you, walk away from the piece if its just not working and “keep punching” until you push through to the lyrics you’re looking for.

That’s it for my guide, on writing a song or poem using writing exercises from Jeff Tweedy’s book, How To Write One Song. I hope you enjoyed it and that this process inspired you to try this in your own writing. If you do try this method, post your work in the comments below so I can see how it helped you! Make sure to check out Jeff Tweedy’s book and Vib3.machine’s TikTok for more information on songwriting! Thanks for reading!

Bibliography

Hayes, Payton. “How To Write One Song by Jeff Tweedy.” Thumbnail Image, November 6, 2022.

Hayes, Payton. “Jeff Tweedy’s word ladder.” November 6, 2022.

Hayes, Payton. “Logan’s word ladder.” November 6, 2022.

Hayes, Payton. “My word ladder.” November 6, 2022.

Hayes, Payton. “Jeff Tweedy’s word ladder variation.” November 6, 2022.

Related Topics

“Twenty Little Poetry Projects” Writing Exercise by Jim Simmerman

Screenwriting For Novelists: How Different Mediums Can Improve Your Writing

Experimentation Is Critical For Creators’ Growth (In Both Art and Writing)

Why Fanfiction is Great Writing Practice and How It Can Teach Writers to Write Well

How To Write Poems With Artificial Intelligence (Using Google’s Verse by Verse)

Recent Blog Posts

Written by Payton Hayes | Last Updated: March 14, 2025. Book Writing 101 - How To Chose The Right POV For Your Novel

The point of view is the lens through which your readers connect with your characters and having the right POV can make your story while having the wrong point of view can certainly break it. There’s no real wrong or right here, but sometimes certain viewpoints just make sense for certain stories. We’re going to look at the definition of POV, the importance of POV, the four different POV’s, what POV’s are popular in what genres, how to know when the POV you’re using is right/wrong for your novel, the top POV mistakes new writers make, and how to execute POV well so that it acts as the perfect vehicle through which you tell your story.

A stack of books with different points of view. Photo by Payton Hayes.

Hi readers and writerly friends!

This week in Freelancing, we’re discussing how to choose the right POV—Point of View—for your book. This refers to not only the way your story is told but also who is telling your story. The point of view is the lens through which your readers connect with your characters and having the right POV can make your story while having the wrong point of view can certainly break it. There’s no real wrong or right here, but sometimes certain viewpoints just make sense for certain stories. We’re going to look at the definition of POV, the importance of POV, the four different POV’s, what POV’s are popular in what genres, how to know when the POV you’re using is right/wrong for your novel, the top POV mistakes new writers make, and how to execute POV well so that it acts as the perfect vehicle through which you tell your story.

Point of View Definition

Point of view is (in fictional writing) the narrator's position in relation to a story being told, or position from which something or someone is observed.

The point of view, or POV, in a story is the narrator’s position in the description of events, and comes from the Latin phrase, “punctum visus,” which literally means point sight. The point of view is where a writer points the sight of the reader.

Note that point of view also has a second definition.

In a discussion, an argument, or nonfiction writing, a point of view is a particular attitude or way of considering a matter. This is not the type of point of view we’re going to focus on in this blog post, (although it is helpful for nonfiction writers, and for more information, I recommend checking out Wikipedia’s neutral point of view policy).

I also enjoy the German word for POV, which is Gesichtpunkt, which can be translated as “face point,” or where your face is pointed. How’s that for a great visual for point of view?

Note too that point of view is sometimes called “narrative mode.”

Why is Point of View so Important?

So, why does point of view matter so much? Point of view filters everything in your story. Every detail, event, piece of dialogue, person, and setting is observed through some point of view. If you get the point of view wrong, your whole story will suffer for it.

One writing mistake I see often in my editing work is when writers use the wrong point of view for their stories. As the writer, it can sometimes be hard to tell when your story is written in the wrong point of view, but for readers it sticks out like a sore thumb. These mistakes are easily avoidable if you’re aware of them and I’ll go over just how to do that later on in this blog post.

The four different types of POV’s

First person point of view. First person is when “I” am telling the story. The character is in the story, relating his or her experiences directly.

Second person point of view. The story is told to “you.” This POV is not common in fiction, but it’s still good to know (this POV is common in nonfiction, such as blog posts like this one).

Third person point of view, limited. The story is about “he” or “she.” This is the most common point of view in commercial fiction. The narrator is outside of the story and relating the experiences of a character.

Third person point of view, omniscient. The story is still about “he” or “she,” but the narrator has full access to the thoughts and experiences of all characters in the story.

First Person Point of View

In first person point of view, the narrator is in the story and is the one who is telling the events he or she personally experiencing. The easiest way to remember first person, is that the narrative will use first-person pronouns such as My, Me, Myself, and I. First person point of view is one of the most common POVs in fiction writing. What makes this point of view so interesting and challenging, is that all of the events in the story are experienced through the narrator and explained in his or her own unique voice. This means first person narrative is both biased and incomplete, and it should be.

Some things to note about first person point of view:

First person narrative is mostly unique to writing. While it does appear in film and theater, first person point of view is typically used in writing rather than other art mediums. Voiceovers and mockumentary interviews like the ones in The Office, Parks and Recreation, Lizzie McGuire, and Modern Family provide a level of first-person narrative in third person film and television.

First person point of view is limited. First person narrators observe the story from a single character’s perspective at a time. They cannot be everywhere at once and thus cannot get all sides of the story. Instead, they are telling their story, not necessarily the story.

First person point of view is biased. In first person novels, the reader almost always sympathizes with a first-person narrator, even if the narrator turns out to be the villain or is an anti-hero with major flaws. Naturally, this is why readers love first person narrative, because it’s imbued with the character’s personality, their unique perspective on the world. If I were recounting a story from my life, my own personal worldview would certainly color that story, whether I was conscious of it or not. First-person narrators should exhibit the same behaviors when telling their stories.

Some novelists use the limitations of first-person narrative to surprise the reader, a technique called unreliable narrator. You’ll notice this kind of narrator being used when you, as the reader or audience, discover that you can’t trust the narrator.

For example, Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl pits two unreliable narrators against one another. Each relates their conflicting version of events, one through typical narration and the other through journal entries. Another example is Rosie Walsh’s Ghosted, where the main narrator conveniently leaves out some key information about herself and her missing lover which could change reader opinion of her, had it been presented earlier in the story. Once it finally is presented, readers can’t help but feel they were deceived by the narrator and wonder who they should trust at the end of the story.

Other Interesting Uses of First-Person Narrative:

Harper Lee's novel To Kill a Mockingbird is told from Scout's point of view. However, while Scout in the novel is a child, the story is told from her perspective as an older woman reflecting on her childhood.

The classic novel Heart of Darkness, by Joseph Conrad, is actually a first-person narrative within a first-person narrative. The narrator recounts verbatim the story Charles Marlow tells about his trip up the Congo river while they sit at port in England.

Many first-person novels feature the most important character as the storyteller. However, in novels such as F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby, the narrator is not Jay Gatsby himself but Nick Carroway, a newcomer to West Egg, New York.

"I lived at West Egg, the — well, the less fashionable of the two, though this is a most superficial tag to express the bizarre and not a little sinister contrast between them. My house was at the very tip of the egg, only fifty yards from the Sound, and squeezed between two huge places that rented for twelve or fifteen thousand a season. The one on my right was a colossal affair by any standard — it was a factual imitation of some Hotel de Ville in Normandy, with a tower on one side, spanking new under a thin beard of raw ivy, and a marble swimming pool and more than forty acres of lawn and garden. It was Gatsby's mansion. Or rather, as I didn't know Mr. Gatsby it was a mansion inhabited by a gentleman of that name. My own house was an eye-sore, but it was a small eye-sore and it had been overlooked, so I had a view of the water, a partial view of my neighbor's lawn and the consoling proximity of millionaires — all for eighty dollars a month."

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

2 Major mistakes I often see writers make when using First Person Point of view:

The narrator isn’t likable. Your protagonist doesn’t have to be perfect, and in fact, that’s generally frowned upon because people want to connect with characters and no real human is perfect. They don’t have to be a cliché hero nor do they even have to be good. However, your main protagonist must be interesting. Your audience won’t stick around for even a hundred pages if they have to listen to a character they just don’t enjoy. This is one reason anti-heroes make fantastic first person narrators —they may not be perfect, but they’re almost always interesting.

The narrator tells but does not show. We’ve heard this phrase “show, don’t tell” thrown around a lot in the writing community, and while it’s often used as a buzz phrase, and requires some elaboration to make sense, it’s especially true with first person narration. Don’t spend too much time in your character’s head, explaining what he or she is thinking and how they feel about the situation. The reader’s trust relies on what your narrator does, not what they think about doing. It’s all about action. To build on that, first person is the absolute closest a narrator can get to a reader’s personal experience—by that, I mean readers will make the most connection and feel the most represented by first person narration, as long as it is done correctly. Everything the narrator sees, feels, tastes, touches, smells, hears, and thinks should be as imaginable as possible for your reader. It needs to be the difference between looking at a photo of a field of wildflowers and actually standing in the field (mentally.)

Second Person point of view

While not often used in fiction —it is used regularly in nonfiction, web-based content, song lyrics, and even video games — second person POV is good to understand. In this point of view, the narrator relates the experiences using second person pronouns such as “you” and “your.” Thus, you become the protagonist, you carry the plot, and your fate determines the story.

Here are a few great reasons to use second person point of view:

It pulls the reader into the action of the story

It makes the story more personal to the reader

It surprises the reader because second person is not as commonly used in fiction

It improves your skills as a writer

Some novels that use second person point of view are:

Remember the Choose Your Own Adventure series? If you’ve ever read one of these novels where you get to decide the fate of the character, you’ve read second person narrative.

Similar to the Choose Your Own Adventure series, there was a really interesting and unique interactive game based on Josephine Angelini’s Starcrossed Trilogy that could be played from the Figment website. It was based in Angelini’s modern-day world and surrounded the main character Helen Hamilton, who is gradually revealed to be a modern-day Helen of Troy. The game was a playable maze that took place in Hamilton’s dreams —she would wake up each night after having the same nightmare of being trapped in an endless labyrinth.

The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern takes place primarily in third person but every few chapters, it shifts to second person which pulls the reader right into the story.

The opening of The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern:

ANTICIPATION

The circus arrives without warning.

No announcements precede it, no paper notices on downtown posts and billboards, no mentioned or advertisements in local newspapers. It is simply there, when yesterday it wasn’t.

The towering tents are striped in white and black, no golds and crimsons to be seen. No color at all, save for the neighboring tree and the grass of the surrounding fields. Black-and-white striped and sizes, with and elaborate wrought-iron fence encasing them in a colorless world. Even what little ground is visible from outside is black or white, painted or powdered, or treated with some other circus trick.

But it is not open for business. Not just yet.

Within hours everyone in town has heard about it. By afternoon, the news has spread several towns over. Word of mouth is a more effective method of advertisement than typeset words and exclamation points on paper pamphlets or posters. It is impressive and unusual news, the sudden appearance of a mysterious circus. People marvel at the staggering height of the tallest tents. They stare at the clock that sits just inside the gates that no one can properly describe.

And the black sigh painted in white letters that hangs upon the gates, the one that reads:

Opens at nightfall

Closes at dawn

“What kind of circus is only open at night?” people ask. No one has a proper answer, yet as dusk approaches there is a substantial crowd of spectators gathering outside the gates.

You are amongst them, of course. Your curiosity got the better of you, as curiosity is wont to do. You stand in the fading light, the scarf around your neck pulled up against the chilly evening breeze, waiting to see for yourself exactly what kind of circus only opens once the sun sets.

The ticket booth clearly visible behind the gates is closed and barred. The tents are still, save for when they ripple ever so slightly in the wind. The only movement within the circus is the clock that ticks by the passing minutes, if such a wonder of sculpture can even be called a clock.

The circus looks abandoned and empty. But you think perhaps you can smell caramel wafting through the evening breeze, beneath the crisp scent of the autumn leaves. A subtle sweetness at the edges of the cold.

The sun disappears completely beyond the horizon, and the remaining luminosity shifts from dusk to twilight. The people around you are growing restless from waiting, a sea of shuffling feet, murmuring about abandoning the endeavor in search of someplace warmer to pass the evening. You yourself are debating departing when it happens.

First there is a popping sound. It is barely audible over the wind and conversation. A soft noise like a kettle about to boil for tea. Then comes the light.

All over the tents, small lights begin to flicker, as though the entirety of the circus is covered in particularly bright fireflies, the waiting crowd quiets as it watches this display of illumination. Someone near you gasps. A small child claps his hands with glee at the sight.

When the tents are all aglow, sparkling against the night sky, the sign appears.

Stretched across the top of the gates, hidden in curls of iron, more firefly-like lights flicker to life. The pop as they brighten, some accompanies by a shower of glowing white sparks and a bit of smoke. The people nearest to the gates take a few steps back.

At first, it is only a random pattern of light. But as more of them ignite, it becomes clear that they are aligned in scripted letters. First a C is distinguishable, followed by more letters. A q, oddly, and several e’s. When the final bulb pops alight, and the smoke and sparks dissipate, it is finally legible, this elaborate incandescent sign. Leaning to your left to gain a better view, you see that it reads:

Le Cirque des Rêves

Some in the crowd smile knowingly, while others frown and look questioningly at their neighbors. A child near you tugs on her mother’s sleeve, begging to know what it says.

“The Circus of Dreams,” comes the reply. The girl smiles delightedly.

Then the iron gates shudder and unlock, seemingly by their own volition. They swing outward, inviting the crowd inside.

Now the circus is open.

Now you may enter.

—Erin Morgenstern, The Night Circus

There are also many short stories that use second person, and writers such as William Faulkner, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Albert Camus that played with this point of view.

2 Major mistakes I often see writers make when using Second Person Point of view:

Breaking the fourth wall completely. Some writers, such as Shakespeare often broke the first wall within their writing. However, this must be done correctly, otherwise, it yanks the reader straight out of the story and leaves them feeling distracted and often causes them to cringe at the poorly executed technique. In the plays of William Shakespeare, a character will sometimes turn toward the audience and speak directly to them. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Puck says:

“If we shadows have offended, think but this, and all is mended, that you have but slumbered here while these visions did appear.” —William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Breaking the fourth wall is a technique of speaking directly to the audience or reader (the other three walls being the setting of the story/play.) Another way of looking at it is this: it’s a way the writer can briefly use second person point of view in a first or third person narrative.

Unintentionally alternating between first and second person. This only works if it was done intentionally and makes sense within the context of the story. I am interweaving first and second person in my blog post because I, the writer, am sharing my personal experience with you, the reader. This works and is most common in web-based content, social media or non-fiction, and it can be tricky to pull off in fiction writing.

Third person point of view

In third person point of view, the narrator is outside of the story and is relating the experiences of a character. The central character is not the narrator and in face, the narrator is not present in the story at all. The simplest way to understand third person narration is that it uses third-person pronouns, such as he/she, his/her, they/theirs.

There are two subtypes of third person point of view:

Third person omniscient – The narrator has full access to all the thoughts and experiences or all the characters in the story. This subtype of third person narration is not limited by a single viewpoint.

Examples of Third Person Omniscient:

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

The Raven Boys by Maggie Stiefvater

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel (Read my Review Here)

Atonement by Ian McIwan

Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

Atonement is a 2001 British metafiction novel written by Ian McEwan. Set in three time periods, 1935 England, Second World War England and France, and present-day England, it covers an upper-class girl's half-innocent mistake that ruins lives, her adulthood in the shadow of that mistake, and a reflection on the nature of writing. McIwan makes clever use of story order, tense, and third person POV to tell a story from multiple points in time, and due to its nature as a metafiction, the story recognizes itself as a work of fiction that likely could not be achieved in any other point of view.

Metafiction is a form of fiction which emphasizes its own constructedness in a way that continually reminds readers to be aware that they are reading or viewing a fictional work.

Third person limited – the narrator has only some, if any, access to the thoughts and experiences of the character in the story, often just to one character. It is not uncommon for dialogue to be the primary mode of storytelling in this point of view because if the narrator has little to no access to the inner thoughts and feelings of the characters, the reader might not get that information from a third person limited narrator.

Some examples of third person limited:

Game of Thrones by George R.R. Martin

Ulysses by James Joyce

1984 by George Orwell

Should you use third person omniscient or third person limited?

The distinction between third person limited and omniscient point of view is unclear and somewhat ineffectual.

Complete omniscience in novels is rate—its almost always limited in one way or another—if not because the human mind isn’t comfortable/capable of handling all of the thoughts and emotions of multiple people at once, then it’s because most writers prefer not to delve that deep into each character anyways.

To determine which subtype of third person point of view you should use in your story, consider this:

How omniscient does your narrator need to be? How deep are you going to go into your character’s minds? How important is it to the story’s pacing, plot, and characterization that you reveal everything and anything they feel or thing at anytime? If its not absolutely necessary, consider leaving some parts out in order to build intrigue in your readers.

2 Major mistakes I often see writers make when using Third Person Point of view:

Blurring the line between omniscient and limited. This happens all the time because writers don’t fully understand the very, very thin line between the two subtypes. While it can become confusing at times, there certainly is a distinction to be made and you should take great care to ensure you use one or the other in your writing, but not both at once.

Giving readers whiplash by alternating between two characters POV’s too quickly. This happens all too often with omniscient narrators that are perhaps a little too eager to divulge all the character inner workings. When the narrator switches from one character’s thoughts to another’s too quickly, it can jar the reader and break the intimacy with the scene’s main character. Drama requires mystery, intrigue. If the reader knows each character’s emotions, there will be no space for drama.

Woman sitting at a table in the foreground with a man smoking in the background. Photo by cottonbro.

Here’s an example of third person omniscient that is poorly executed:

Meredith wants to go out for the night, but Christopher wants to stay home. He’s had a long day of work and just wants to relax, but she resents him for spending last night out with his friends instead of her.

If the narrator is fully omniscient, do you parse both Meredith’s and Christopher’s emotions during each back and forth?

“I don’t know,” Meredith said with a sigh. “I just thought maybe we could go out tonight.” She resented him for spending the previous evening out with his friends when he had to work yesterday as well. Was it such a crime for her to want to spend time with her partner?

“I’m sorry Mere,” Christopher said, growing tired of the nagging. “I had a long, crappy day at work, and I’m just not in the mood.” Why couldn’t she just let it go? Didn’t she realize how draining his work was? He felt annoyed that she couldn’t step outside of her own view for even a moment.

Going back and forth between multiple characters’ inner thoughts and emotions such as with the example above, can give a reader POV whiplash, especially if this pattern continued over several pages and with more than two characters.

The way many editors and writers get around the tricky-to-master third person omniscient point of view is the show the thoughts and emotions of only one character per scene (or per chapter.)

Some examples of third person omniscient done well:

In his epic series, A Song of Ice and Fire, George R.R. Martin, employs the use of “point of view characters,” or characters whom he always has full access to understanding. He will write an entire chapter from their perspective before switching to the next point of view character. For the rest of the cast, he stays out of their heads.

Gillian Shields expertly switches between her characters viewpoints by chapter and by book. In her Immortals series, the first book takes place from the first person POV when told by the main character and switches to third person omniscient when told by the supporting characters. The second book is told the same way. The third book instead is told by one of the supporting characters. The fourth book is told by another.

Leda C. Muir’s series, the Mooncallers is a fantastic example of excellent execution of third person omniscient point of view as well.

How to choose the right POV for your novel

So, now that we’ve discussed the different types of POV, examples of them executed well, and the top 2 mistakes for each type, let’s discuss how to select the best POV for your story.

Firstly, there’s no “best” or “right” point of view. All of these points of view are effective in various types of stories and there are always exceptions to these “rules.” However, it is true that some POVs are often used in certain genres and some are just better suited for certain types of stories.

First person – Most often used in YA Fiction in all subgenres, but especially in coming-of-age stories and romance. Often used in Adult romance as well. Romance stories typically alternate between main character and love interest, switching every scene or every chapter.

Second person – Most often used in nonfiction including but not limited to: cookbooks, self-help, motivational books, entrepreneurial, business, or financial books, and interactive narratives such as Choose Your Own Adventure.

Third person limited – Most often used in all fiction subgenres for all reading levels. This is the fiction go-to. The third person limited POV is fantastic for building tension because the narrators viewpoint is limited.

Third person omniscient – Most often used in high fantasy or heavy science fiction.

Of course, like I said, there’s always exceptions to the rules. If you know the rules well, then you know how to break them well.

If you’re just starting out with writing, I would suggest using either first person or third person limited point of view because they’re easier to master. However, you can always experiment with different points of view and story tenses and by practicing them, you improve your ability as a writer. Good, prolific writers learn to master different points of view because it opens their writing up to a greater audience and allows more people to feel included in their writing. Of course, we haven’t even discussed inclusivity, works by authors from a marginalized community, or sensitivity writing, but that’s topic for another day. (I’ll probably cover that in this series so keep an eye out for that.)

Whatever you chose, stay consistent.

The number one issue common to all of these different points of view is that new writers often mix them up or unintentionally alternate between multiple viewpoints within one story. As mentioned under the section covering major mistakes with third person omniscient, the other points of view can suffer from unplanned interweave of multiple viewpoints. The main takeaway here is that you should pick one and be consistent. If you do choose to alternate, consider only alternating between a handful of characters and use only third person limited or first person with each one. Whatever point of view choices you make, be consistent.

There are writers who effectively and expertly mix narrative modes because they might have multiple characters who the plot revolves around, but these kinds of switches generally don’t take place until a break in the text occurs, perhaps at a scene or chapter break.

And that’s it for my blog post on the points of view and how to identify and use them! What is your favorite POV to write in? What is your favorite POV to read in? What is your least favorite POV for both of these? What POV do you struggle with most? Let me know in the comments below and don’t forget to check out this week’s writing challenge!

Writing challenge: Your mission this week is to write for fifteen minutes while changing narrative modes as many times as possible. Post your writing practice in the comments and take some time to read the work of other writers here.

Related topics:

Book Writing 101: Coming Up With Book Ideas And What To Do With Them

Book Writing 101: How to Develop and Write Compelling, Consistent Characters

Story Binder Printables (Includes Character Sheets, Timelines, World-Building Worksheets and More!)

25 Strangely Useful Websites To Use For Research and Novel Ideas

Payton’s Picks —40+ of my favorite helpful books on writing and editing.

Check out my other Book Writing 101, and Freelancing posts.

—Payton

Book Writing 101: Coming Up With Book Ideas And What To Do With Them

Hi readers and writerly friends!

The How-To Series continues! This week, in Freelancing, we’re going to discuss how to come up with story ideas and what to do with them! This is normally where I’d direct you towards a useful, related blog post, but we’re gathering quite the list already, so I’ll just leave that bit at the end of this post for your convenience!

And now, back to your regularly scheduled programming!

So, where do book ideas come from?

Book ideas can come from anywhere. That’s it. Blog post over. We can all pack up and go home. Right?

Well, yes, book ideas can come from practically anywhere, but it takes more than just a juicy theme or a compelling character to make a book. You certainly need those elements present to make a thrilling novel, to be sure, but its so much more than that. However, we’re not here to discuss the elements of a novel —no, we did that last week. (Check the links below!)

While novel ideas can come from just about and where and anything, you can also brainstorm novel ideas. Think about your favorite novels and see how you can create a mashup of two or more stories that would fit well together and put your own twist on it, such as Alexa Donne’s Jane Eyre in Space —Brightly Burning, or Pride and Prejudice and Zombies by Jane Austen and Seth Grahame-Smith, (the same writer who did Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter!) for example. While the latter is a literal mash-up, the former is more like a mash-up or genre-bender with Donne’s own twist on the original premise.

So, think about how you can put your own spin on your favorite tales!

How would x-story be different if it were…

set in space? in the center of the Earth? on another planet?

told in another genre?

told from the opposite gender or a non-binary narrator?

told from someone with 30-years age difference?

told from the perspective of an animal?

mashed-up with your favorite movie?

told from a different POV or story tense?

Write the book YOU want to read

These are just a few ways to put a refreshing spin on old stories to make them feel new. You can also consider what kind of book YOU want to read. How would your favorite story be better? How could you change it to include certain elements you feel it is lacking, but with a whole new cast of characters, a new theme, and a fresh new setting? How can you rework and existing story to include more representation for a minority?

Explore fun websites to spark inspiration

I have an interesting little blog post that does just this! (It’s listed at the end of the blog post too!) Essentially this post is a long, organized list of fun websites that you can read or interact with to spark inspiration for your next book. If you already know what you might like to write about, try some of these sites out to see how you can put a new spin on it to make it your own story that has never been told before. For instance, I might like to try rewriting Hush, Hush, but instead of the typical plot points that occur throughout that story, I might swap the genders of the characters, and set it in 1943, where an asteroid shower has been happening for the last 30 years. See how that immediately changes the whole story? It might not be the best example, but you get the idea! Consider reading articles on news sites from Buzzfeed to the New York Times to get inspiration from the crazy every-day lives of other people, like Florida Man. Sometimes, the truth can be stranger than fiction and can spark even the most outrageous novel ideas that eventually become great stories!

Read bad books!

Ever heard of BookTube? Well, if not, then bless you! It’s what book YouTubers and others in the community like to call the little corner of the video-streaming service that is dedicated to all things bookish!

Consider looking up scathing reviews of books you may or may not have heard of and see how you can rewrite them to succeed in the areas they failed. Obviously, none of this advice is suggesting you plagiarize, by any means. However, it is okay to take an overly broad and vague story premise, mold it, and make it your own. How can you turn this book that is absolutely loathed by the Bookish Community into a novel that readers everywhere will love simply by reimagining the things they went wrong with? For instance, there are plentiful mixed (and mostly critical) reviews for Sasha Alsberg and Lindsay Cummings Zenith.

Here is the description from Goodreads.com:

Most know Androma Racella as the Bloody Baroness, a powerful mercenary whose reign of terror stretches across the Mirabel Galaxy. To those aboard her glass starship, Marauder, however, she's just Andi, their friend and fearless leader.

But when a routine mission goes awry, the Marauder's all-girl crew is tested as they find themselves in a treacherous situation and at the mercy of a sadistic bounty hunter from Andi's past.

Meanwhile, across the galaxy, a ruthless ruler waits in the shadows of the planet Xen Ptera, biding her time to exact revenge for the destruction of her people. The pieces of her deadly plan are about to fall into place, unleashing a plot that will tear Mirabel in two.

Andi and her crew embark on a dangerous, soul-testing journey that could restore order to their ship or just as easily start a war that will devour worlds. As the Marauder hurtles toward the unknown, and Mirabel hangs in the balance, the only certainty is that in a galaxy run on lies and illusion, no one can be trusted.

—Sasha Alsberg and Lindsay Cummings, Zenith

This book has a 3.11 average rating and is most known for its unconvincing worldbuilding, lack of original vocabulary explanation (the author drops in made-up words without explaining what they mean beforehand and leave the reader to remain confused, since there is a lack of a glossary in the book as well?) sci-fi elements that simply don’t make sense —such as impenetrable glass spaceships (with metal defense covers?) and golden, double-trigger revolvers— characters that are lazily thrown together and also do not make sense, poor-quality writing, overwhelming number of clichés present throughout, and—I’ll save you the rest because I could go on and on. The point is that this novel was incredibly overhyped, and fans of Alsberg’s YouTube videos were sorely disappointed when the book did not deliver.

So, as a writer, how could rework this story to succeed where it failed? How can you take extra time and immense care to ensure your characters are compelling and are actively evolving throughout the story? What kind of research can you do to verify that your story keeps in line with traditional sci-fi elements, while managing come across in a refreshing, interesting, and new way? How can you make sure your readers thoroughly understand the vocabulary and systems present in your book? What do you personally wish had been done differently? These are the types of questions you have to consider when brainstorming, because if you think you have the skill to rework a very poorly received influencer novel such as Zenith, then you just might have a story idea on your hands. I would suggest reading books that have overwhelmingly terrible reviews and seeing if you can distill the poor, unfinished, low-quality work into something fresh and new that you too would want to read. You can also do this with movies, TV shows, plays, music, and any other art form that leaves you feeling underwhelmed or unsatisfied once you’ve finished consuming it.

One fantastic example of a writer who reworked a story they were unsatisfied with is Claudia Grey’s Defy the Stars which she wrote after seeing the movie Prometheus and being dissatisfied with how the movie’s producers portrayed David 8. She was inspired to rework the story and write her own book about an android the way she wished it had been told.

In an interview for Nerdophiles on Twitter, Grey explained how she got the inspiration for Defy the Stars from Prometheus:

How did you come up with the idea of writing Defy the Stars?

You know, the actual genesis of this story came a few years ago when Prometheus came out. A lot of it had to do with Michael Fassbender’s performance as David 8. He just walked right into the uncanny valley and stayed there and it was great.

One area the movie didn’t really explore much but that was really interesting was the fact that Elizabeth Shaw was trying to really evaluate how much of David is machine. It’s this very tiny thing but I thought that was a really interesting thing they should have played with more. They have this person who has this other mission – her job is not to analyze this guy – but who spends time trying to figure out if she’s working with a machine or if she’s working with somebody. And that’s not going to be a question that has a really solid answer.

That idea then took root and became the idea of Defy the Stars.

—Claudia Grey, Nerdophiles

Read more from this article in the link below!

Another great example of a story premise that was reworked is “Errant” by Diana Peterfreund.

As per Goodreads.com:

In 18th century France, a noble family prepares to celebrate their daughter's arranged marriage by holding a traditional unicorn hunt. But when an unusual nun arrives at the chateau with her beloved pet to help the rich girl train, nothing goes as expected. Starring hunters, fine ladies, fancy frocks, and killer unicorns.

—Diana Peterfreund, Errant (Killer Unicorns #0.5)

This short story is not only a historical reimagining of arranged marriages with never-before-seen traditions, but it’s also a fantasy. With KILLER UNICORNS. It’s exquisite.

Don’t be afraid to look to other media where narratives left you feeling dissatisfied and consider how you can tell them in a new way that succeeds where these stories failed. And on the flip side, look at where your favorites succeeded and consider how you can channel that into your story idea.

Take inspiration from your own hobbies and interests

Are you a gamer? Consider writing yourself into the world of your favorite video game and then change it to make it your own. Are you a chef? Consider how you can reimagine cook-books to find balance between overly chatty blog posts and old-school recipe-only cook books that lacked that certain something something. What kind of morbid curiosities can you dive deeper into to pull a story from? I personally have a morbid curiosity with true crime and sinkholes even though they both creep me out. Maybe I could write a thriller about people adventuring into the world’s deepest sinkhole only for the trip to go awry and lead to murder, mayhem, and mystery as the characters grow increasingly desperate to survive being trapped inside the belly of the earth?

Yeah, no I wouldn’t write that. Not ever. Not even if you paid me. Sinkholes and caves are the worst!

But you could! You could write about LITERALLY ANYTHING.

What weird thing are you obsessed with? Can you turn it into an interesting, new, dark, fantasy? How can you weave that topic into a novel?

Examine events and people form history to spark inspiration

What is your favorite time period to study? I personally love the Revolutionary war and the romantic period in literature. What chunk of history fascinates you? (Leave a comment below!) How can you take your favorite elements of that time period and either modernize them or convert them from history to fantasy?

Subscribe to writing prompt websites and social media pages

There are TONS of writing prompt profiles on Twitter, Tumblr, and Instagram and not to mention the plethora of other websites on the world wide web. You can find story ideas on reddit or on Wattpad too! I personally am subscribed to @redditvoice, @reddit, @mr.reddit and @writing.prompt.s on Instagram and I am signed up to receive daily writing prompts from Storyaday.org (they also have a great list of where to find story prompts). Likewise, you can purchase writing prompt books or even play around on your favorite meme sites to spark inspiration. You can also take inspiration from fanfiction as well!

Those are just a few ways to come up with ideas, but they can truly come from anywhere. The truth is, the more media you consume and the more life experiences you have, the more avenues you have open for story ideas to just waltz into your life. Watch some movies, read a few books, go out and catch a local play and then sit down for a good ole brainstorming session and see what you can come up with.

How to keep your story ideas once you’ve been inspired

MS Word document with New Story Ideas. Alternatively, you can use Pages or Google Docs. Photo by Payton Hayes.

Just like with writing, there’s a ton of different methods of jotting down your story ideas. You can keep them in a notebook or binder. You can make an ongoing Google Doc or Microsoft Word Document. You can store them in Scrivener or Evernote. It really doesn’t matter what you use. Just make sure you keep them organized and include enough information so when you come back to them, you remember your ideas vividly and know where to pick them back up. I prefer to keep my fleeting ideas in a single Microsoft Word document titled “New Story Ideas” where everything is in a bulleted list.

Sometimes, the ideas a fully fleshed out while others are simply one-liners because that’s all I could think of when I was writing it down for later. Figure out what works for you and keep it in an easy to reach place so you can access it whenever the creative spirit strikes you! If you can try to write a brief synopsis for your book ideas so you can come back to them and know exactly what you were talking about 1, 2 or 5 years later. Additionally, don’t be afraid to let your story ideas ferment within that list and feel free to add to them over time when you get more inspiration for them.

And that’s it for my blog post on how to come up with story ideas and how to keep them once you’ve gotten them! Brainstorming is such a personal process and can be different for every writer. How do you come up with ideas? Let me know in the comments below and don’t forget to check back next Friday with another installment of this Book Writing 101 Series! Part 4 will be out next week!

Related topics:

Book Writing 101 - How To Chose The Right POV For Your Novel

Book Writing 101: How to Develop and Write Compelling, Consistent Characters

Book Writing 101: Everything You Need To Know About Dialogue

Story Binder Printables (Includes Character Sheets, Timelines, World-Building Worksheets and More!)

Payton’s Picks —40+ of my favorite helpful books on writing and editing.

25 Strangely Useful Websites To Use For Research and Novel Ideas

Kiss Me Deadly: 13 Tales of Paranormal Love (Errant by Diana Peterfreund)

See all posts in Freelancing. See all posts in Book Writing 101.

Thumbnail photo by Jason Goodman.

—Payton

When Writing Becomes Difficult

I get it—trust me. I just came back from a writing hiatus and while I wish I didn’t take that time away from writing, it’s hard to picture me where I am now without it. So, as we get into it, let’s think of this as a group therapy session.

Hi readers and writerly friends!

This week in Freelancing, we’re discussing a little something that hit close to home for me and that’s when writing becomes difficult. Writing is hard. Full stop.

I get it—trust me. I just came back from a writing hiatus and while I wish I didn’t take that time away from writing, it’s hard to picture me where I am now without it. So, as we get into it, let’s think of this as a group therapy session.

Deep breath in and out. It’s going to be okay.

Now, let’s do this.

Woman covering her face with her hands. Photo by Anthony Tran.

Writing is hard. No matter how many times I say it, it doesn’t make the process any easier. Writing can be really, really, reeeeeally difficult sometimes. Most of the time, in fact. It’s a process that makes you swoon, cry, cringe, hyperventilate, and want to tear your hair out at every turn. It’s frustrating when you want to write but you just don’t feel motivated or inspired enough to do so. It’s frustrating when you feel motivated and inspired but you just don’t feel like writing. It’s frustrating when you don’t want to write but you have internal and external pressures on yourself that make you feel like you should be writing when you’re not, and that doesn’t feel good either.

And even if you managed to get past those hurdles, writing can be hard for a plethora of other reasons as well. It’s frustrating when the words just aren’t working on the page, or when you just can’t seem to iron out the kinks in your plot so that it makes sense.

I’m raising my hand here.

Writing is not an easy feat and it’s not supposed to be. Writing is a trial. It requires bravery and vulnerability, and a willingness to be consistent. It feels incredibly gross sometimes—like when you know you need to just sit down and crank out that first draft, but you keep self-editing your previous passages out of fear of inadequacy.